From Babylon to the Banks of the Arno River

An interview with Erfan Rashid

Papers of Dialogue

June 2015

You were born in Rome, but Florence is the city where you had your first contact with the world of art. What does Florence mean to you?

Florence, from that point of view, is very Important because it unconsciously had a tremendous effect on me. Having grown up here, when I was young, I would exercise on my own drawing the city’s statues and visit all its museums. With my parents both being painters, for me it was normal to draw. I loved to draw the statues around town and they greatly influenced.

You are the son of two painters, the nephew of two painters and of another uncle who is a poet, since both your mother and father are painters, two of your uncles are painters and another uncle writes vernacular poetry in Iraqi dialect.

l didn’t know that about my uncle.

Your uncle Ali, on your mother’s side, writes or, used to write vernacular poetry and your other uncle, on your father’s side, works in the theatre. You first chose music and you became a good pianist but then, at a certain point, you made a 180′ degree turnaround and opted for sculpture, choosing a material, marble, which is pretty hard for the hands of a pianist .

Music has always been a passion for me: I grew up playing the piano. I studied the piano for almost ten years. But, at a given point, you must stop and ask yourself: what do you want to do and what are your objectives in life. To be honest, my musical aims were a bit too high to be achieved with my limited talent: I had to really make an effort to only achieve mediocre results. But, as I grew up in a family of painters, for me painting or drawing came naturally, it did not require a technical effort and it all came natural to me. I was always subconsciously aware that it was something natural and easy for me. Then it took me two years to decide to abandon studying the piano, because I didn’t know how it would end up for me. And so, I took this different direction.

You probably know that when your father first came to Rome, he came to study sculpture…

Yes, sculpture, at the Academy with Emilio Greco, if I’m not wrong.

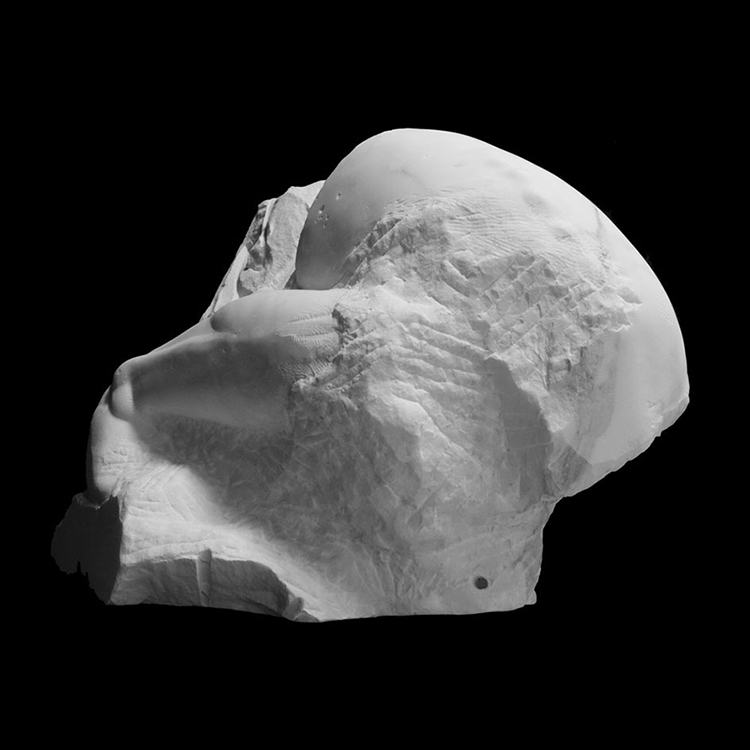

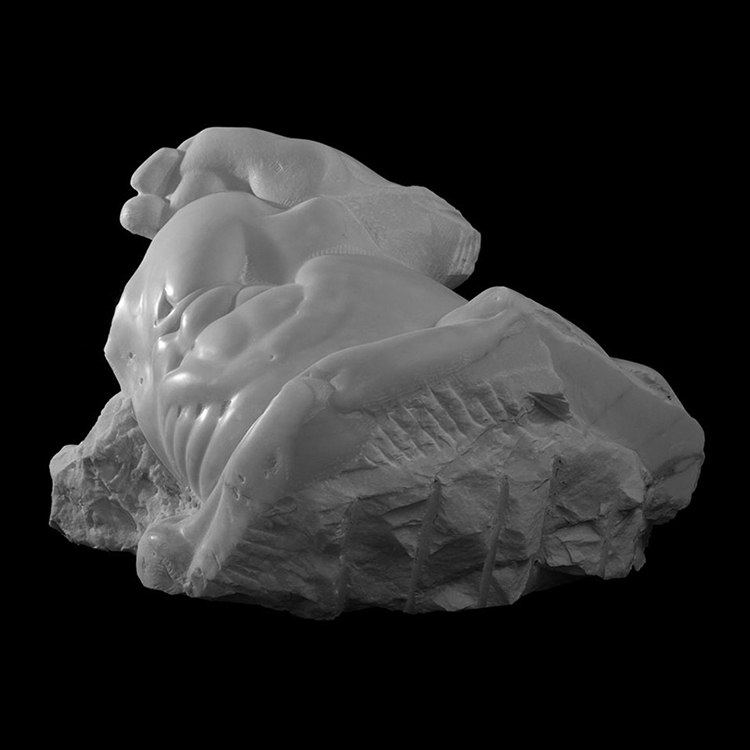

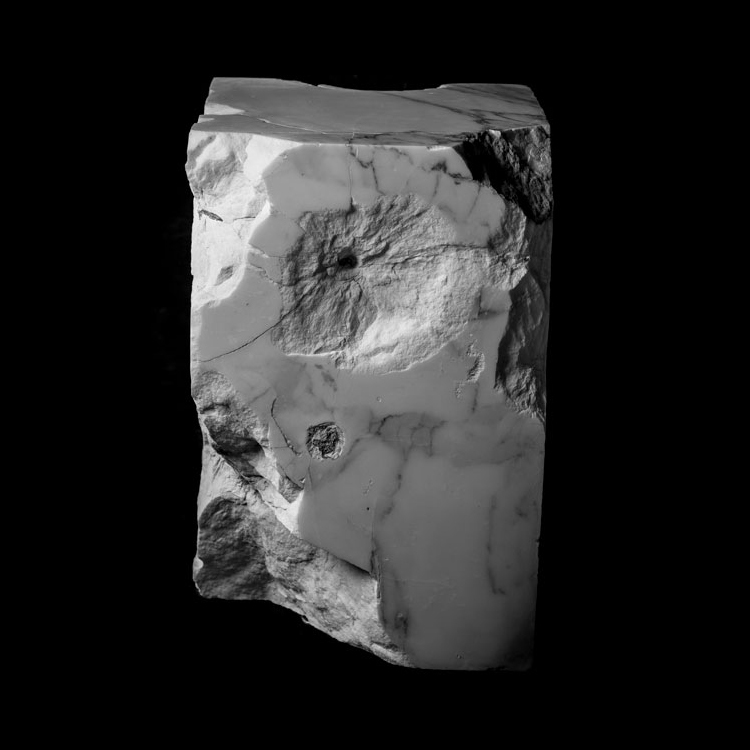

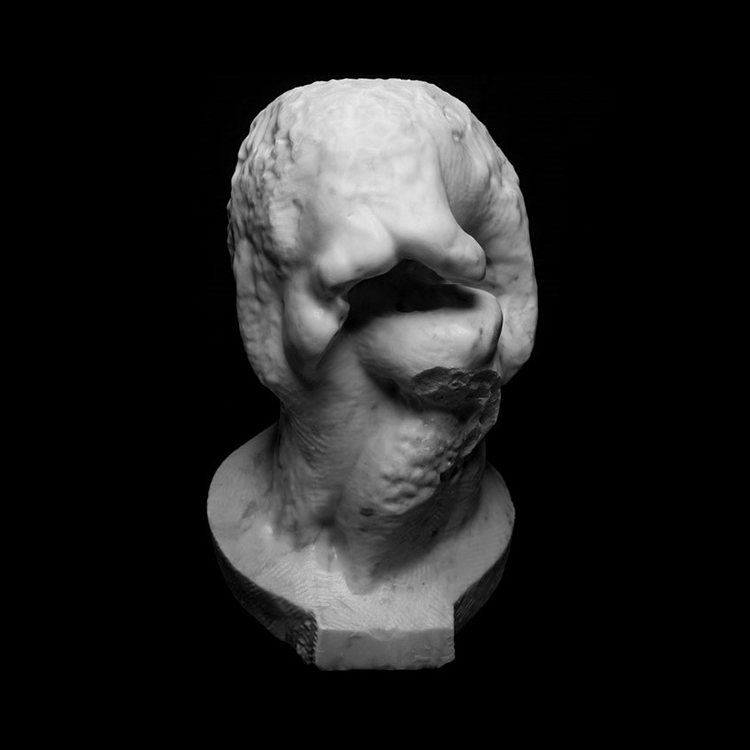

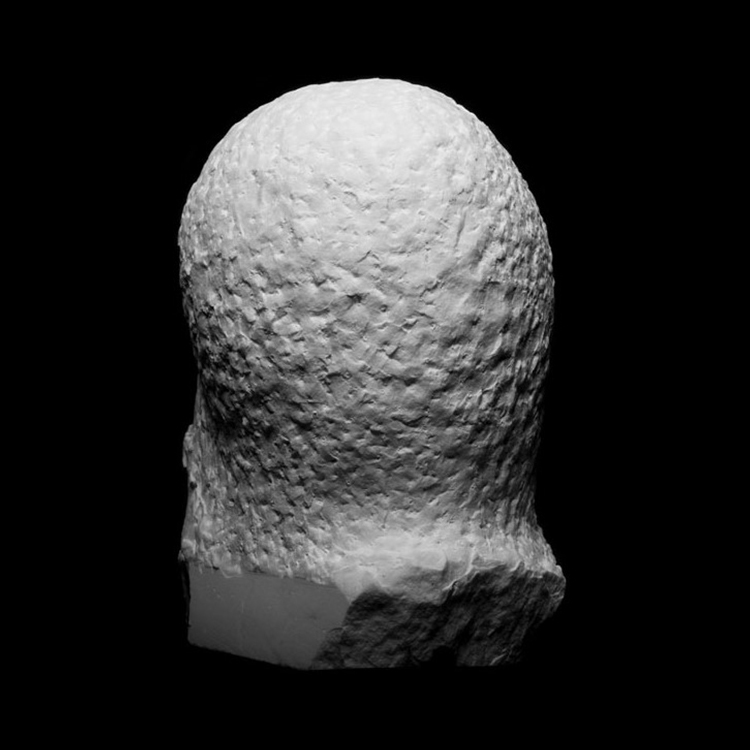

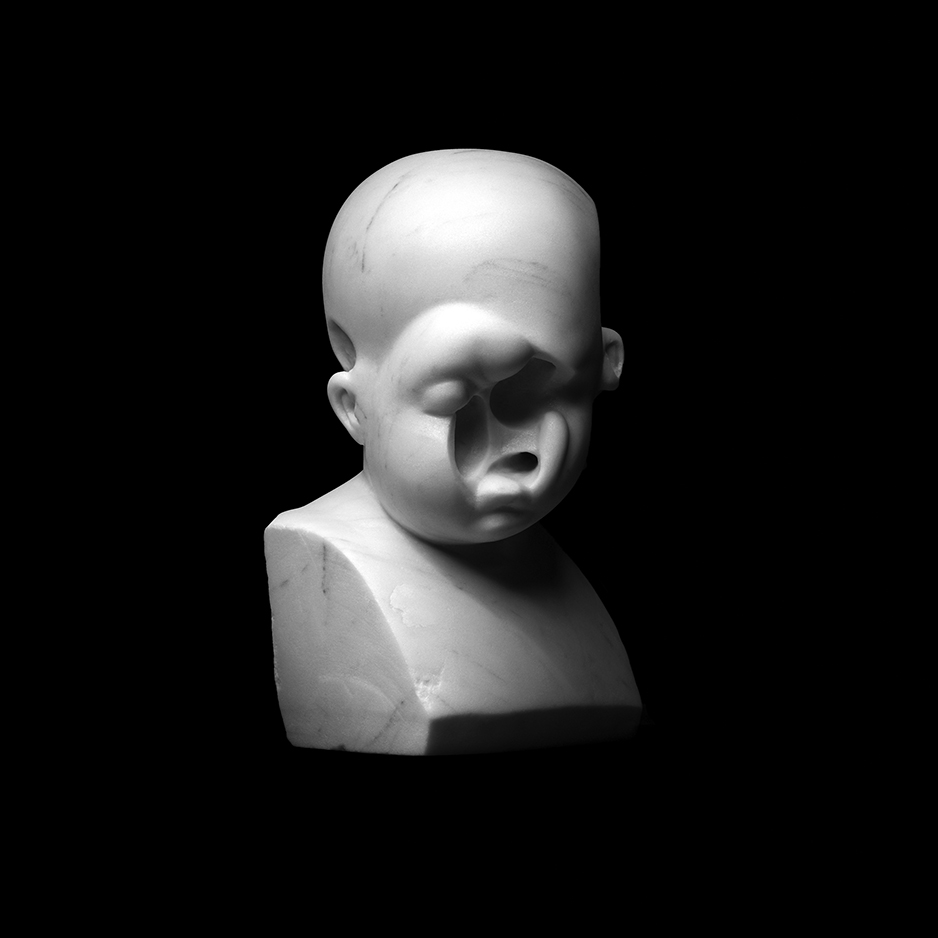

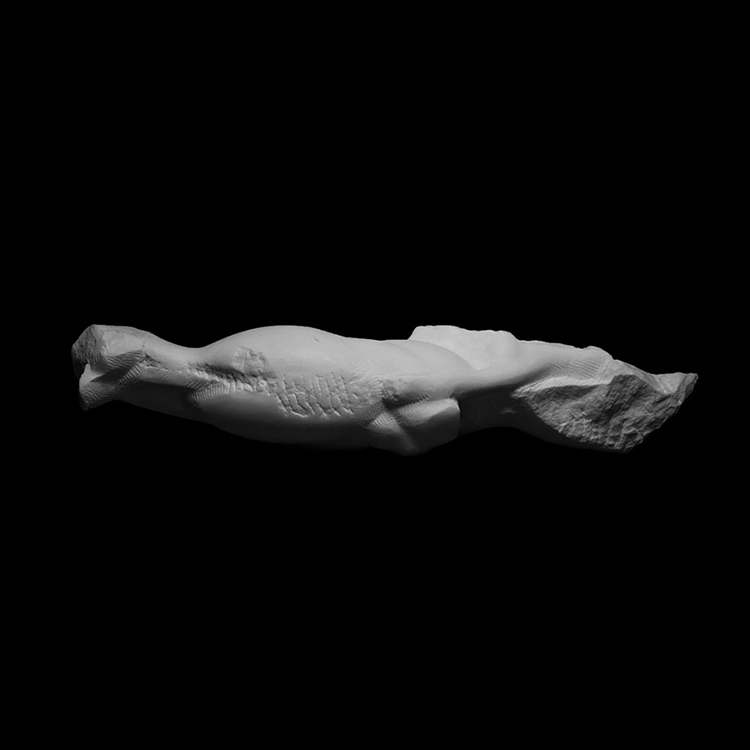

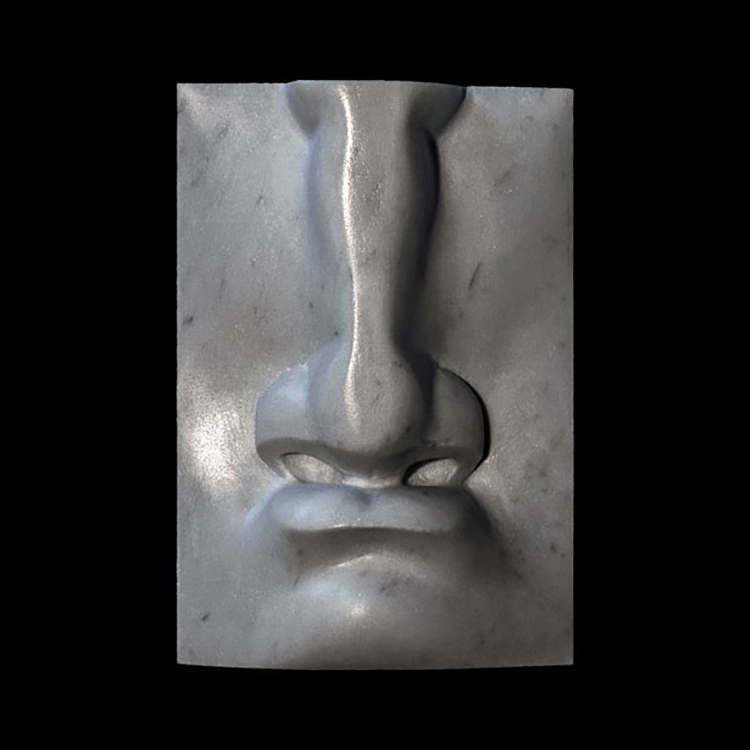

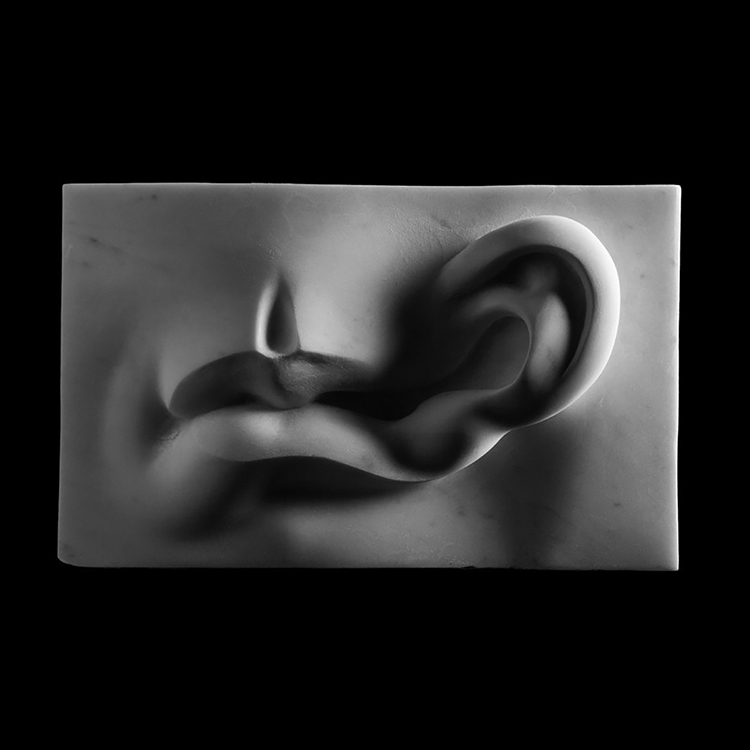

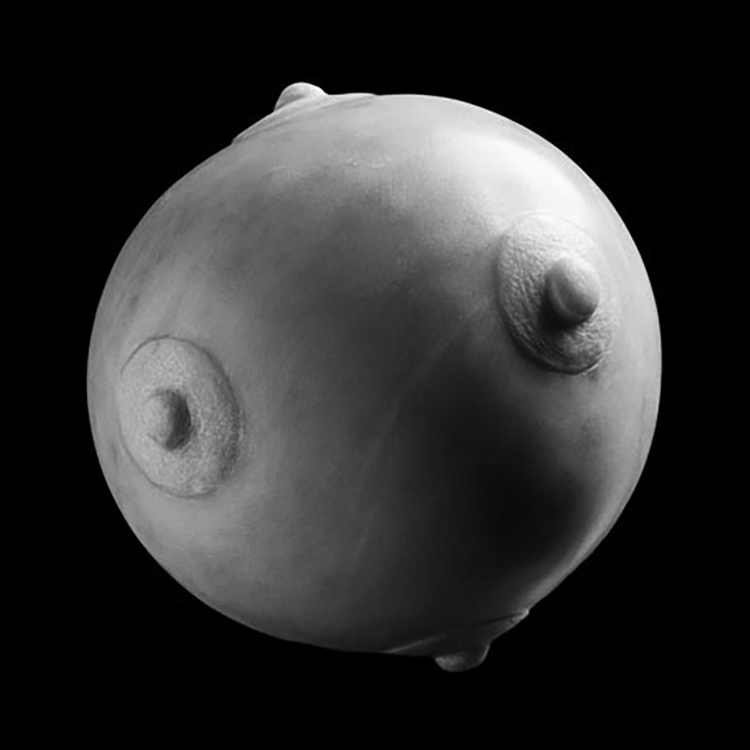

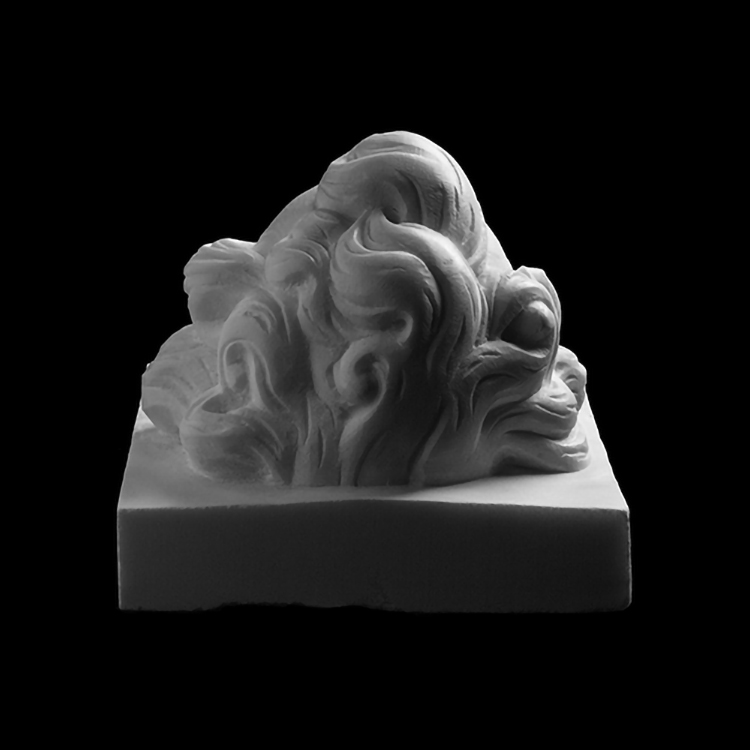

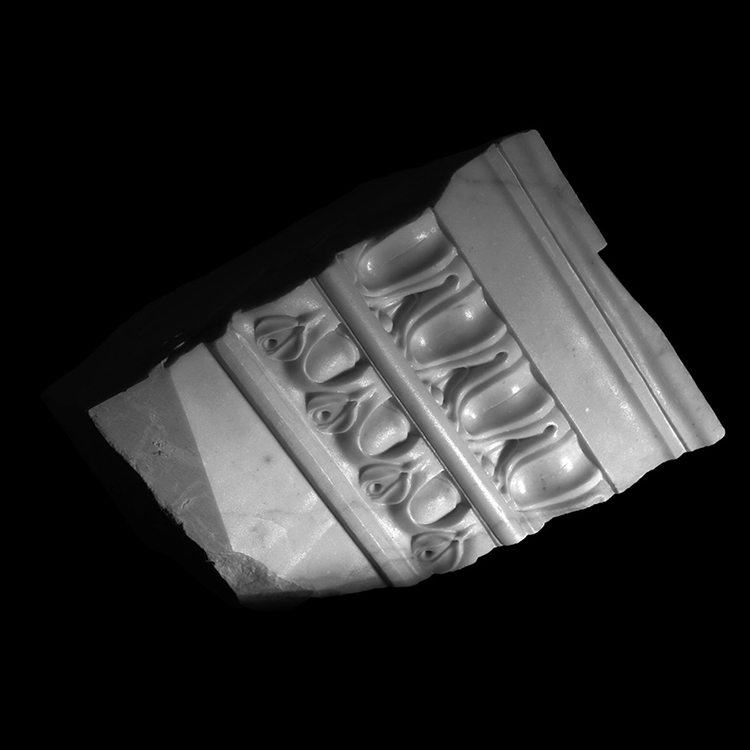

You practically grew up only a short distance from Michelangelo’s Pieta. Many of the sculptures that I’ve seen pictures of seem to be a rough hew growing out of the block marble. Is this by chance or by choice?

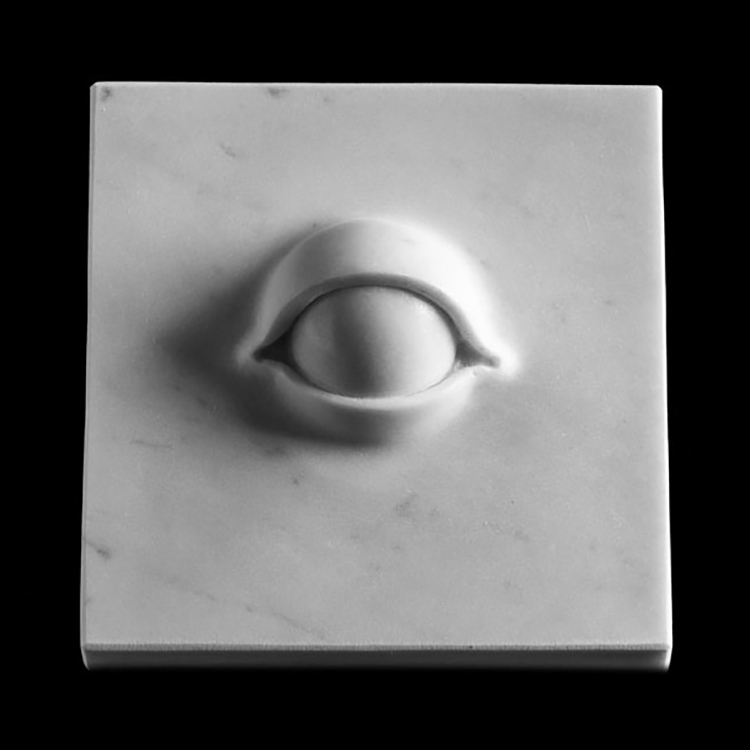

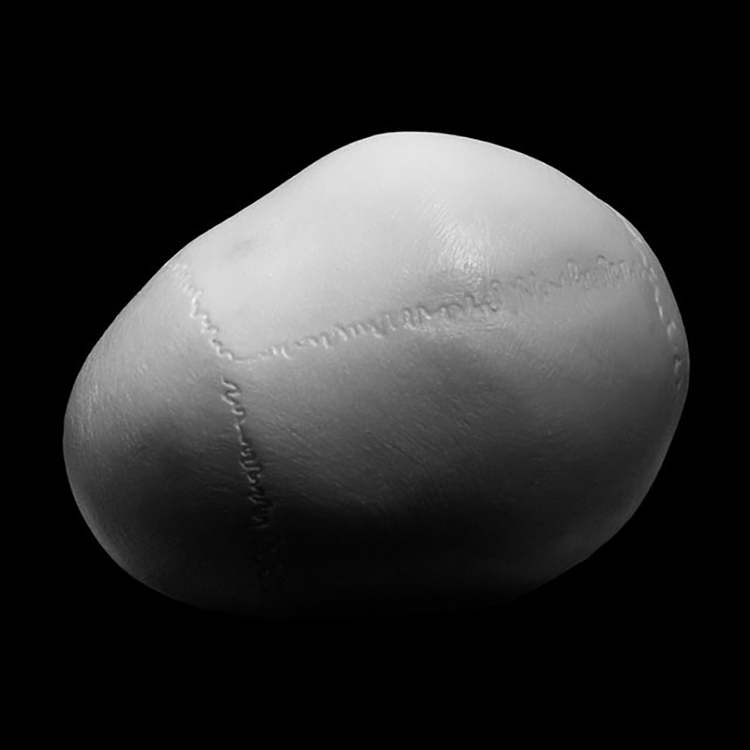

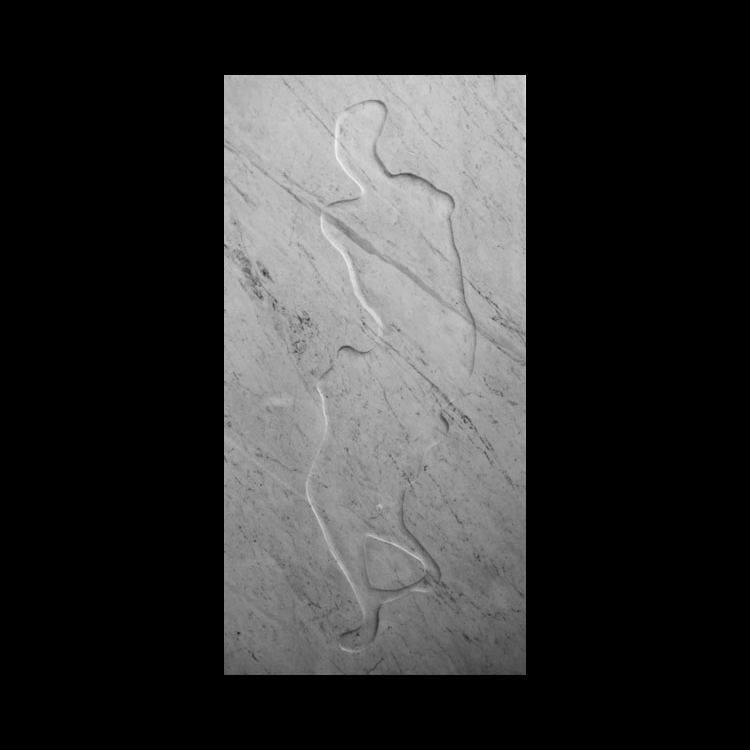

No, not at all by chance. It is a choice. As I told you, I used to go practically every day to the Academy Gallery to draw the David and I gradually became much more fascinated with Michelangelo’s Prisoners than with his David, precisely because they were roughly hewn and incomplete. If I have to be honest, the sculptures that you saw were created in order to give a contemporary interpretation of the same theme: the slave, the soul imprisoned or enslaved within the body or matter. I was trying to express myself beyond the material, in contemporary terms. And then there is the theme, which we might talk about later too: the aftermath of the war, of the suffering in Iraq, of my Iraqi past, which is a humanly universal theme.

You experienced your Iraqi past through the stories suffered and told by your parents and your friends, like all young people of your age. But you added an extra element: that of the erring migrant because you are with no fixed abode, we can say. You were born in Rome, then you grew up in Florence, then you went to Belgium, then to the Netherlands, and back to Florence and you travel back and forth from all parts of the world. In this case you are more like your father than your mother. What does it mean to you to be a wanderer?

It means not having a place you can call home, not having a mother-tongue as such to speak with ease and therefore it also means being accustomed to live in a state of uncertainty, which, by the way, is not a flaw. I use this also in my work and my approach to work: I err also when I shape marble. When I start something, I never know where it will end up.

Or, rather, possess all the languages…

Yes, but none entirely. Also possess all cultures, several mindsets, but again, none of them in full. Of course, knowing all these cultures enriches one’s general culture and one’s vision of the world. However, the thing I miss most is not having a home, a symbolic place to come back to. Obviously I feel at home here in Italy, it’s a place I fee l at ease in but I spent half of my life outside so I can’t really say I’m Italian, nor Iraqi, nor Dutch, who knows.

If I were to ask you what Iraq means for you, in very generic terms, because I think all of us have an inner image of Iraq.

Iraq for me is a combination of the Iraq we all know through the TV images, its recent history of dictatorships and wars and, on the other hand, through the stories told by parents, by friends, so very poetic stories about a gorgeous country. This is the country etched in my mind from the stories told my father and mother, by the pictures I saw of their youthful years in the academy: images of a very open, democratic country.

Our generation of Iraqis, the generation of your mother, your father and mine, feel very disappointed by this poetic Iraq now lost forever and never to be recovered. How much influence does this situation and this disappointment, which is no longer only passively transmitted to you as when you were a child, have on your feeling Iraqi?

You perhaps experienced Iraq’s darkest period, while living outside of Iraq. I lived it by seeing all the images of war and absorbed all the disappointment. Iraq for me is my remote country of origin but where I never lived in and I that never saw. I hope to be able to go back there to visit and perhaps also contribute to its cultural change. However, precisely in the light of what we were saying before, I don’t know if in the shoes of an Iraqi, a Westerner or a tourist. This is what remains to be understood.

Share article