Sculpting Identities: Athar Jaber is making sense of violence through art

An interview with Maan Jalal

Khaleeji Times

March 2017

This is your first time exhibiting in Art Dubai. What do you think of the fair?

I really love the fair. I haven’t seen the really big fairs, like Basel and Frieze, but from what I’ve seen, honestly this is one of my favourites. Not only because of the booths but mainly because of the artists talks and the Global Forum. There are some really in-depth theoretical discussions going on.

Why did you choose sculpture as your chosen medium?

I was always attracted to marble. You know my family is a family of painters, mother, father, uncle, they are all painters. So I started drawing and painting when I was a kid. But then since I grew up in Florence, I used to draw the sculptures in the city just to train myself and to have fun. I think the love of sculpture started there. When I decided to study art, I didn’t even have to think about it, I knew I wanted to do sculpture, I didn’t consider painting.

Where do your aesthetic influences come from?

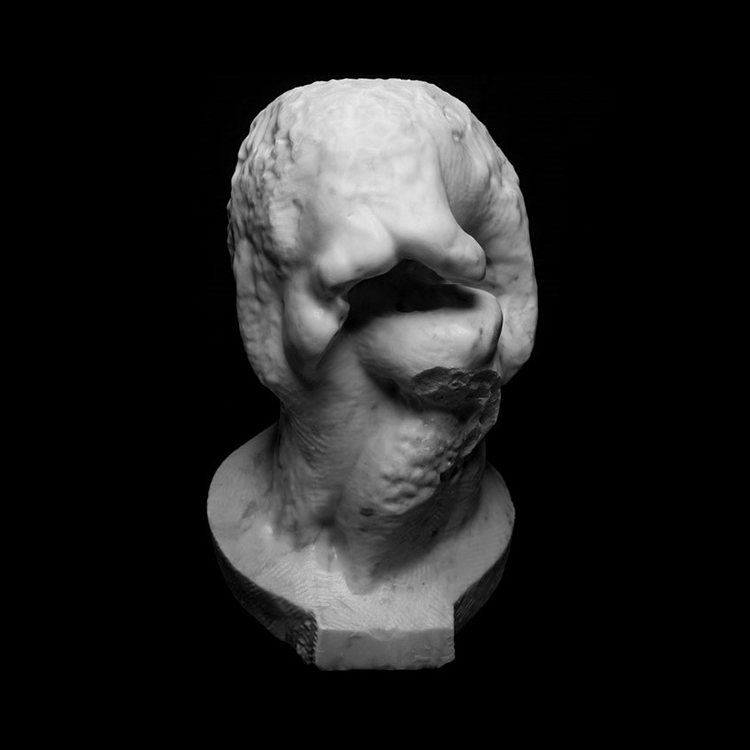

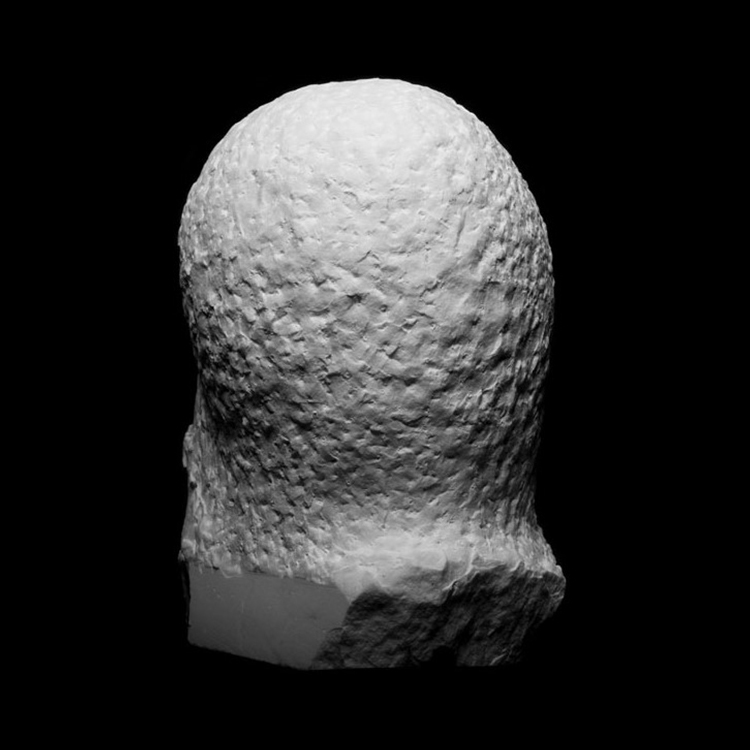

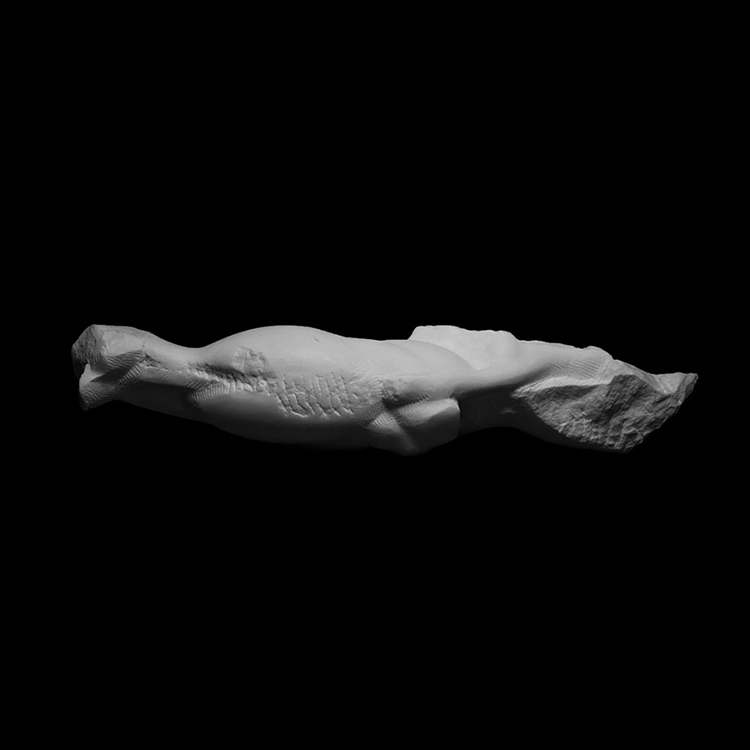

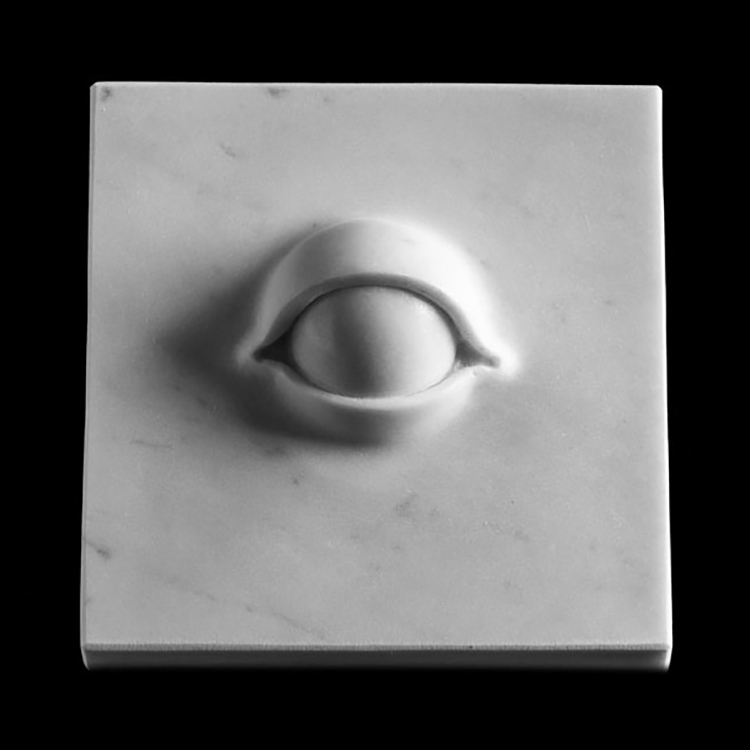

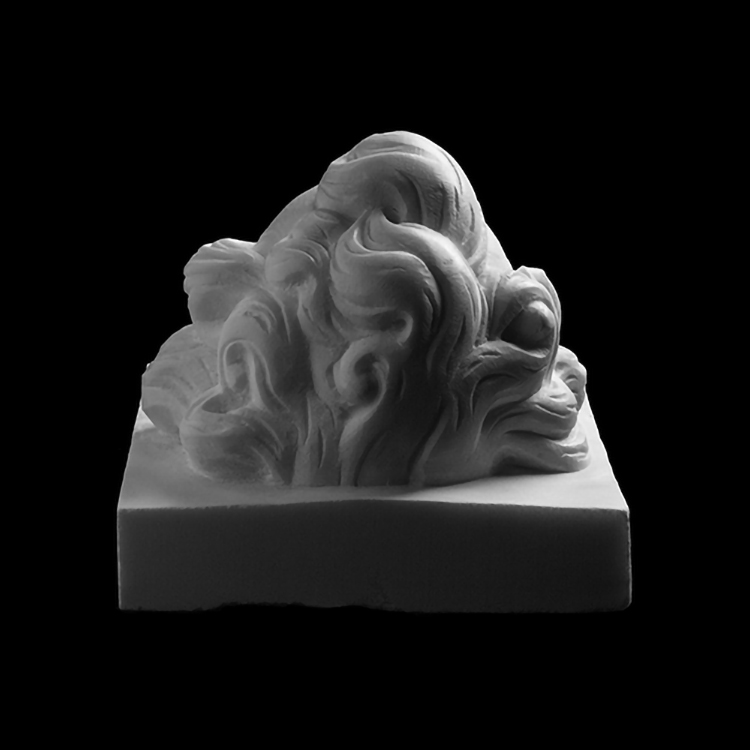

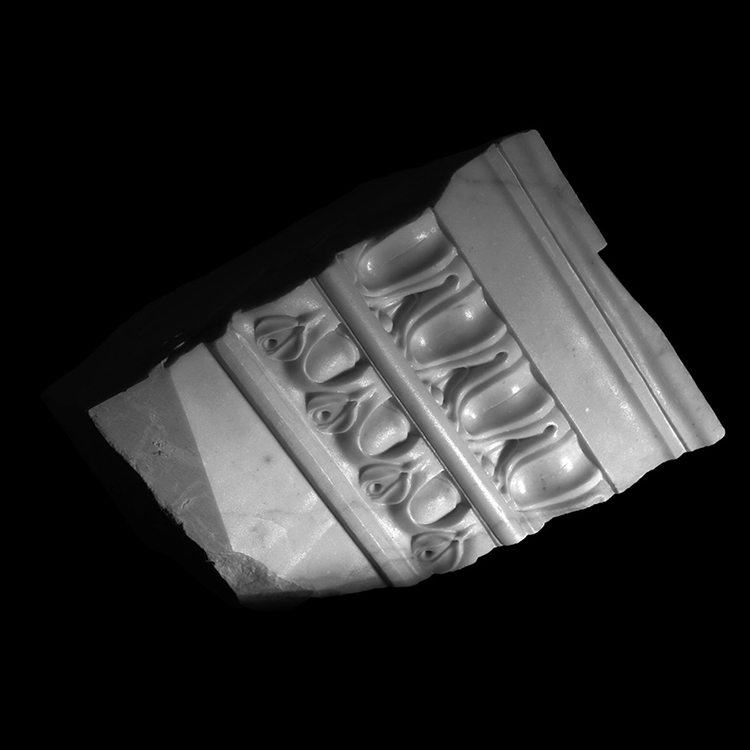

Mainly from Italy. The Renaissance sculptures, which focus on the human anatomy, have been a major influence on me. But again this destructive aspect. it’s more of a theoretical level from what’s happening in Iraq. The situation there is bad. But also the fact that I’m going more towards abstract works as well is a kind of reference to the Islamic tradition of working with abstract art.

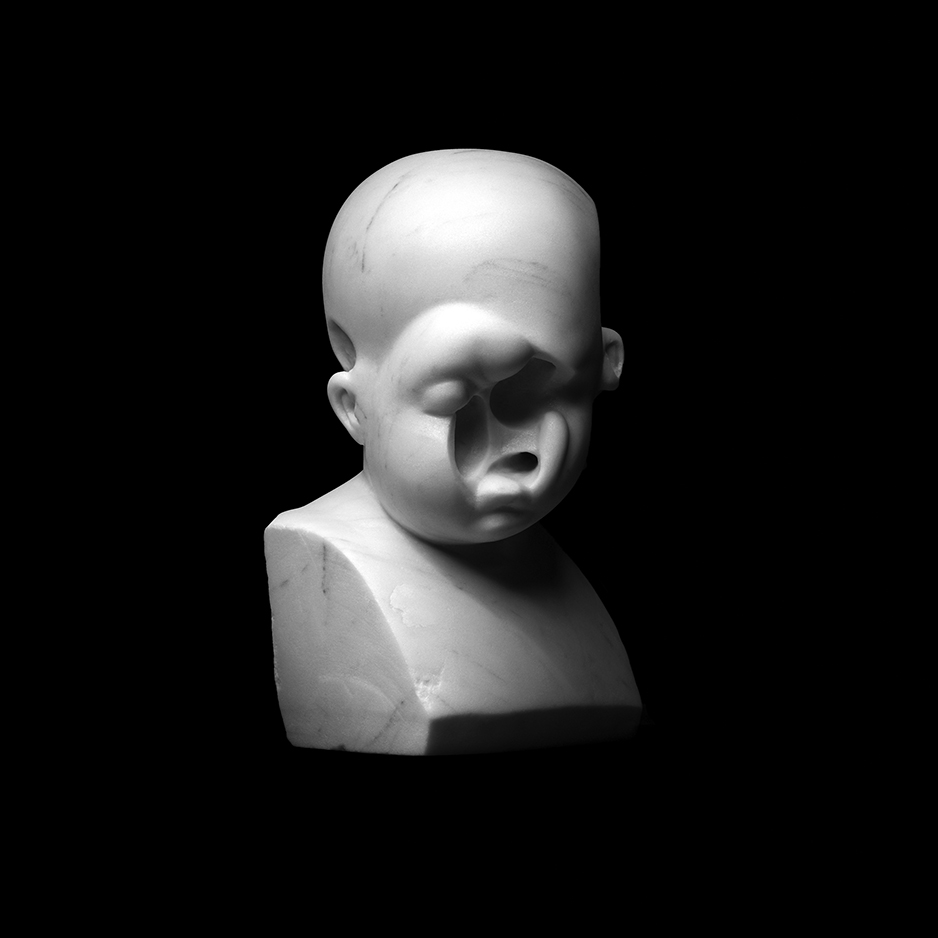

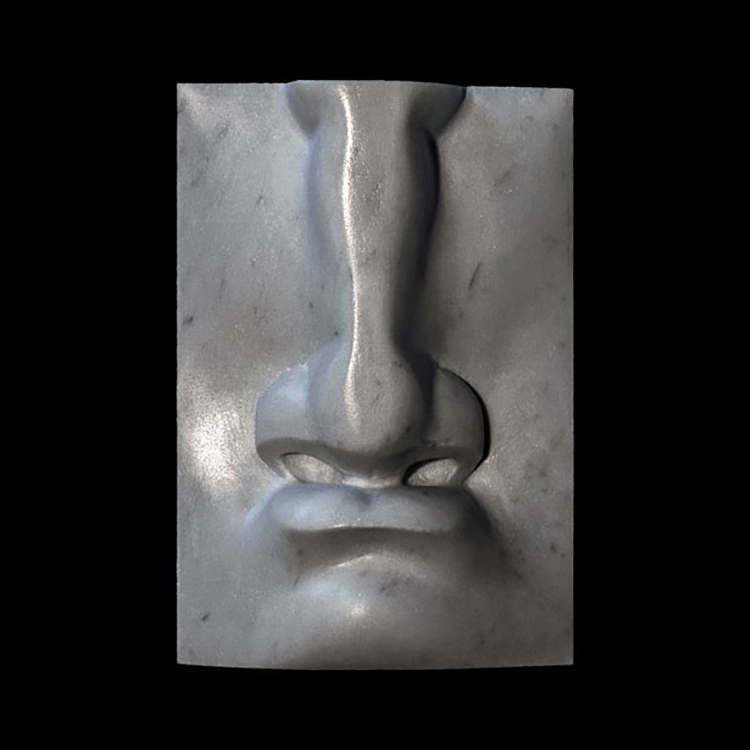

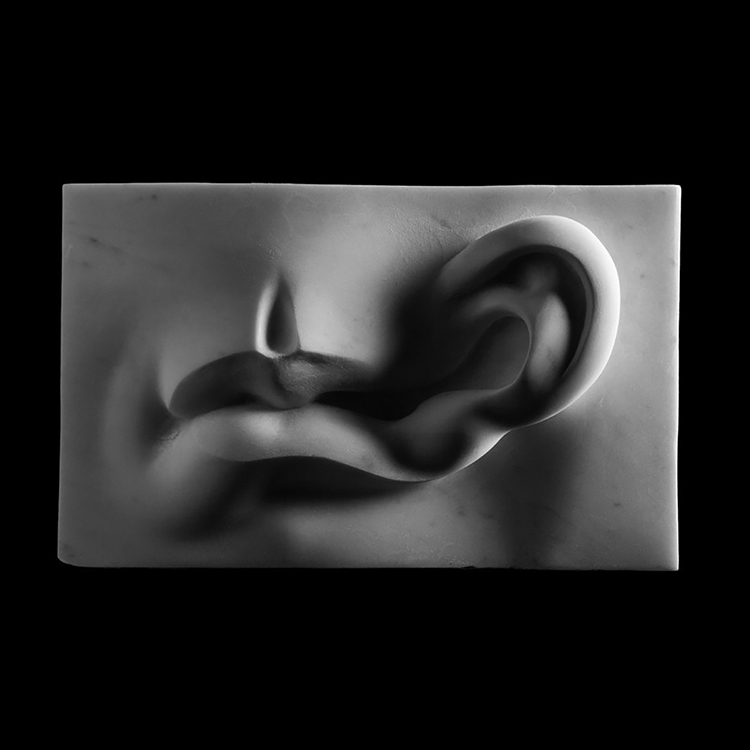

The human anatomy is a big part of your work. Why?

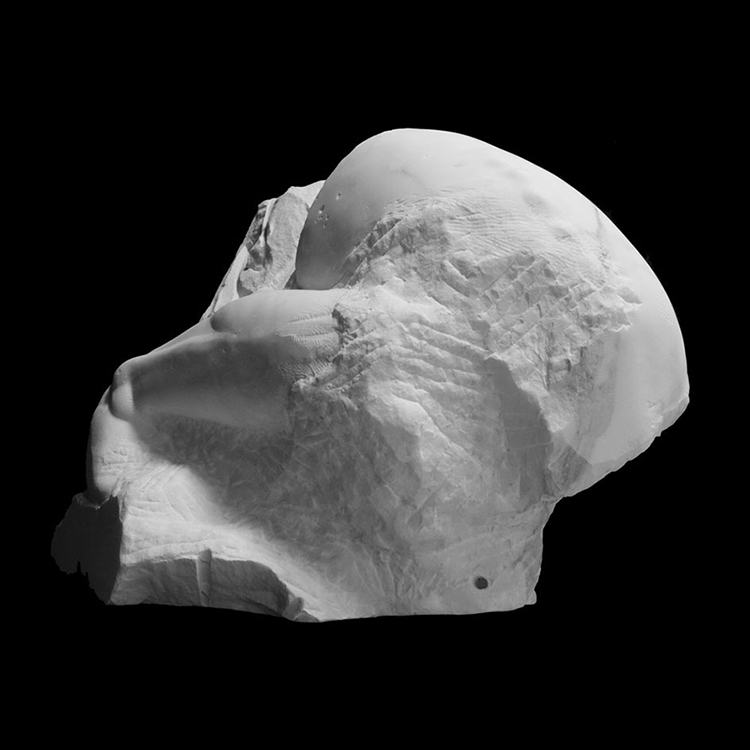

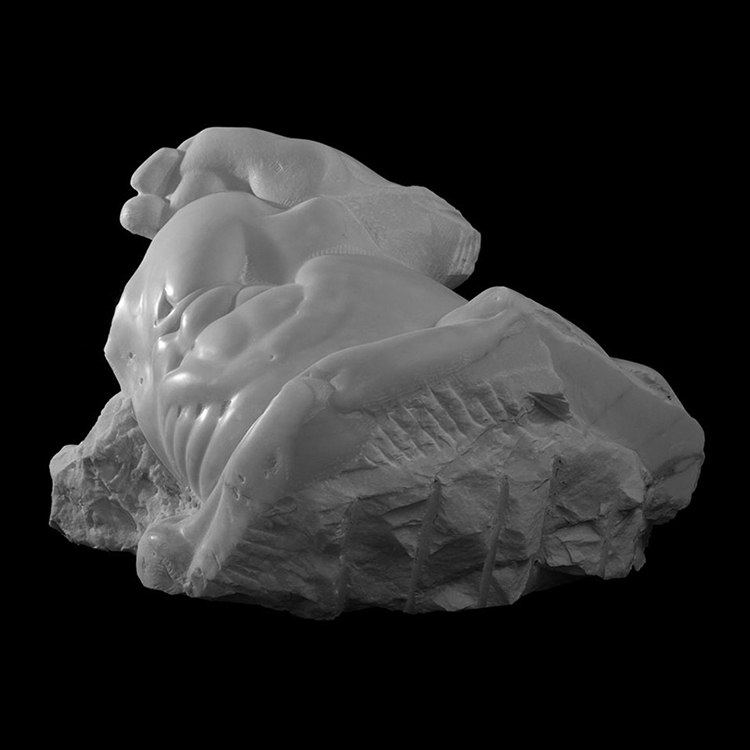

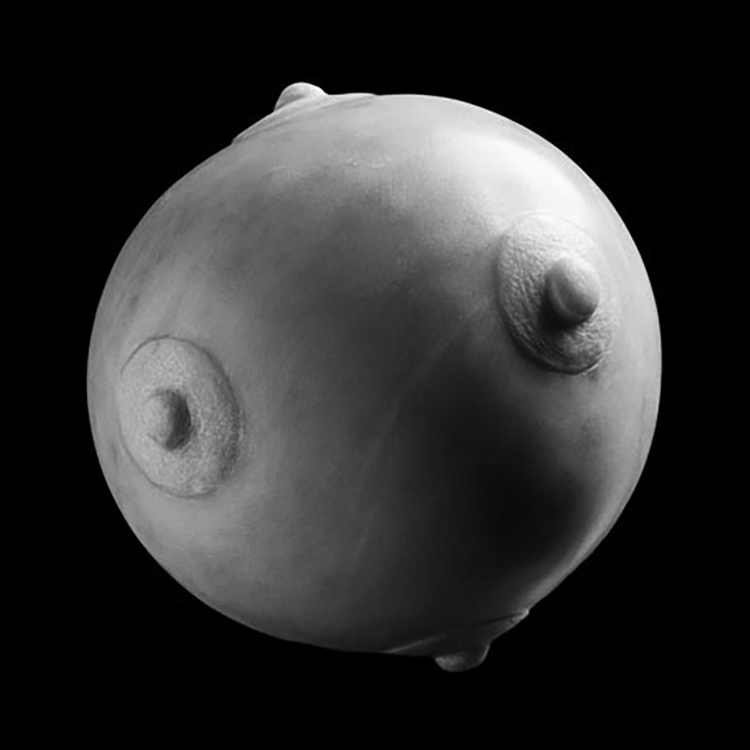

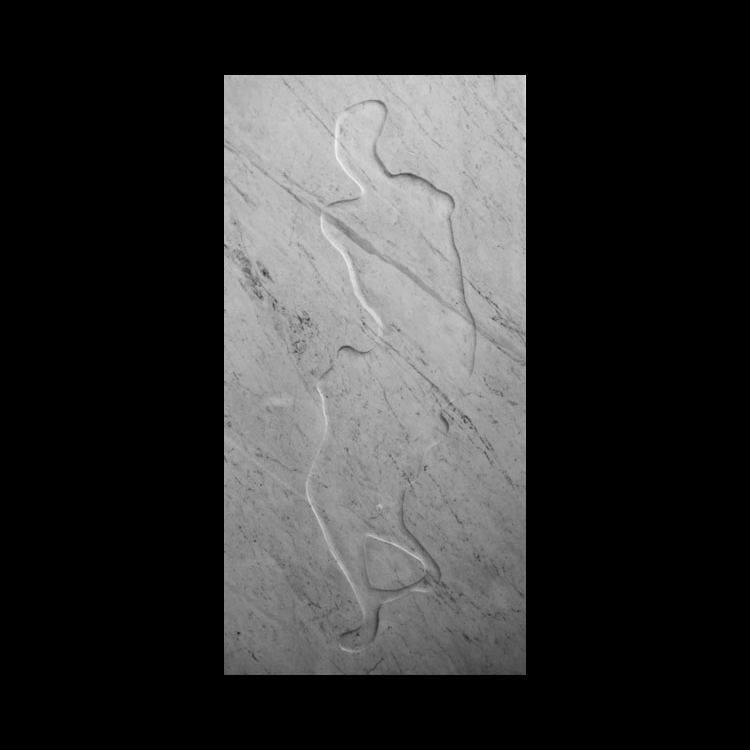

I think because growing up in Florence and having my parents who were more classically inclined in painting and of course, sculptures and the Renaissance, I grew up with that idea of the beauty of the human body and the language of the human body. But I wanted to do something with it. That’s why I want to deform it. I like working on the human body as a classic theme but it doesn’t make sense to just make beautiful things. You need to do something with it, either deform it or destroy it with acid or bullets or whatever.

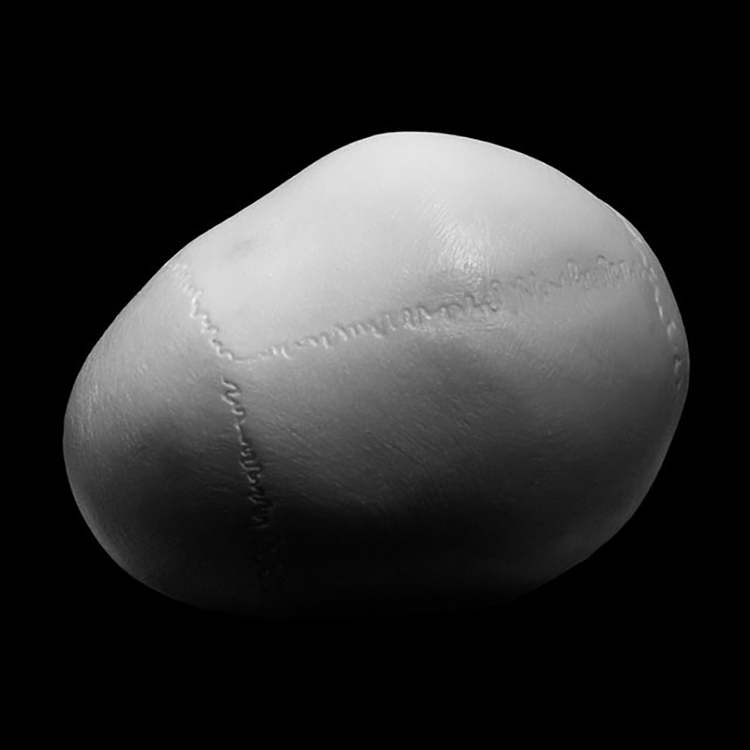

Tell us why you started this method of destroying parts of your pieces.

It’s a fact of nature. Sooner or later everything will be destroyed, no? We are going to die unfortunately and we have to face that fact and not in a negative way, it’s the engine that keeps us going, to create stuff, having the knowledge that all of this will end. Nature will also eventually destroy things with earthquakes and acid rains. I think we as humans are inclined toward violence somehow. Even kids when you see them playing, they make things and break them. At least I’m not destroying other people’s work, I’m doing it with my own work.

Violence and identity are a common theme in your work. Can you explain why?

There is this uneasiness of not knowing where you belong. I just don’t feel at home anywhere and I feel at home everywhere. And I think growing up seeing the images of the war in Iraq as a small kid had an impact. Of course I haven’t lived the war but I’ve seen them through images on TV. As a kid, you already realise there is something horrible happening, parallel to your own life, because I was living in Italy and everything was beautiful, sculpture, art, culture – normal life and parallel to that, you saw the images on TV of Iraq and you knew that your family was there. So there is this parallel between beauty and the whole situation there. I think it’s an attempt to combine those two things, those two realities when they are side to side.

Can you explain your process when creating a work?

I try not to stick too much to my original plan or ideas. The best thing that can happen are mistakes. Because they open up your mind, they face you with new kinds of problems that you may not have had and you develop yourself in searching for a new solution for that problem. It’s like life.

How do you know when a piece is complete?

You know it on an instinct level. It’s done when I have the feeling that there’s nothing I can add to it. My efforts will not include the overall aesthetic or message of the work. But really, it’s on an instinctual level.

Social media is problematic for many artists. How would you describe your relationship with it?

It’s a love and hate relationship. I hate myself every time I post anything, I don’t like to do it actually but I know that the world is on social media, so if you want to communicate what you’re doing, we are a society of imagery, so you need to do it. If you’re ambitious, if you want to be in galleries and fairs and museums and reach collectors, this is one way to do it. If it were up to me, I wouldn’t do it. But it’s also a way of documenting things, how I work, my studio, the progress of pieces. I can understand that’s interesting for some people. Stone carving is a thing of commitment to work, so I don’t think about stopping to take a photo.

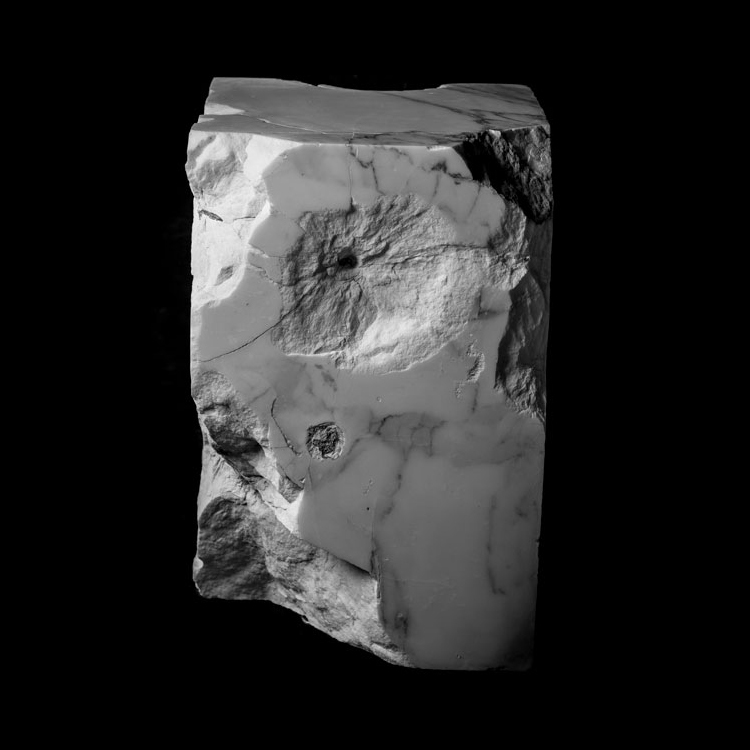

Would you describe yourself as an artist?

I prefer to be addressed as sculptor, as opposed to an artist. The term artist is too vague and too many people have abused that term. There is also this issue of the philosophical definition of what is art, and I don’t want to give a definition to that. What I know is I make sculptures. I’m a sculptor. It’s very easy to define that. I work with a block of marble and tools so I can fairly 100% say that I’m a sculptor.

Share article