Stone Talk

by Athar Jaber | 6 April 2025

On 15 March 2025, I had a public conversation with Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi at Ayyam Gallery in Dubai, on the occasion of my solo exhibition Vestiges. You can watch a recording of the talk here.

But spoken conversations, especially public ones, can often feel rushed or fragmented, and it’s easy to walk away unsure of what actually came across. I’m not quick on my feet, and I often feel I don’t perform particularly well in front of an audience. I leave these moments doubting whether I’ve managed to communicate my ideas clearly at all. Which made me wonder whether I even have a clear understanding of my own ideas in the first place.

So, I’ve decided to revisit some of the core concepts I touched upon during that talk and take the time to explore them more fully in writing. It’s a slower way of thinking, one that helps me clarify things first and foremost for myself, and hopefully for others as well.

Over the next few issues of Stone Talk, I’ll be publishing short reflections on specific sculpture-related themes that occupy my mind. Please don’t read them as definitive truths, but rather as attempts at articulating my own evolving views. And as such, they might be subject to change over time.

It is my hope they might also open up a broader conversation about sculpture, the act of making, and the ways we shape and are shaped by the world through material and form.

Perhaps this marks a new direction for the newsletter, though I imagine I’ll still alternate these longer pieces with the usual format of five short bullet points highlighting sculpture-related articles, books, podcasts, and other materials worth sharing.

And now, without further ado, what follows is the first essay in this new series.

Thank you for reading.

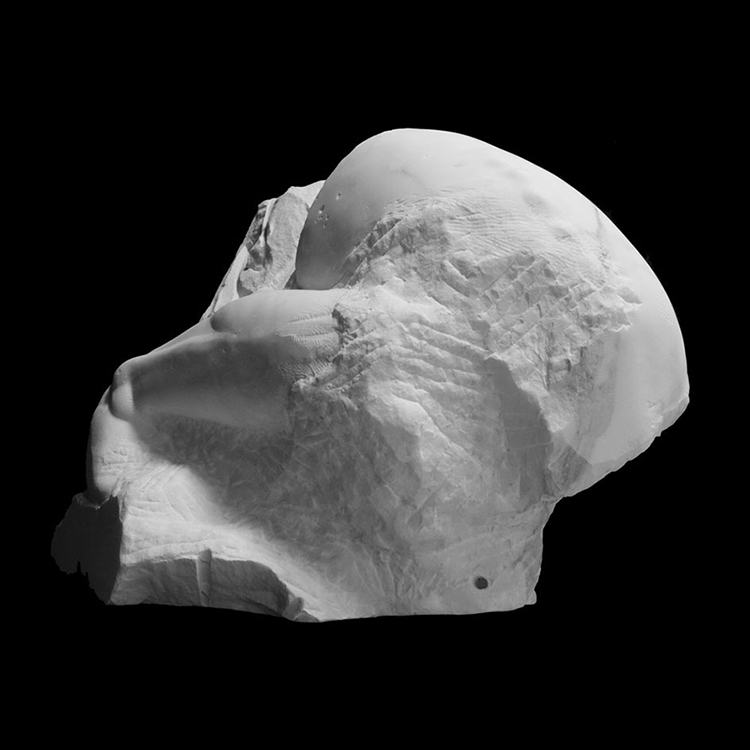

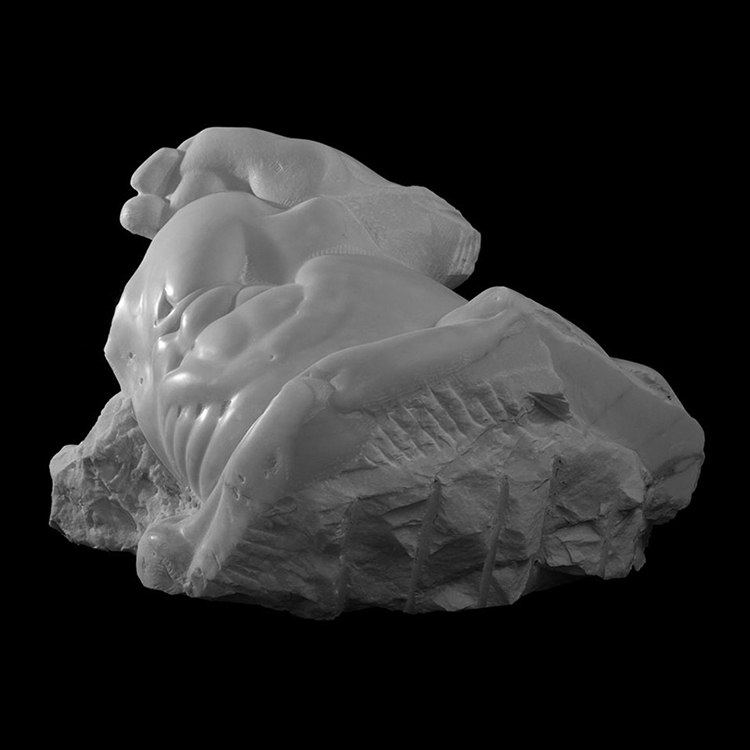

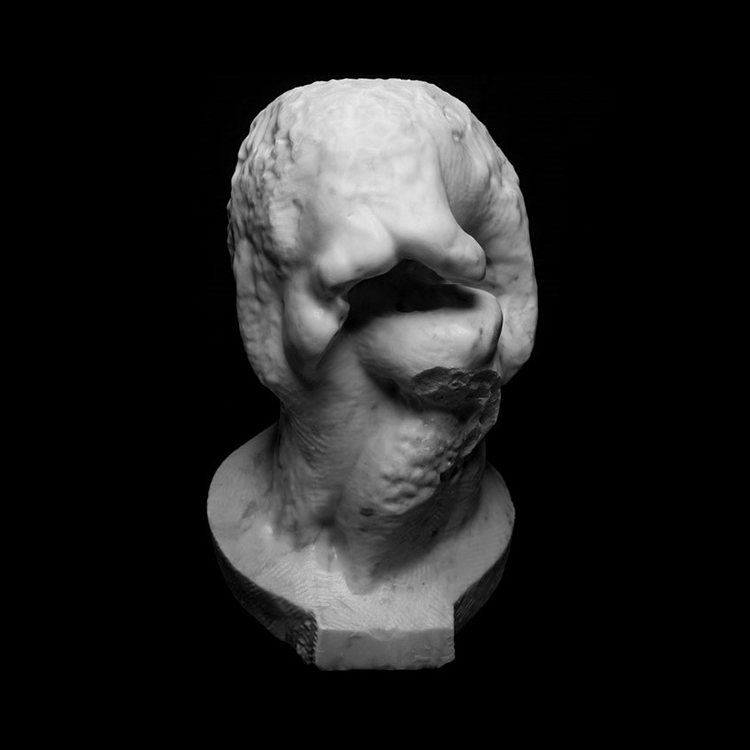

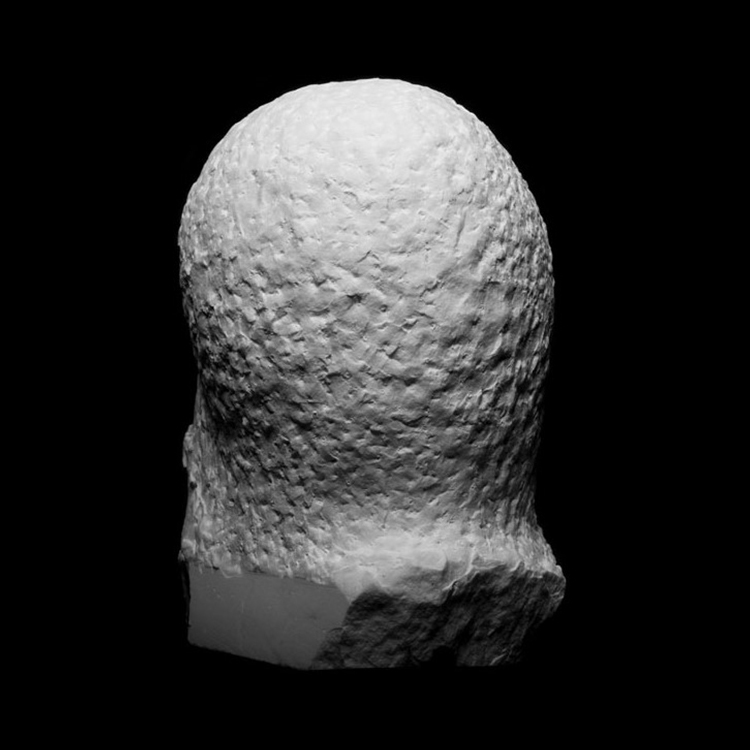

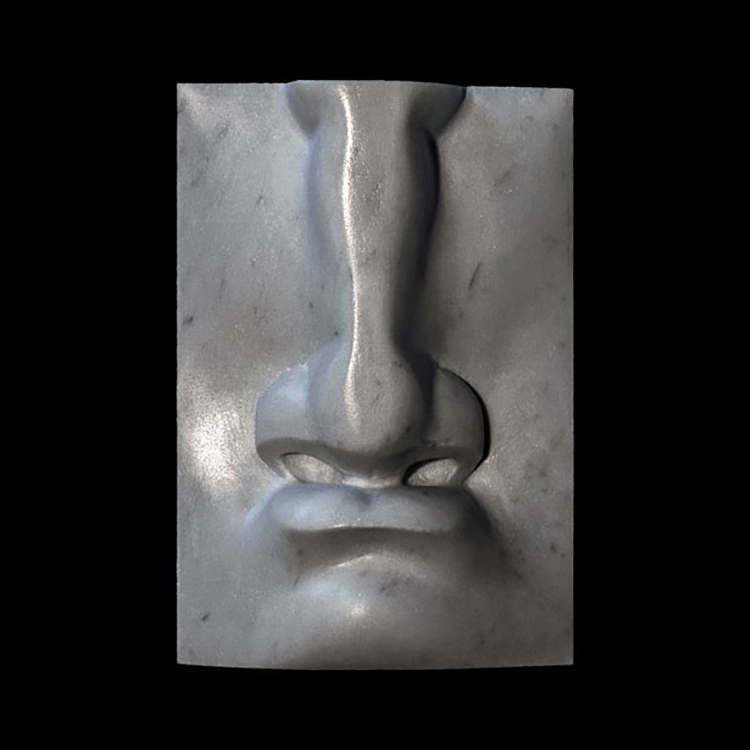

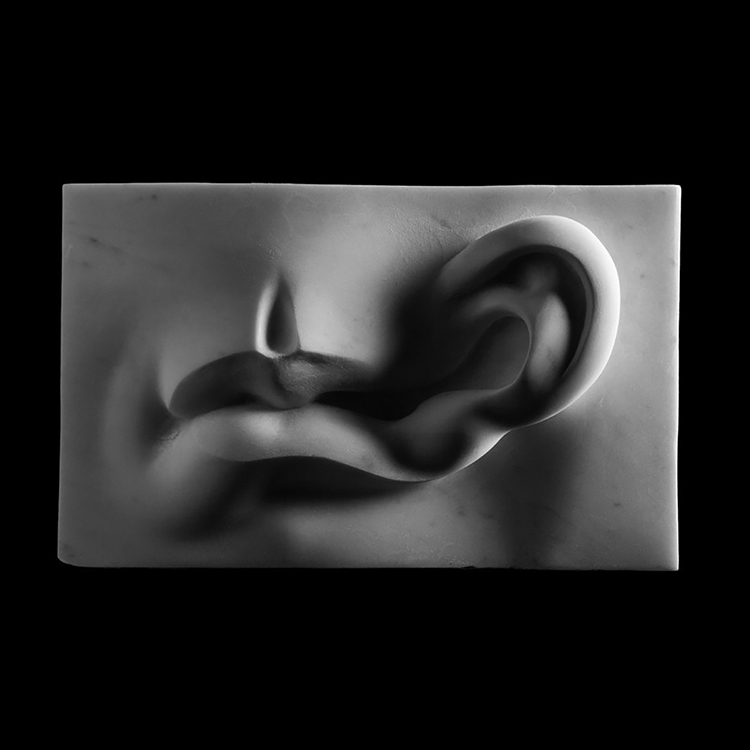

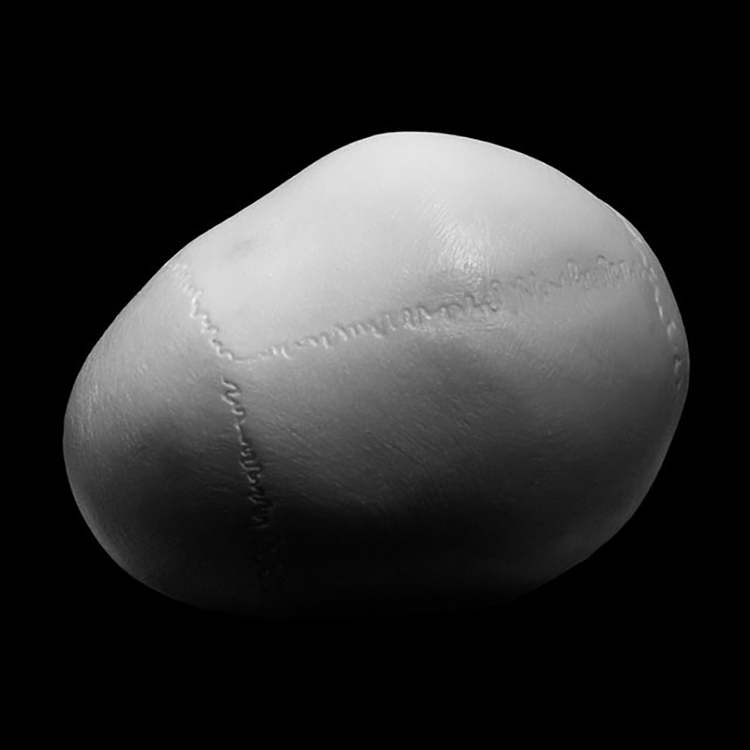

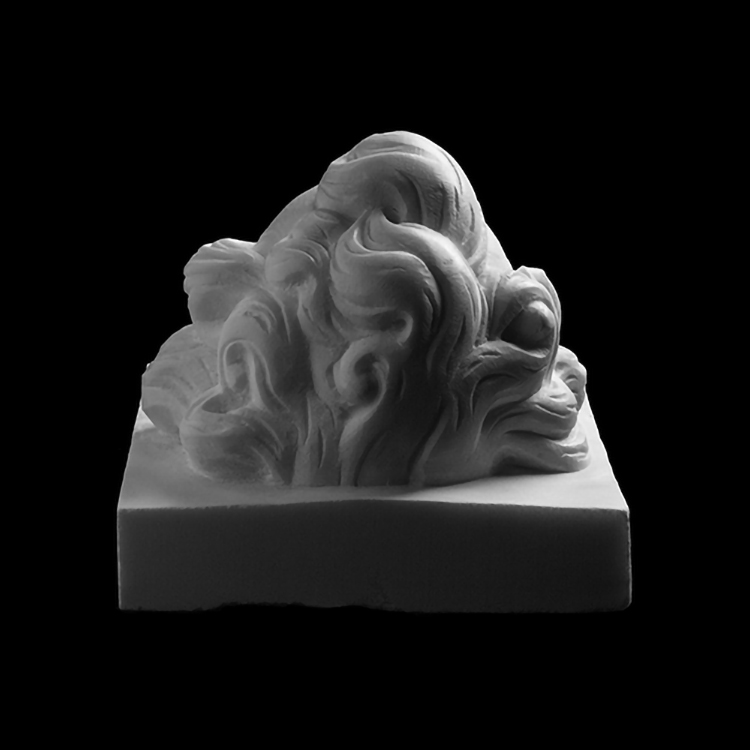

Why I Carve What I Carve: Entropy and the Human Figure in Sculpture

Why I Carve What I Carve: Entropy and the Human Figure in Sculpture

Entropy, in its simplest scientific form, is the natural tendency of systems to move from order to disorder. It is the principle by which all things break down: stars collapse, buildings decay, organisms age. But this movement is not limited to molecules or galaxies. In human culture, too, entropy manifests. Not only as physical decay, but as the unraveling of established forms, systems, and certainties.

Even the arts are subject to this pattern, and they have mirrored this collapse with curious precision. The development of western music, for instance, follows a trajectory that resembles the life cycle of a star. Like vast clouds of gas and dust scattered in space that slowly cluster together to form a star, early musical forms gradually condensed and converged over centuries, culminating in the perfect system Bach gave form to. And like a star that eventually burns through its fuel to either explode or implode, this structure, having reached its peak, began to dissolve: Mozart began to playfully flirt with dissonance, Beethoven dramatically broke with canonical forms, Wagner introduced chromatic instability, and Schoenberg ultimately and definitively dismantled tonal harmony altogether. And then, beyond disruption, came Free Jazz , where rhythms are shattered, harmonies obliterated, and form torn apart. The entropy is both harmonic and formal. It is not simply music anymore; it’s a pure embrace of chaos.

This isn’t unique to music. Literature followed a similar course: from structured epics to modernist fragmentation and postmodern dissolution. In cinema, the classical three-act narrative gave way to jump cuts, nonlinear structures, and surrealist dream-logic. I’m convinced that any expert in any field of art could trace the same trajectory: a shift from coherence to complexity, from harmony to fracture.

***

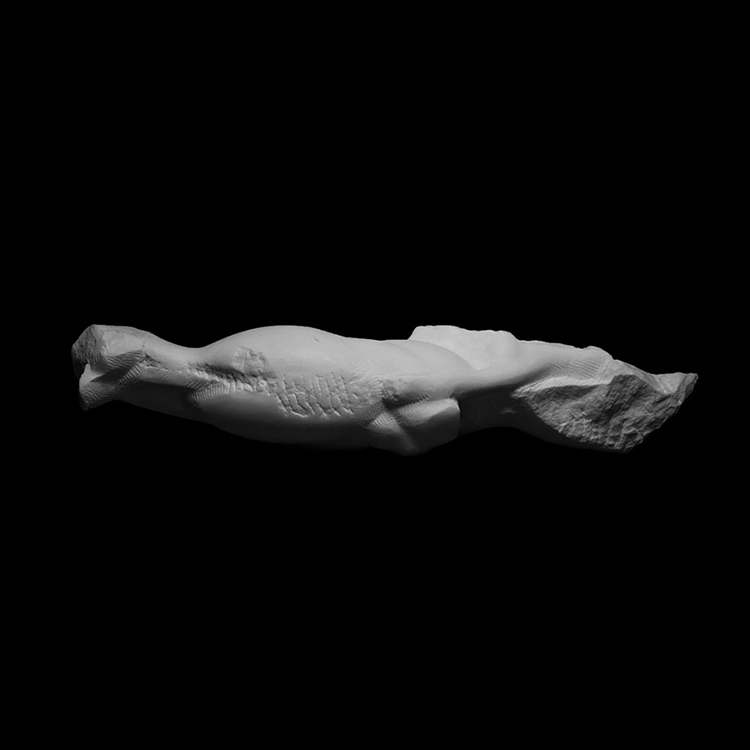

As far as it concerns me, this trajectory is nowhere more evident than in the representation of the human figure in the visual arts—I will try to limit myself to sculpture given my field of work—where it has moved from a compact and rigid depiction to an increasingly dynamic, twisted, unbalanced—and eventually deformed and broken—one. In ancient civilizations such as the Mesopotamian and Egyptian, figures stood or sat stiff and symmetrical. Archaic Greek statues retained this formality, though with a softening of edges. Then, in the Classical period, figures began to subtly redistribute their weight, shifting the body into contrapposto, a now canonical pose in which the body subtly curves into an ‘S’-like shape. By the Hellenistic period, this modest suggestion of movement flowed into twisting torsos, anguished faces, and limbs straining against gravity.

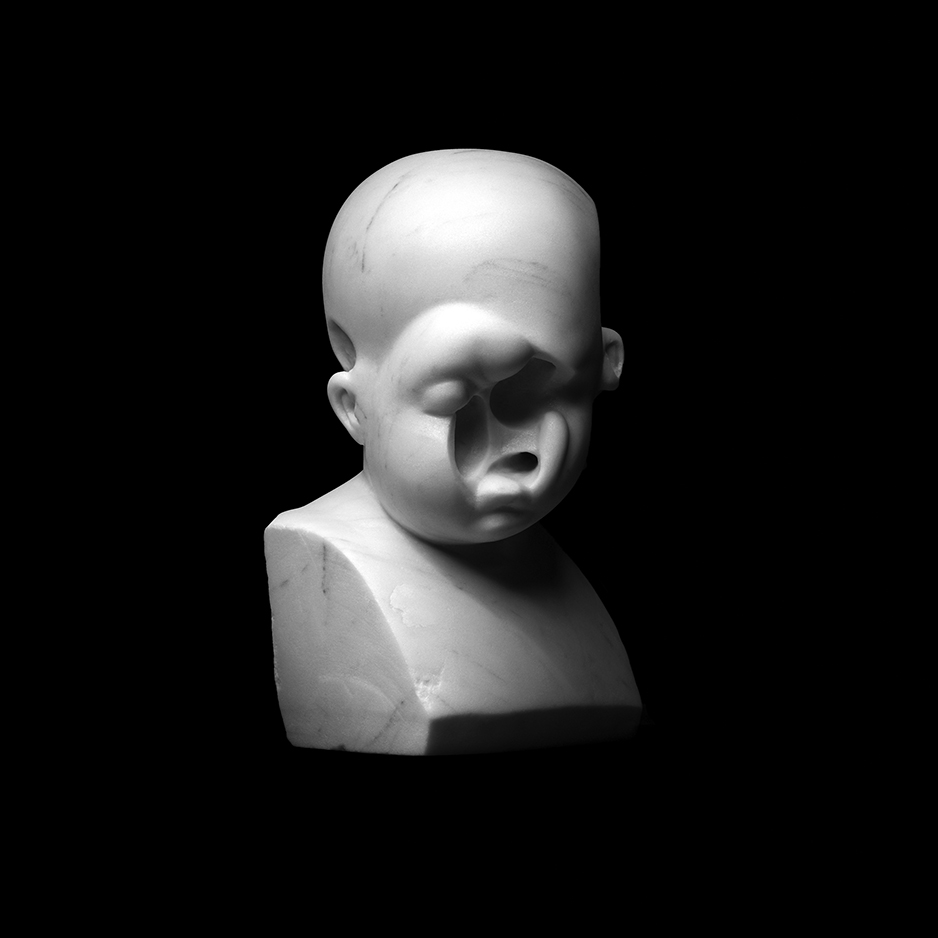

Pathos—Greek for suffering—found its form in sculpture, and the sculpted body was elected to express inner conflict.

Delegating the task of carrying all the world’s suffering to a single body, Medieval Christian society returned to a representation of the human figure characterized by rigidity, as if seeking comfort in the solemn order of earlier civilizations. But the Renaissance revived the classical era’s pursuit of (gentle) movement and anatomical accuracy, culminating in Michelangelo’s David—a figure so perfect, that it has come to symbolize the summit of the Western sculptural tradition. But as with a star that, having reached peak luminosity, begins to burn through its fuel, like Bach’s resolution of centuries of musical searching into a complete system, after which the structure began to dissolve—beyond this point, the only natural consequence was decay (not to be intended as a pejorative).

Mannerism, Baroque, and Rococo began twisting the figure as much as anatomically possible, while artists like Goya deliberately introduced the first true ruptures, registering horror and disillusionment.

Simultaneous counter-movements emerged, testifying to our societal impulse to counter disorder, resist fragmentation, preserve the status quo, and reassert control. In 1755, the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann wrote that “the one way for us to become great, perhaps inimitable, is by imitating the ancients.” And Neoclassicism did just that, it depicted the figure in the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” of the Greeks. Composed, poised, and in its full, perfect glory. Yet this restoration of classical balance was short-lived as the aesthetic of collapse gained momentum in increasingly larger waves. Neoclassicism was a mere pause, a brief correctional movement to hold entropy at bay before a new wave of destruction broke it apart once more.

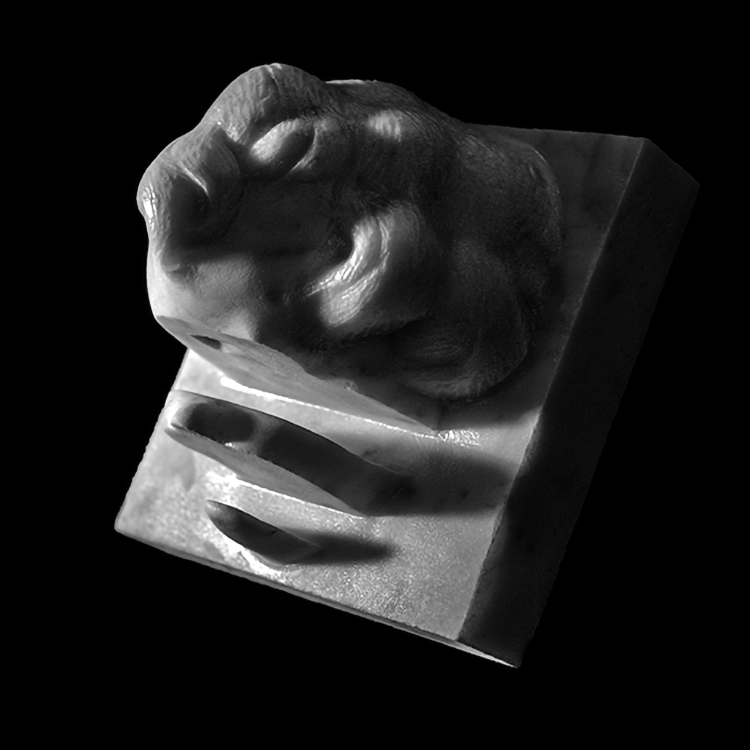

The appearance of Auguste Rodin marks the beginning of modernity: the figure’s proportions are unbalanced, its limbs distorted, broken, fragmented. Giacometti presents a figure that stands—both literally and figuratively—as a projection of existential perception. The advent of Cubism, its embrace of non-Western aesthetics, and the haunting imagery of global wars—now carried through increasingly pervasive news channels—all contributed to the further disruption of the human form. Picasso further inspired the total annihilation of bodily integrity—by now an abject thing—as portrayed by Francis Bacon, whose infamous silent scream is desperately wailed through the saxophones of John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders in their gut-wrenching Olatunji Concert, recorded shortly before Coltrane’s death. Artists push further, not for effect, but because the previous expression no longer sufficed.

In keeping with the ancients’ aim to use the human body as a vessel for expressing the soul, these exaggerated deformations reflect a more encompassing perception of a universal human condition.

Just as molecules lose their cohesion under entropy, the ancient, rigid, severe, and awe-inspiring body becomes a shattered, wretched, miserable, and desecrated figure. And alongside the collapsing figure, perhaps our very concept of humanity itself begins to fall apart. In a post-human era, as our identity as human beings enters a new crisis, what does it even mean to be whole?

***

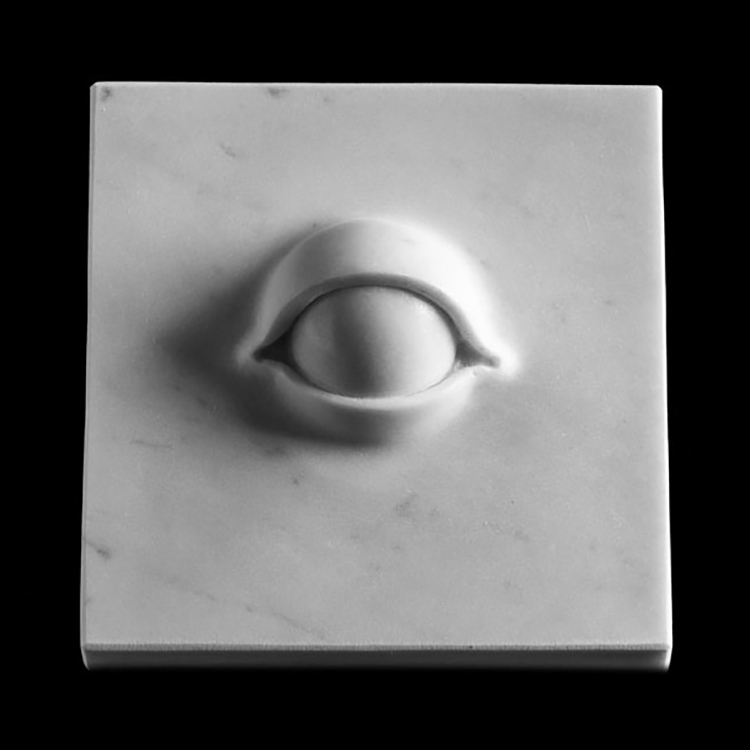

These distortions are not arbitrary, nor are they driven by a fascination with the aesthetics of (literary or cinematic) horror, as is often assumed. Rather, they are reflections that respond to both internal and external states: the movement of the soul, and the sickness of the world.

Pain, crisis, and trauma have always existed. And in sculpture, the human body has long served as a vessel for expressing them. One could argue that all art, across all media, ultimately returns to the same set of human emotions—pain, love, struggle, joy, wonder, displacement… The list is vast, but nonetheless finite; it is this recurrence that defines our humanity. What changes over time is not what we feel, but how we express it. And this expression is always shaped by the historical moment and its contemporary aesthetic vocabulary.

What has changed most radically in our time is not the presence of suffering, but our awareness of its pervasiveness. Media, once localized and delayed, now functions as a global nervous system. We wake daily to images of destruction—war, famine, oppression, collapse—looping endlessly across our screens. What was once perceived as an exceptional, isolated crisis is now understood as continuous and ubiquitous, without resolution in sight.

In this permanent state of crisis, we are no longer dealing with singular traumas, but with the normalization of horror. And in such a world, to portray the body in its integrity feels detached from reality.

If the human figure has always served as a mirror of collective consciousness—of how we see ourselves—then in this era of fragmentation, moral collapse, and societal disorientation, the body, too, must reflect that rupture. It must be fractured, twisted, scarred. It must carry the marks of its time.

But over time, even those marks begin to fade—not from the body itself, but from our perception of it. As images of suffering become constant, we stop seeing them for what they are. We grow numb.

This desensitization may help explain the progression toward an increasingly violent and radical aesthetic. Because what once scandalized eventually becomes aestheticized.

Consider the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. The music was so jarring that it provoked a riot. Today, it’s performed in concert halls around the world to polite applause. Similarly, the rawness of Bacon’s work has been absorbed into the canon—his trauma commodified; his screaming figures auctioned for millions.

This is not necessarily a betrayal—it’s simply how culture works. But it means that artists must keep moving. As aesthetic boundaries become normalized, they must be breached again. If an image once deemed unbearable by audiences no longer stirs us, then we must find a new visual language. A more radical deformation, not to provoke, not to shock, but to stay truthful. To reach the nerve endings that have gone numb.

***

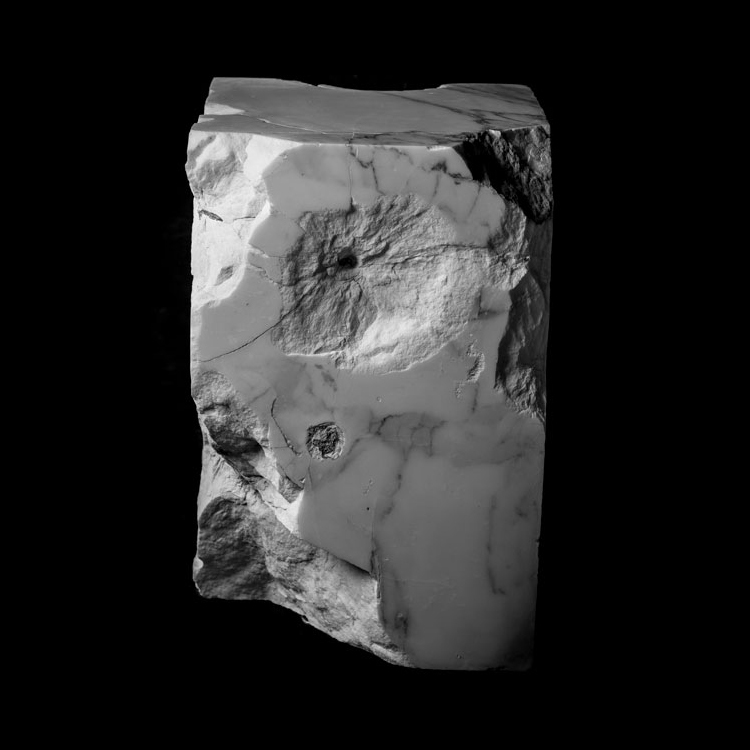

I’m often asked why I fill marble with anxiety, rupture, and pain—why I distort what could be ideal, why I don’t carve beautiful things. I understand the impulse behind the questions. Beauty comforts. It offers relief, even escape. And I would love to carve the human figure in its full dignity and glory, as the ancients once did. I admire those works deeply—their harmony, their serenity, their timeless poise.

But my choice not to pursue that ideal isn’t born from rejection or disdain—it comes from an ethical alignment with the present. To carve such beauty today, without acknowledging the world we live in, would feel like evasion. It would be a dissonance not of form, but of truth. The body I carve must belong to this time, not another.

Furthermore, in a world saturated with suffering, to carve beauty for beauty’s sake would mean producing decorative objects to soothe those privileged enough to ignore the world’s wounds; to distract those that prefer to forget, to cancel out the horrific images of distant suffering by surrounding themselves with beautiful objects of denial. It would mean entertaining the very classes often responsible for that violence, whether directly or indirectly. It becomes aesthetic anesthesia—a way of numbing, not awakening. And that, to me, feels complicit. As Publilius Syrus wrote: “He who helps the guilty shares the crime.”

I don’t have the power to end injustice. I’m not a politician—a title that has, in any case, been hollowed out by corruption and self-interest—nor am I an activist in the traditional sense. But I can carve. And in carving, I can denounce. As Noam Chomsky once argued in “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” the role of those with a voice is not to serve power, but to expose its abuses. I take that responsibility seriously—in my own way, through sculpture.

There’s a moment in the play One Night in Miami by Kemp Powers, where Malcolm X critiques Sam Cooke for performing songs that entertain the very people oppressing him, while praising Bob Dylan, who uses his music as a weapon of truth-telling. Sam eventually goes on to do the same. Admittedly, they both used a beautiful, accessible aesthetic to do it, and I admire that. Just as I admire artists who manage to balance aesthetic beauty with urgent content. Like my dear friend Jago: his sculpture Figlio Velato confronts death, innocence, and injustice with haunting beauty. That’s a rare gift. I don’t seem to be capable of—or perhaps not interested in—that kind of balance. Each artist has their own voice. Perhaps mine is more like the less accessible Free Jazz: raw, unfiltered, dissonant.

***

Entropy is not a tragic fate, it’s a condition of reality. It is what we live within. And in art, it offers not only a metaphor, but a method. A way of understanding the breakdown of systems, bodies, meanings. A way of carving meaning from fracture.

I do not break the body to desecrate it, but to tell the reality I see. To reflect the disintegration that surrounds us. And perhaps, in confronting the brokenness, we find not only clarity—but a strange, unexpected form of beauty. A beauty not of surfaces, but of honesty. To carve the voids, the absences, the ruptures—not as nihilism, but as testimony.

This is not an aesthetic of despair. It is, first, an aesthetic of confrontation with reality; second, of denunciation; and ultimately, of acceptance—a reckoning with the human condition, which has always been marked by its own historical violence. This does not mean surrender. Even if I believe that such brutality is embedded in our nature, we must nonetheless engage in a utopian effort to resist it.

Ultimately, to acknowledge and accept entropy and its inevitable trajectory toward dismemberment, of ourselves and of our structures, our cultures, our histories—is to face the fate that awaits us, while still striving to make the most of our time on this wounded planet we continue to violate.

6 April 2025, Abu Dhabi

Note: This is a live essay. Meaning that I will keep working at it and edit it through time as my ideas develop or I find better ways to express my thoughts in writing. The date of the last edit will be mentioned at the bottom.

The Enduring Power of Interactive Sculpture

The term ‘interactive sculpture’ is usually associated with contemporary artworks that react to the presence of the viewer, usually through technology or participatory elements. These works often rely on sensory triggers like sound, light, or movement, captivating audiences through their dynamics and novelty. However, as technology evolves, these sculptures risk becoming outdated, and their initial allure fading into obsolescence.

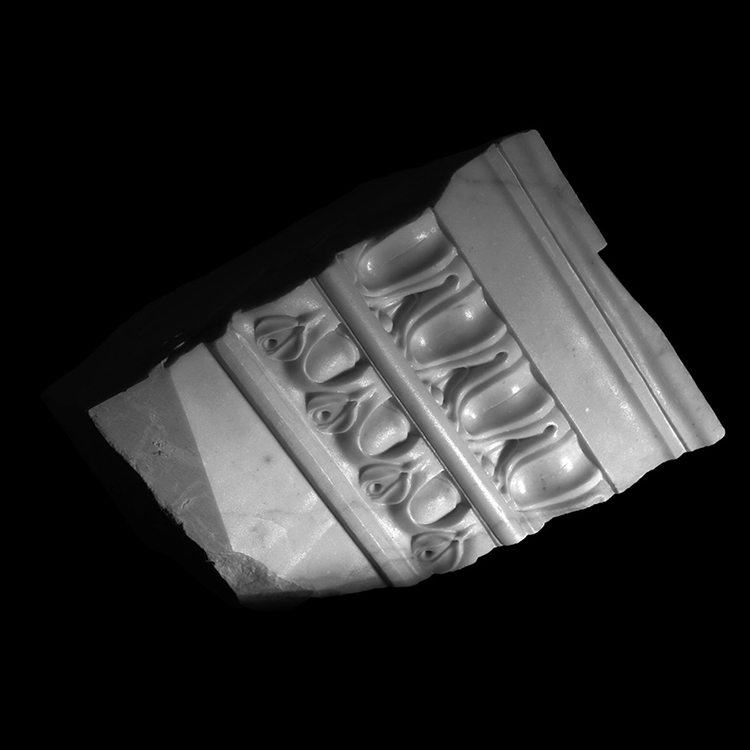

In contrast, stone sculpture represents an enduring form of interactivity that is subtler yet profoundly impactful. While stone does not offer the immediate dynamism of its high-tech counterparts, it invites a deeper kind of engagement—one that unfolds emotionally and intellectually, often inspiring a spiritual connection. The timeless quality of stone demands a slower, more reflective interaction, encouraging viewers to contemplate the weight of history and the permanence of the material.

The Historical Roots of Interactive Sculpture

Sculpture has always been interactive, even if it was not explicitly referred to as such. Throughout history, sculptures have played a central role in human society, serving as visual representations of powers—natural, spiritual, or political—that were believed to govern the world. In fact, the term ‘monument’ stems from the Latin monere, meaning ‘to admonish,’ underscoring the role of these structures in reminding communities of the higher powers they revered.

In their role as visual representations of these authorities, sculptures became recipients of active engagement from communities. They were worshipped and cared for; offerings such as gifts, food, or oils were regularly presented to them. This interaction was rooted in the belief that these acts could invoke divine favor, bringing healing, good harvests, or protection. Far from ephemeral entertainment, the interaction between sculpture and society was deeply consequential, reinforcing the relationship between humans and the forces they revered.

Until relatively recently, sculptures were primarily intended to be engaged frontally. They were often placed against walls or in niches, creating a visual hierarchy that encouraged viewers to connect with them as if they were royalty—respectfully, reverently, and from a distance. This static relationship between the viewer and the sculpture persisted for centuries.

The Late Renaissance introduced a pivotal shift in how sculptures were designed and experienced. Pioneer sculptors developed a compositional technique known as figura serpentinata, in which the multiple figures within a sculptural composition would each face different directions. These dynamic arrangements prompted viewers to walk around the sculpture, experiencing it from various angles. Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine (1582) is a striking example of this technique. This monumental marble sculpture features a spiraling composition of three interlocking figures, compelling the viewer to move around it to grasp their dramatic interplay. Often placed in the center of palace courtyards, such works invited motion, transforming the act of viewing into a participatory experience. For the first time, the viewer’s movement became an integral part of the sculpture’s meaning, adding a novel dynamic aspect to the interaction.

This dynamic, circular movement of interaction is not confined to art alone. In Mecca, pilgrims engage in a circular wandering around the Kaaba. This spiraling circumambulation culminates at the Black Stone embedded in one of the Kaaba’s corners, where pilgrims touch, kiss, and bless the sacred stone in acts of profound devotion. Here, the physical act of movement is inseparable from the emotional and spiritual transformation it inspires—a perfect illustration of how something can “move” us both physically and spiritually.

Other sacred stones across the world offer similar examples of interactive engagement for various faiths. The Stone of Anointing in Jerusalem invites worshippers to kneel, pray, kiss it, rub oils onto it, or press garments against it in acts of reverence. At the Wailing Wall, also in Jerusalem, individuals place their heads against the stone to pray or leave written prayers in its crevices, embedding personal hopes and connections into the material itself.

In other religions, stones become the recipient of offerings such as milk, blood, oils, flowers, and edibles during rituals, symbolizing a profound connection between the material and the divine. These examples highlight how sacred stones transcend their physicality to become vessels for collective faith and spiritual interaction.

These examples demonstrate that sculptures and other stone artifacts’ purpose has rarely been limited to passive viewing. Interactivity has always been an intrinsic aspect of sculpture. Whether experienced through physical movement or spiritual engagement, sculptures have consistently invited interaction, reminding us that their power lies not only in their materiality but in the connections they inspire.

Community Engagement Through Sculpture

As shown above, interactive sculptures have the ability to transform public spaces into shared spaces where communities come together. Whether playful, poetic, or introspective, their true power lies in their capacity to unite people from diverse backgrounds. These works create focal points for gatherings, celebrations, and moments of reflection. By inviting participation and inspiring a sense of belonging, they enrich the shared experiences of those who encounter them, fostering pride and strengthening the bonds that hold communities together.

I experienced this firsthand growing up in Florence, Italy. Though I was not an Italian citizen, I felt deeply connected to the city and its artistic heritage. I vividly remember spending hours under the Loggia dei Lanzi, sketching the sculptures it houses. I would run my fingers along the intricate reliefs on the marble pedestal of Cellini’s Perseus, captivated by its details and craftsmanship. As I traced the stone, I often thought of the countless others who had touched it before me, feeling a connection to past generations that seemed to transcend time.

These monuments and my interactions with them planted the seeds of belonging to a city whose beauty shaped not only my identity but also that of Florence itself. Their stories, carved in stone, have long been intertwined with the city’s narrative, inspiring pride and connection across generations. Remarkably, this legacy stems from commitments made by Florence’s cultural players over 600 years ago—a testament to the enduring impact of public art.

Florence’s artistic heritage demonstrates that investing in meaningful and accessible public art enriches communities not only in the present but for generations to come. These works transform cities into living histories, fostering connections that make citizens active participants in their cultural narrative. This legacy reminds us that today’s cultural leaders have the opportunity to create similar enduring contributions by championing thoughtful public monuments that reflect and strengthen the identity of their communities.

Conclusion

The enduring legacies of public monuments show us that the power of sculpture lies not only in its ability to adorn spaces but also in its capacity to engage, connect, and transform. Interactivity—whether through physical movement, emotional resonance, or cultural meaning—is what breathes life into these works, allowing them to remain relevant and impactful across generations.

Interactive sculptures are far more than objects defined by superficial movement or sensory triggers; While some works may rely on sound, motion, or light to captivate viewers, the true essence of interactivity lies in deeper, more lasting exchanges. These sculptures engage the intellect and emotions, shape cultural identities, and foster collective meaning. Crucially, this interaction is reciprocal: just as sculptures act on their audiences, audiences in turn imbue them with layers of memory and interpretation, ensuring their continued relevance and meaningful endurance in time.

Thank you for your time.

Athar

Join the talk

On Sundays, at irregular intervals, I send out Stone Talk, a newsletter where you’ll find tips and recommendations on things I believe are worth watching, listening, reading, visiting or exploring. All related to (stone) sculpture and stone carving. And sometimes I use the space to put down my thoughts on specific (sculpture related) topics.

The newsletter is also a great way to stay updated with my artistic activities such as exhibitions, new works, limited editions, publications, as well as my educational activities such as courses, workshops, lectures, tutorials and much more.

If you wish to subscribe to Stone Talk, please fill in the form.