The Human Condition in Marble

An interview with Hilde Van Canneyt

100 Expo

2014

Hilde Van Canneyt: Hello Athar, you were born in Rome, but grew up in Florence. Influenced by the beauty of the better art gods, you soon began to sketch their world-famous sculptures.

Athar Jaber: It was my favorite pastime. Our house in Florence is 100 meters from the Accademia Gallery, where Michelangelo’s David and the Slaves are exhibited. Every spare moment I had, I went to the museum to observe and draw them. I was there almost every day. But when the queue at the entrance was too long, I went downtown to study the countless statues that decorate the city. This gradually led to my love for sculpture. Not self-evident as my family consists entirely of painters. I started making sculptures relatively late.

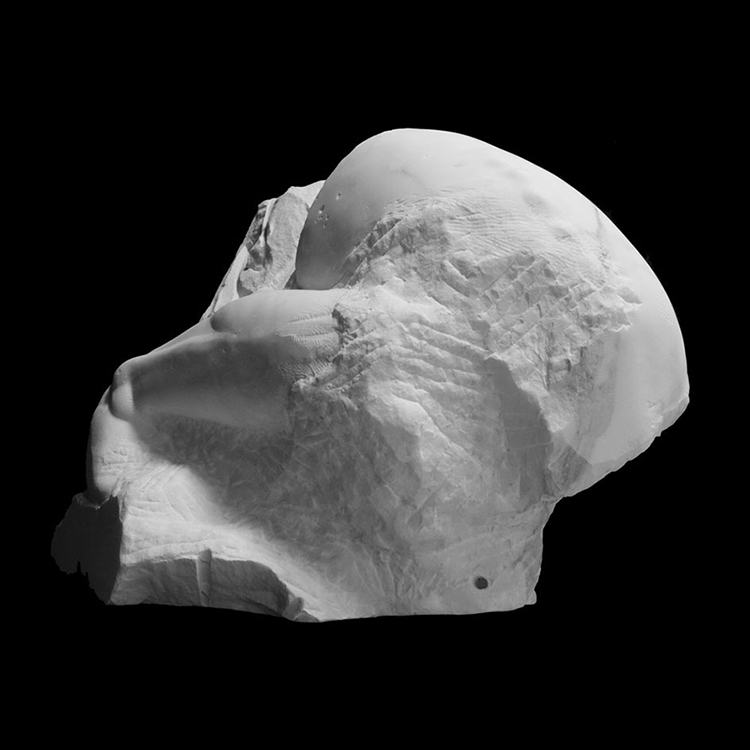

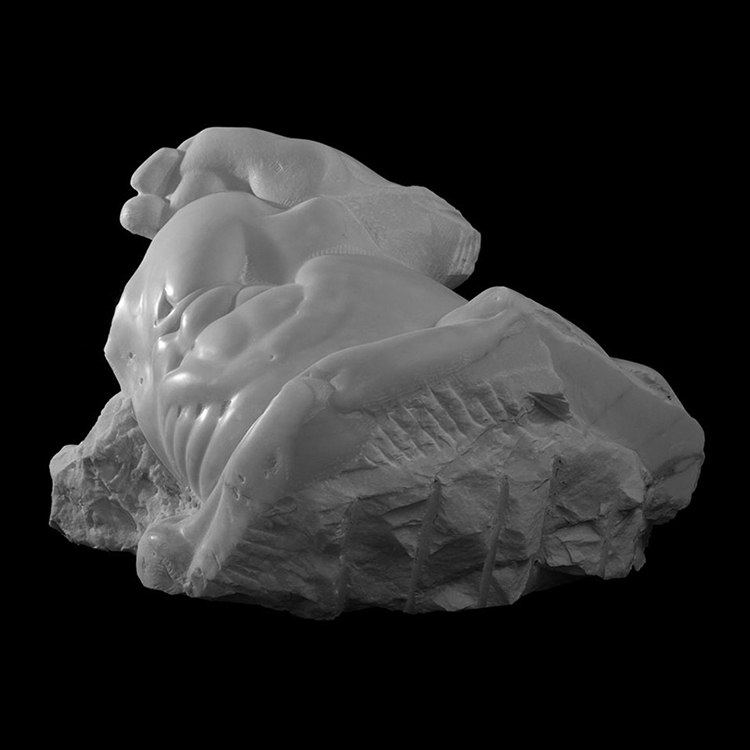

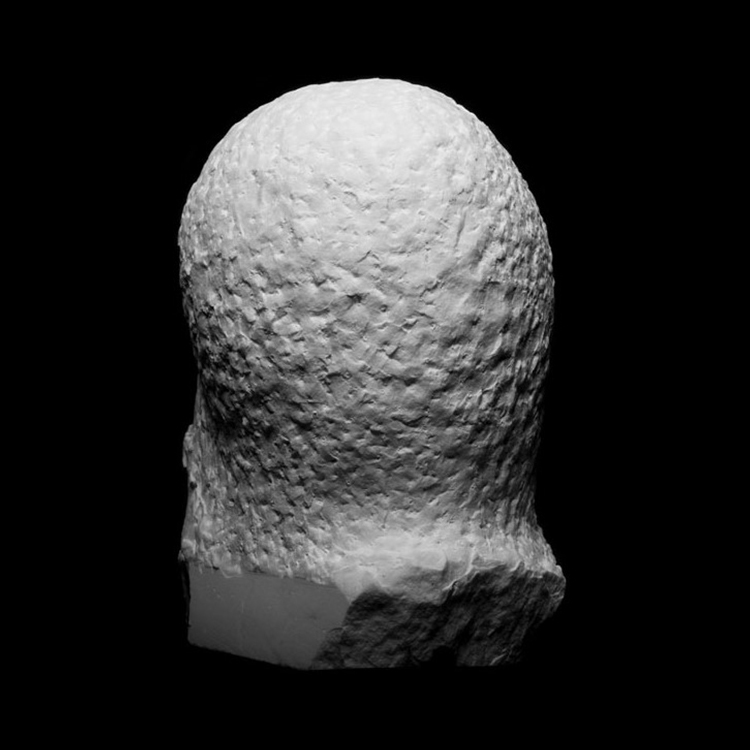

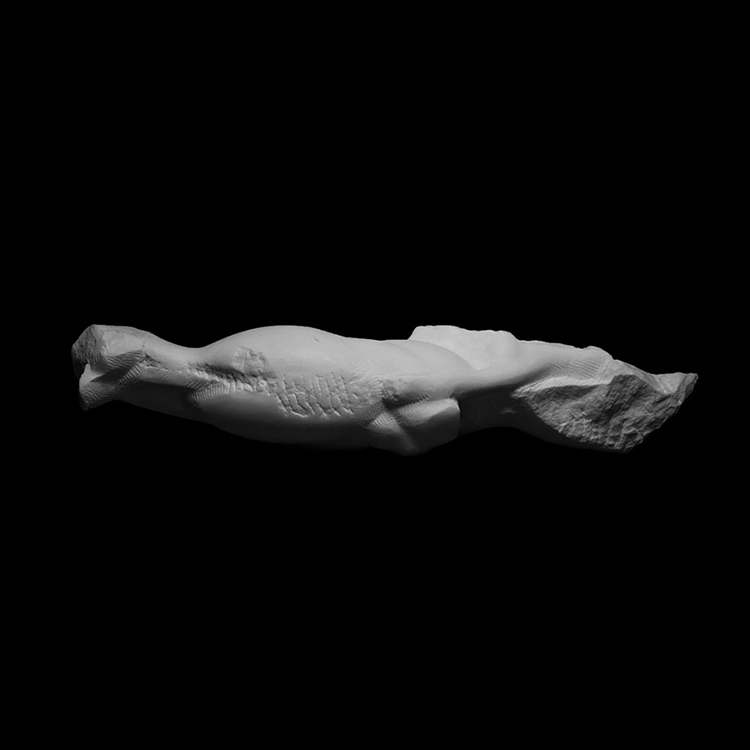

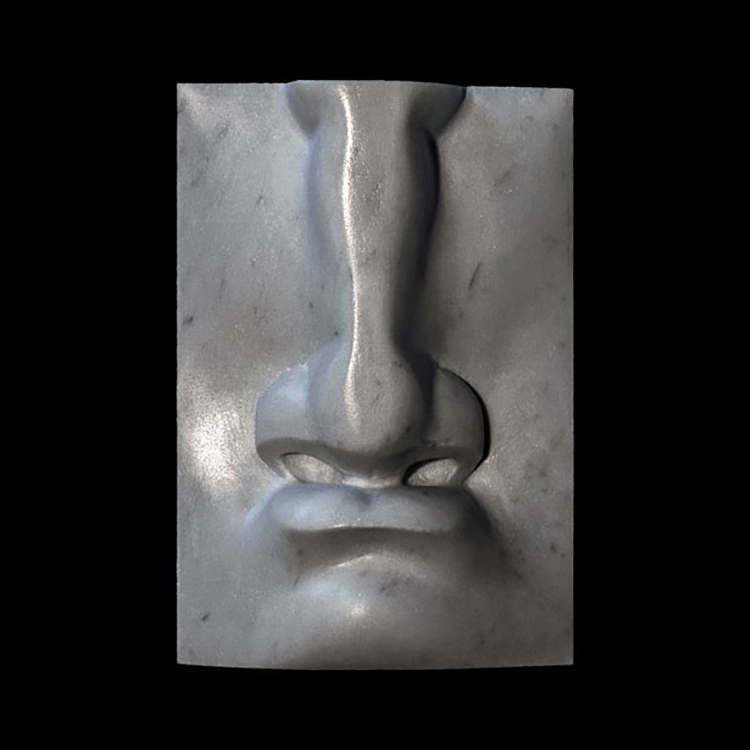

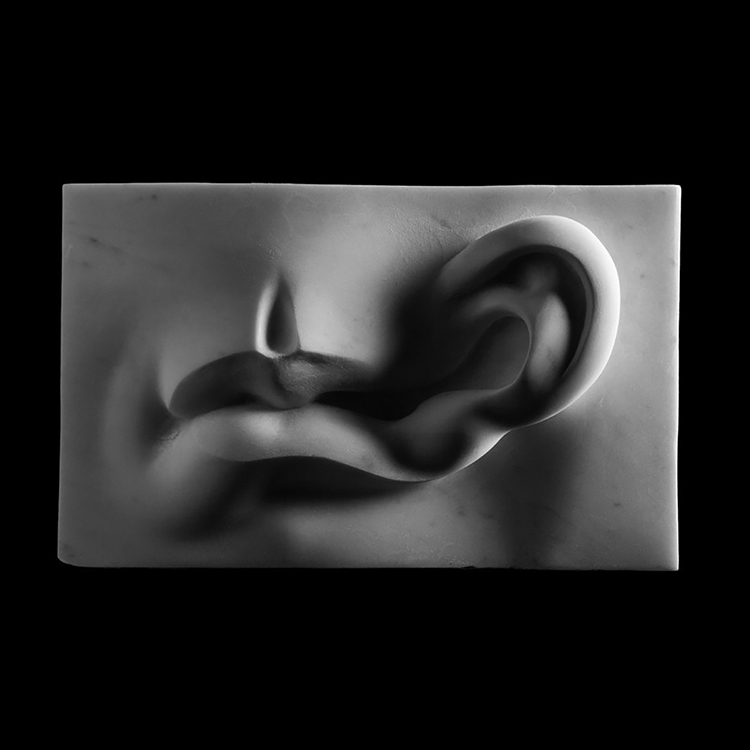

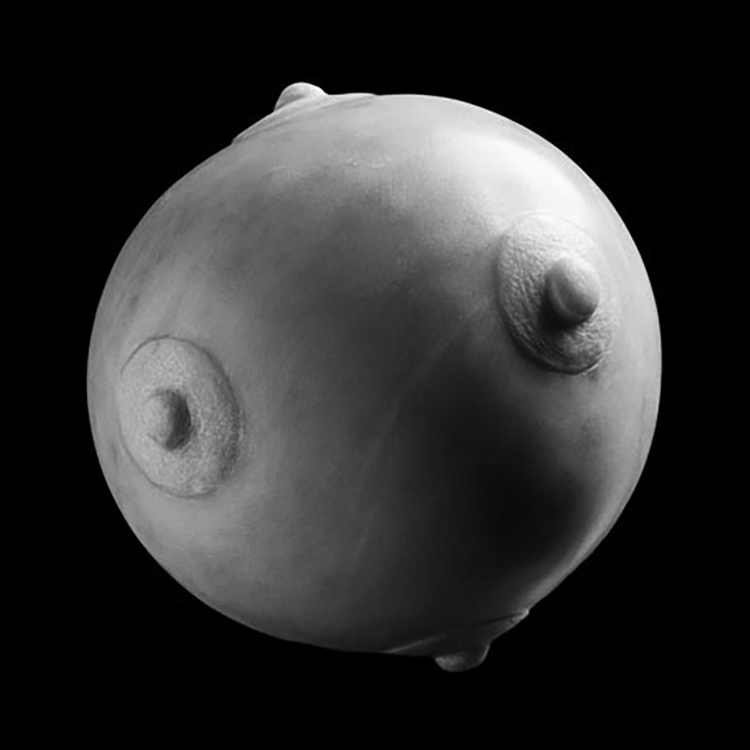

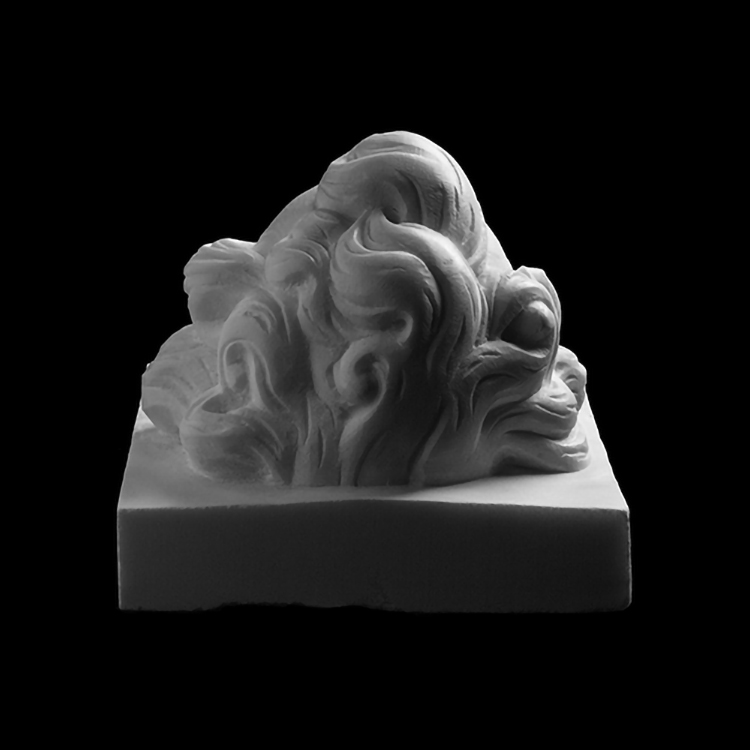

HVC: In 2004 you decided to study at the Royal Academy of Antwerp. You graduated with a more than life-size sculpture of 500 kilos made of Carrara marble. This was the starting shot for your Opus 4 series, which ultimately consists of four sculptures. We see realistic / classicist elaborated naked body parts in a twist dance with the raw Carrara marble. You describe it as an inspiration fusion between Michelangelo and Francis Bacon.

AJ: The hours I spent at the Galleria dell’Accademia had a big impact. When I started the series, I wanted to make a contemporary version of Michelangelo’s slaves. The theme is timeless: the mind trapped in a body. But, depending on the zeitgeist, this duality can refer to other relationships: the individual is trapped in a society where laws and rules apply that are alien to his own nature, he is subject to inescapable violence. The reference to Michelangelo and Bacon is flattering, but easy, maybe too easy. Because the first thing that strikes you is that for both artists the body is the expression of these ideas. But they are not the only ones who depict these ideas and we need not limit ourselves to the visual arts: they can also be expressed by dissonances or unresolved cadences in music, ruins of buildings or cities, what remains of a body after an attack…

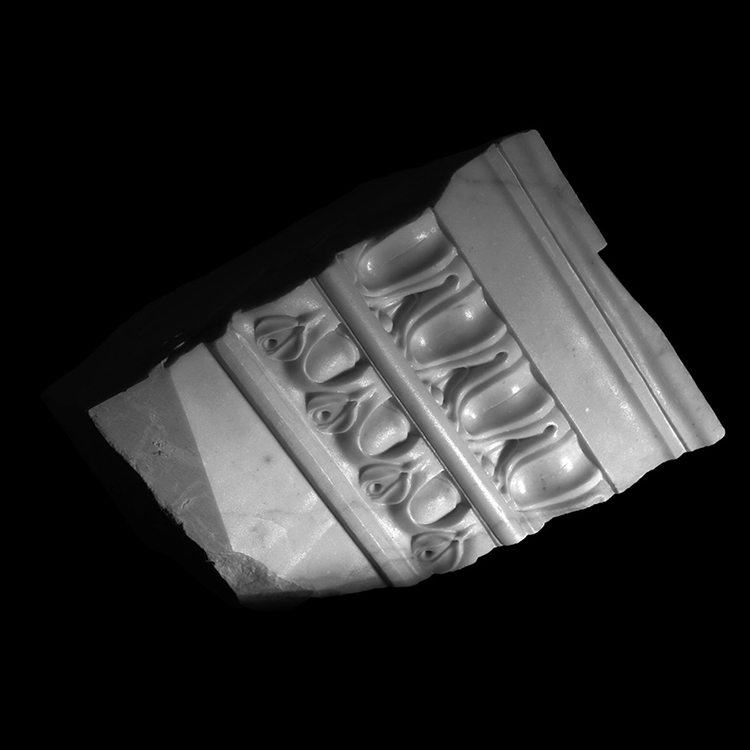

HVC: You also want to consciously update the tradition of marble cutting, which has not played such a role in recent years. The perfect finishing and sanding of the marble, for example, is also something that is no longer so important in contemporary art.

AJ: On the contrary, you see nowadays that finishing marble statues is taking on maniacal proportions. The images are seldom made by the artists themselves, who know little about this. This is outsourced to specialized firms that often work with the help of modern technologies. There is nothing wrong with this, except that the work is aimed at an end product and is no longer looked at in the intermediate phases, no possible alternatives are considered. Contemporary marble statues today have more in common with industrial design than with sculpture. I believe that with the emergence of new technological developments in 3D drawing and printing, sculpture is in a phase similar to the situation that painting faced when photography was on the rise. Precisely because of these developments, I consider carving the sculptures myself to be a conceptual choice that should not be underestimated, almost performative in nature.

HVC: You make one image per year. Belgian sculptor Heirbaut can only make one or two a year. What wood should sculptors like you be cut from?

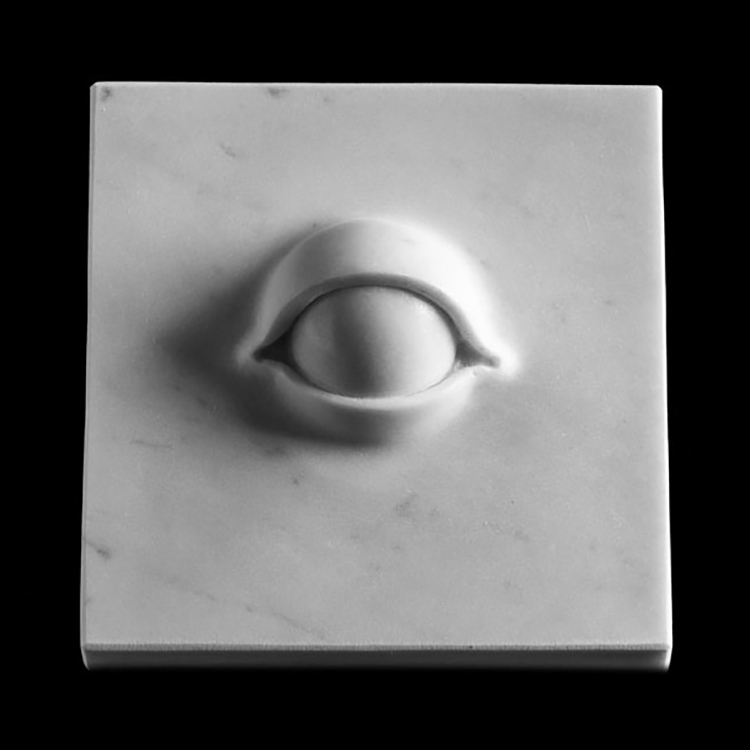

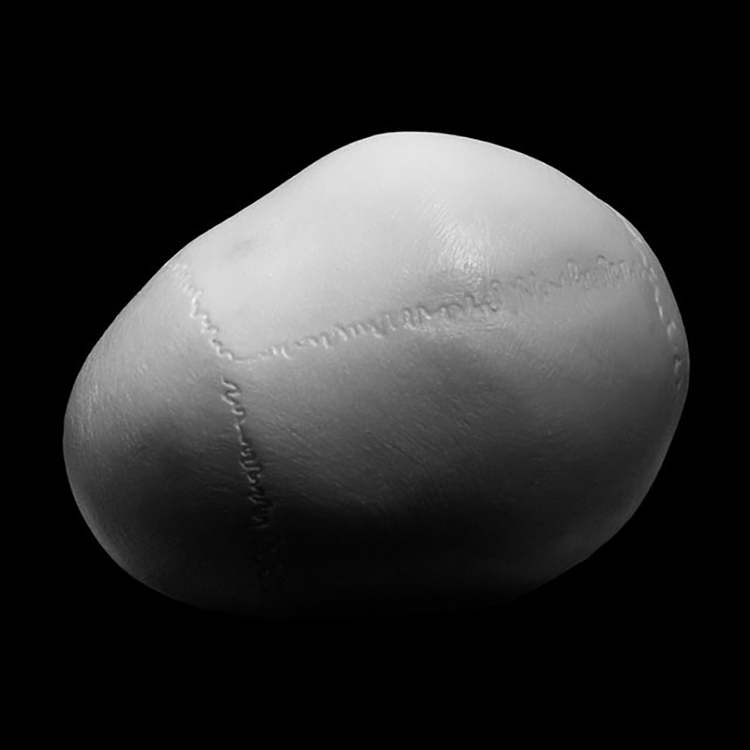

AJ: Making a statue yourself in stone takes a long time. Specific to the direct carving, is the method of working directly in stone. Much of the time is spent looking at the piece. This is to make choices with regard to, for example, the general composition, the lines and the light projection. And of course, without losing sight of the content of the work. These choices are very personal and ultimately determine the individuality of a sculptor. Frans Heirbaut was my teacher, and I owe much of what I know and know about sculpting to him. An absolute requirement to practice our profession is a lot of patience. But mainly love for the profession. You could say that I am addicted to cutting: I enjoy striking with a hammer and chisel on a block of stone, the vibrations that run to the arms, the pieces of stone that shoot off all over the room, the rhythm, the sound, the dust … It is an intense experience to do this for hours. Regardless of the result, it doesn’t even have to be there. I am currently working on a series of works that emphasize this aspect of the mere working of a stone

HVC: I am not very comfortable with it, but looking for such a block of marble to cut in, how does that work? Do you go there or go to Carrara yourself?

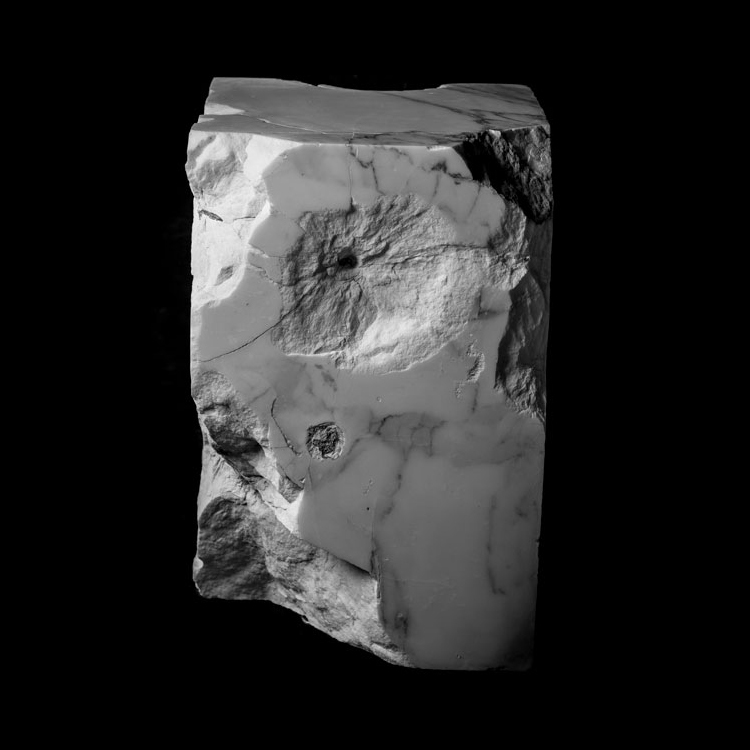

AJ: Before my first block – I was still a student – I first worked as a waiter for a summer to save money. Then I went to Carrara to find a block of marble that was within my budget. It was a long search, about a week, in the mountains, the quarries, the sawmills. In the end, I almost instinctively chose a beautiful statuario marble that was somewhere on the side, far from the other stacked blocks. It was relatively cheap because it had a large crack, which divided the block into two irregular pieces. At the time I had no idea what I was going to make of it. Ultimately this resulted in the first two images of Opus 4. As with all things, your budget dictates a lot: if you can afford it, go to the quarries to pick a piece of marble straight from the mountain. I don’t have this luxury, but I don’t think it’s that important either. I like to accept limitations and make something with them. In the grooves there are often already cut pieces stacked, ready to be sold. From this I choose the block that appeals to me the most. You look at the quality of the crystals, the color of the marble and whether there are cracks or “hairs” – small sheds. Usually there is also an incomprehensible attraction to a certain block. Call it love at first sight if you want…

HVC: What is your main work material? Do you just go to your studio, as if it were nothing, or do you have to give yourself some courage? Do you have a fixed schedule before you go to your studio or before you start working? I can imagine that you cannot leave so much to chance …

AJ: Again, I have to contradict you: coincidence is very important. I never work with a clear idea of what I want to get out of the block. Usually I start with one piece and the rest will follow by itself. Compare it with a free jazz improvisation. It is an art of responding to coincidences and being open to giving them the space to develop new insights. There are of course also times when I don’t do much for months because I don’t “see” it. A period when my brain must familiarize itself with an aesthetic that I had not foreseen. And so, you keep surprising yourself and growing, both personally and as a sculptor. It is precisely because of the improvising nature of this practice that my state of mind is very important: a book I am reading, a film I saw the night before, the news I read in the newspaper, a conversation, the weather, a hangover … Anything can make a difference to certain choices I make while carving. But this is also true of other aspects of everyday life.

HVC: Do you work alone, or do you have assistants? And do you prefer to work in silence, or can you have some tunes?

AJ: Since I improvise on the stone myself, I can’t use the help of assistants. Every mark I make could be the last one. In that sense the picture is always finished. I have a fascination for unfinished works: Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge, Gogol’s Dead Souls, Orson Welles films, … There is also a fatalistic idea behind this … In addition, the presence of a person limits my freedom. While this is inevitable in everyday life, in my studio I can bend reality to my will and that is why I prefer to work alone. Music, on the other hand, is a very important element that I use as an amplifier of my activity: if I have to do exploratory or intensive work, I like to have something unknown or contemporary, while in the quiet finishing phase, I like to be accompanied by trusted friends: Bach or Beethoven are often welcome.

HVC: Leonardo da Vinci said in 1519: “If mind and hand don’t go together, no art is created.”

AJ: In Leonardo da Vinci’s day there were lively discussions about what art should or should not be and how to make it. They were different times from ours and I dare not compare them or make absolutist statements that rule out other possibilities. If there is one thing the arts teach us, it is that anything is possible.

HVC: By the way, what is your best moment between the idea in your head and the finished sculpture? The moment when you think: “That’s what I’m doing it for.”

AJ: When I make mistakes… then there is a moment when I feel uncomfortable because something didn’t go to plan. A moment of crisis. A solution must be found for this. Often you have to think outside the box to see this error no longer as such, but as an opportunity to develop new ideas. This is a process that can sometimes take months. It is an exploration of the image, but rather of yourself. Finding a solution to these “luxury problems” is an enlightening, almost ecstatic experience. Because you achieve a result that you never imagined. You transcend yourself.

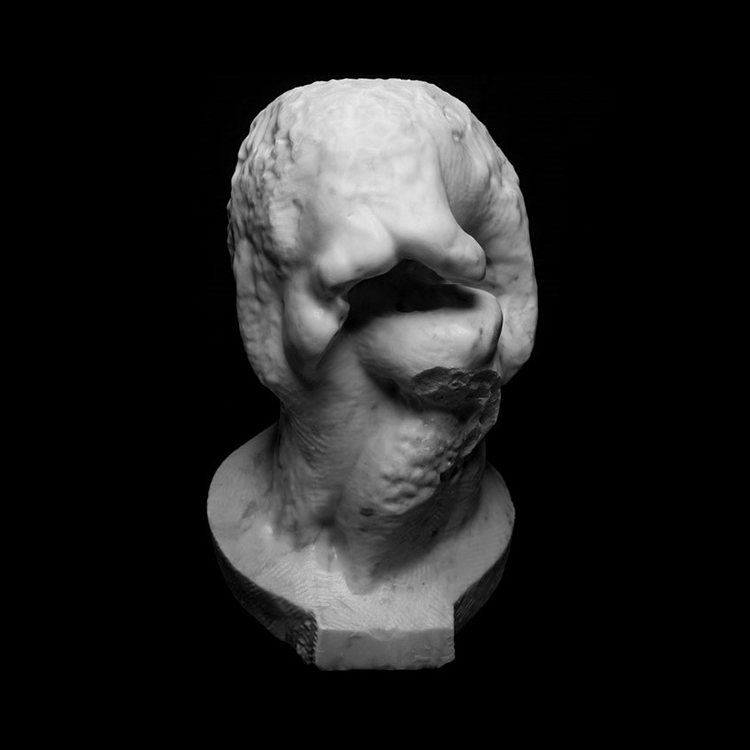

HVC: Besides your Opus 4 series, I also saw three realistic white heads hanging next to each other on your website. The middle head is a man with a beard. I can’t put my finger on it: are they philosophers or…?

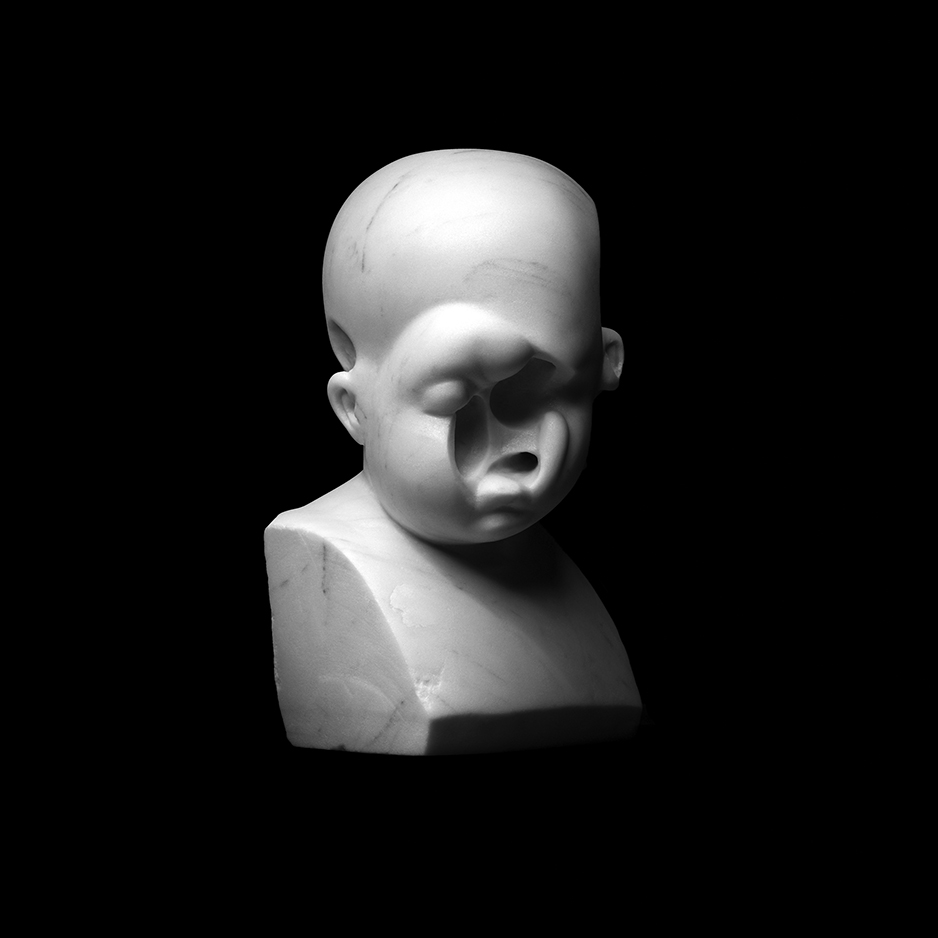

AJ: It’s family: my dad and two uncles. Romans used to place busts of family members at the entrance of their home as a reminder of their genealogy, their origins and to remember their past. I don’t want to limit this genealogy to family members, but to extend it to people who have played an important role in shaping who I am today, including friends and teachers. The heads you’ve seen are just sketches for a series of portraits I’m working on right now. The final series will consist of a dozen marble portraits, albeit deformed and modified like the Opus 4 series; a resemblance to the original model will not be the priority. After working with the body for five years, I now want to do something different and then go back to the body. I already have plans that can safely fill the next ten years. Portraiture, a discipline that occupies an important position in art history, seems interesting to me to investigate and interesting to make my own interpretation of it.

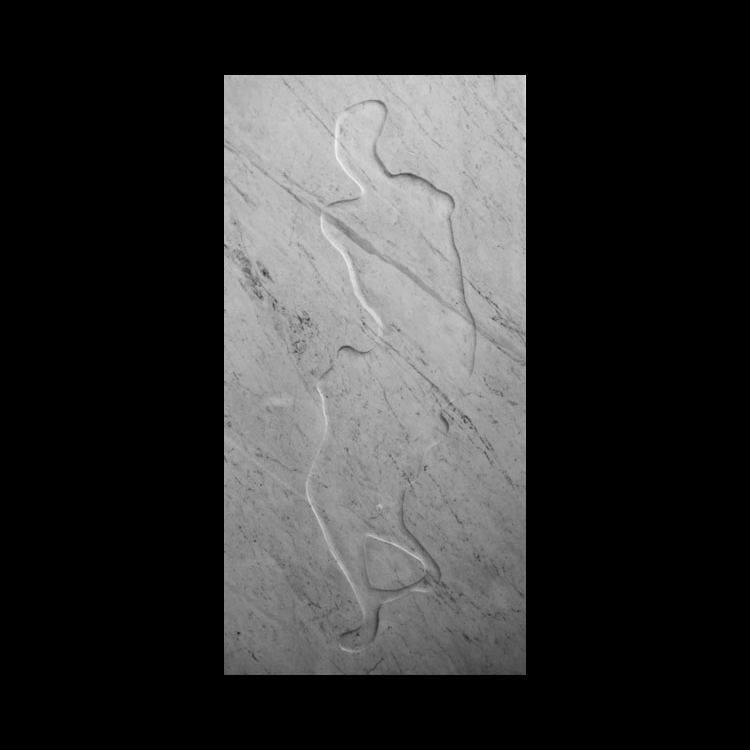

HVC: On your website we also see pen drawings, made between 2008 and 2012. They remind me of the drawings of Rafaël, Dürer and “our” George Minne. Do you see an evolution in your drawing over the years?

AJ: Drawing is a language in itself. The more this is practiced, the easier one feels about it. Our existence is marked by a different type of language: “In the beginning was the Word …”. I am not a believer, but we live in a society that has its roots in these verses and that says a lot about our nature, whether religious or not. Our communication is mainly done through words. Even when we are alone, there is a constant stream of words in our brain. But for certain disciplines, such as visual art and music, there is a different language. I also think more in terms of images: when I see something, I save it, in my memory but also in a folder that I hope to publish one day. I use it to make a visual and substantive connection with the other thousands of stored images. That connection sometimes seems far-fetched but remains very clear to me and I have no need to clarify this in words. Unfortunately, it must be done in order to speak to a wider audience. I know it sounds elitist. One of the greatest efforts I must make while teaching is the translation from visual to spoken language. Speaking is a difficult task for me anyway, perhaps because I have never lived in a country long enough to develop and master a perfect sense of language. Here is where drawing takes an important position: for me it is a mindset where I feel more comfortable than thinking with words.

My drawings were much more defined at first than they are now. Then everything had to be clear. Perhaps more out of necessity for myself to determine what I wanted to express. Now that precise determination is no longer necessary. I notice that I am becoming much freer. On the one hand I trust my hand more and allow myself to be surprised by the lines it makes on paper and on the other hand I can better direct these surprises towards the result I want to achieve. I don’t have to finish everything either. And this has its consequences on my images, which are less and less finished. When I think I’ve been able to capture the essence of an image, I stop. Everything else is an afterthought, decoration, and therefore not necessary. Still, I have to admit that I’m not satisfied with the drawings I’m making for the portrait series. I’m still looking. That is why you can only find drawings until 2012 and no further. I make hundreds of drawings a year, but after a rigorous selection, very few remain.

HVC: Your drawings do not serve as a preliminary study – you start directly in the stone. Do you see them as independent (art) works? You also sign them with a stamp, why that idea?

AJ: They are more studies of a certain theme, feeling, a certain atmosphere. They cannot be literally translated into stone. That is impossible and uninteresting. The whole search in stone would be lost. I draw in the evening and at night, as processing of certain problems that I encountered in the stone statues during the day. They are also improvisations, but on paper, to support the cutting process. It is impossible to work day and night in the studio, even physically, but it is important to stay in a certain train of thought, also outside the studio. Drawing makes this possible. For these reasons, I personally don’t see them as independent works, but the public does …

On the one hand, the stamp appears as an alternative to fetishism a signature. The whole drawing is a signature in itself, I do not understand the need to add my own name in handwriting underneath. If I have to, for the market, I prefer a neutral stamp. It is also a nod to the stamps that can often be seen in old master drawings of certain collections: a strange element that fascinates me.

HVC: What is your relationship modeling versus cutting in stone?

AJ: I don’t like to model clay. It’s too soft, shapeless, almost characterless. You can make anything with it, it offers no resistance. For some, this is precisely the quality of clay, and I am convinced it can be. But I don’t like that. Against this, stone also has a broader sculptural and cultural legacy that I like to refer to.

HVC: Is painting for you?

AJ: My family consists mostly of painters. When I was a kid, I was surrounded by people who did it on a professional level: my mom, my dad, two uncles and all their friends. Painting seemed natural to me and I often did it as a game. Over time, I became more attracted to sculpture, perhaps precisely because painting was so common. Now that I can think about it rationally, I am intrigued by the greater connection to reality that sculpture has over painting. Sculptures take up a place in space and as a result take that away from us: our body is confronted with this. See it as a restriction on our freedom, a threat that we take into account. Where there used to be nothing there is now something we have to walk around. In that sense, making and showing an image is a violent action, separate from what is depicted and its usefulness. Sculptures therefore have a concrete impact on our physical reality, they are part of it.

HVC: Do you have accommodation at a gallery? Seems difficult, because in addition to bringing good art, their main goal is usually to sell art. But your work is not made and sold like hot cakes, I suspect.

AJ: I work in a traditional way, with as little use of power tools as possible and completely without the help of pneumatic tools. It’s a slow, time consuming, intensive process. As a result, the price of the sculptures is relatively high and the production low: on average, I make one sculpture a year. Due to these circumstances, I have not yet come across a gallery willing to support me in this process. That is why I often exhibit outside the commercial sector: more in a private circle, at someone’s home, or at associations and cultural institutions, such as at the moment in the Academia Belgica in Rome. Teaching at the academy of Antwerp allows me to maintain this luxury position without compromising my work.

HVC: Can you tell us something about your latest exhibition “Terrible beauty” in the green marble hall of the Academia Belgica in Rome? Have you chosen the title yourself?

AJ: It is a nice coincidence that “Terribile Bellezza”, the Italian title of the exhibition, runs almost simultaneously with the Italian film “La Grande Bellezza”, which also has Rome as a background. The title was chosen by art historian Johan Pas for the text he devised especially for this exhibition. I only made the link with the film in Rome and have not yet been able to ask him whether that was done on purpose.

For me this is an important exhibition. It’s the first in Italy, and then also in my hometown. A return to the origins. Many of the statues I refer to are preserved in this city. The statue on display there (Opus 4 No. 2), for example, is partly inspired by “The Dying Gaul” which is in the Capitoline Museums and the “Torso belvedere” in the Vatican Museums. The perception of a work changes drastically depending on where it is presented. In Rome, marble statues and ruins are part of everyday reality and such an image is viewed and experienced differently than, for example, here in Belgium. For example, nobody in Rome thinks it’s so special that I work in marble. It may be necessary to ignore this sensational aspect, so that the essence of the image can come into its own.

HVC: Do you have a plan B for when you could no longer cut the stone?

AJ: I often think about that: “What if something happens that prevents me from cutting?” But it’s an equally fatalistic question like “What if I die tomorrow?” We’ll see then…

HVC: If you could travel back in time, to which art or time period would you like to return? (Can we guess the answer?)

AJ: Why would I want to go back in time? Every era has its beauty and misery. The challenge remains to process these properties and turn them into something. Regardless of the period. I believe we can develop our potential qualities much better in our time. There may be more competition, but also a lot more knowledge. It is important not to think in the short term and not lose sight of the larger context. We all have limitations; there is no point in ignoring or denying them. In order to deal with that, we must first accept them. Having said this, to avoid any misunderstanding, let me make it clear that I am a pessimist.

HVC: Could you, as in the past, make a sculpture on commission?

AJ: Yes. As long as the client trusts me and gives me the freedom to realize my interpretation. Coincidentally, I am currently working on a small assignment in which I was given carte blanche in all respects. Only a number of thematic guidelines are indicated. Commissioned work is not something of the past alone. Many commissioned works are still being done. New opera or theater productions, public buildings, monuments and more. There is nothing wrong with this, on the contrary, but it is important that a situation is created in which the requested artist can maintain his or her integrity.

HVC: What is the social relevance of your work?

AJ: It is not in the sense of world improvement or a plea for certain political beliefs. For me art should not serve other ideals. By the way, I don’t like the word art because I can’t define it. But certain works transcend political or social messages and refer to higher, more universal moral values. Nor do I pretend to deliver an active message. What I am trying to do is to think about the human condition without criticizing or praising it and transferring the (temporary) result of this reflection into sculptures.

Rodin once said that the social value of an artist that should not be underestimated is the fact that he has a great love for his profession and should therefore serve as an example. If everyone chooses the trade they love, we would probably live in a better world.

HVC: Which Belgian sculptors do you think are strong?

AJ: Next week there will be the opening in Mechelen of an exhibition for the Ernest Albert Prize, for which I have been nominated, together with 14 other sculptors. I am really looking forward to exhibiting with people whom I have respected for years. Between all those names there is an Italian, a Japanese and an Arabic name. Does that mean they are also Belgian? It is of course the case that every country has certain social characteristics that shape the person and, in that sense,, we can speak of a national identity. However, we live in a time of globalization, where all borders are opened up as well as where awareness of other social truths from distant or neighboring countries reach us just as quickly. It seems strange to me to still speak of nationalities. Maybe because I no longer really feel connected to a country: I have Iraqi parents but have never been to the country. I was born in Italy and grew up there until I was sixteen, with short trips to Yemen and Moscow. After that I lived in the Netherlands for six years and now, I’ve been in Belgium for ten years. Am I Iraqi, Italian, Dutch or Belgian? I don’t know and probably never will. Sometimes I long to belong to a country. It makes everything simpler. But on the other hand, I now experience myself that it is not important which passport someone has. As humans, we all share the same condition.

Share article