A Curiosity

for Violence

An interview with Merel Daemen

This Surrounding Us All

March 2017

Athar Jaber

A conversation with a sculptor about his work and curiosity for violence.

Date of interview: March 5, 2017

Estimated reading time: 17 minutes

The weather was gloomy the day we planned our visit. It’s a drizzly Sunday early March, but the light is graceful and almost pretty in its glow. Photographer (Tom Peeters) and I met Athar in his home in the north of Antwerp. There we drank coffee and talked about the artist’s book and art collection. Facing the window, in the middle of the living area is an impressive matt-brown grand piano. The coffee is somewhat too intense for our delicate Sunday stomachs and so we, resounding with caffeine, find ourselves in our car following Athar as he drives towards his studio in the west of Antwerp. Athar leads us, as he hosted us, and indeed as he seems to do everything: distinguished, courteous, controlled.

We talk with the artist about the alienation he felt as a young child, the homeland of his parents, his heroes, violence, artificial intelligence, and his quest for freedom.

Both your uncle, your mother and your father are known painters. Growing up in Florence in the midst of such an artistic family seems romantic. Was that so?

No (laughs). Although not terrible, it was quite difficult to be a second-generation child. Not like the terrible images of refugees that confront us now, but there was a certain alienation that has shaped me. Italian was my first language, and I was born in Italy, but you have a strange name and ‘otherness’ that makes you a target for negative attention. As a teenager, it was romantic. From my early teens onwards, I visited daily the numerous museums and simply hung around the city to draw marble statues. I grew up with painters and artists around me, so drawing was easy.

After your parents left Iraq for studies, three successive waves of war flooded the country of your origin and your parents could never return to it as a result. How was that growing up?

When they left, they said goodbye to their family and environment for a short period. Then the war broke out. The Iraqi diaspora, a whole generation of artists, musicians, directors, writers who left to study in the 70s, have all been forced to leave their homeland behind. Those who were homesick enough to return haven’t survived. Some have been tortured and were able to flee. Some of them got a better situation, some worse.

Did you grow up with that sadness?

Yes. Even if you listen to older Iraqi music, you feel much sadness and melancholy. It is inherent to the culture. If you wake up in Italy as a child, with full knowledge of the facts and consequences of a war in the country where the rest of your family still lives, you simply have a different view of the world than your peers.

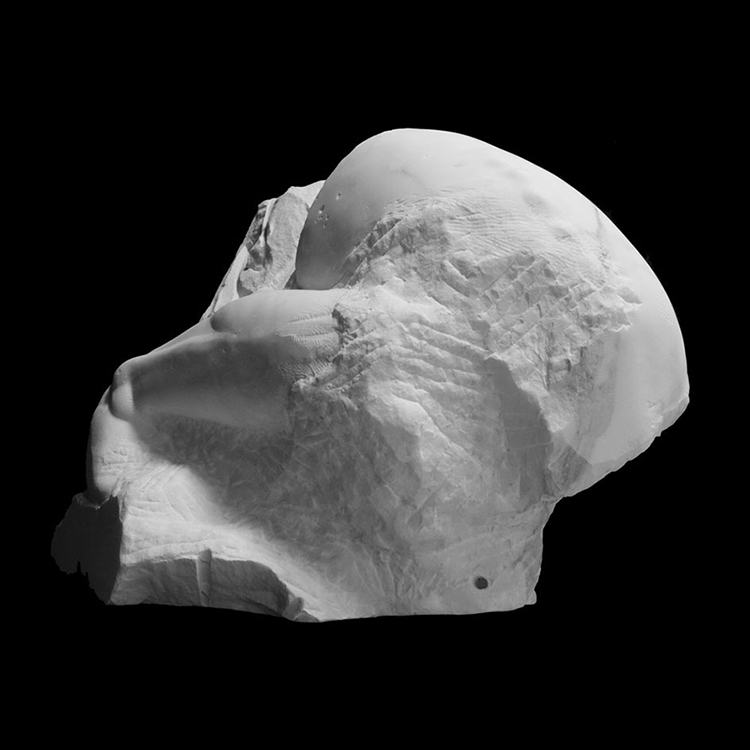

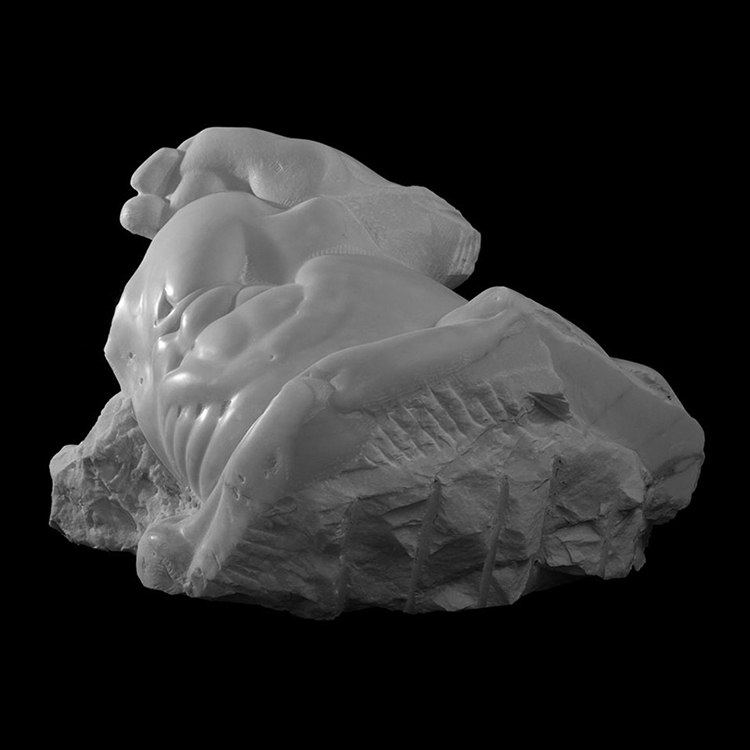

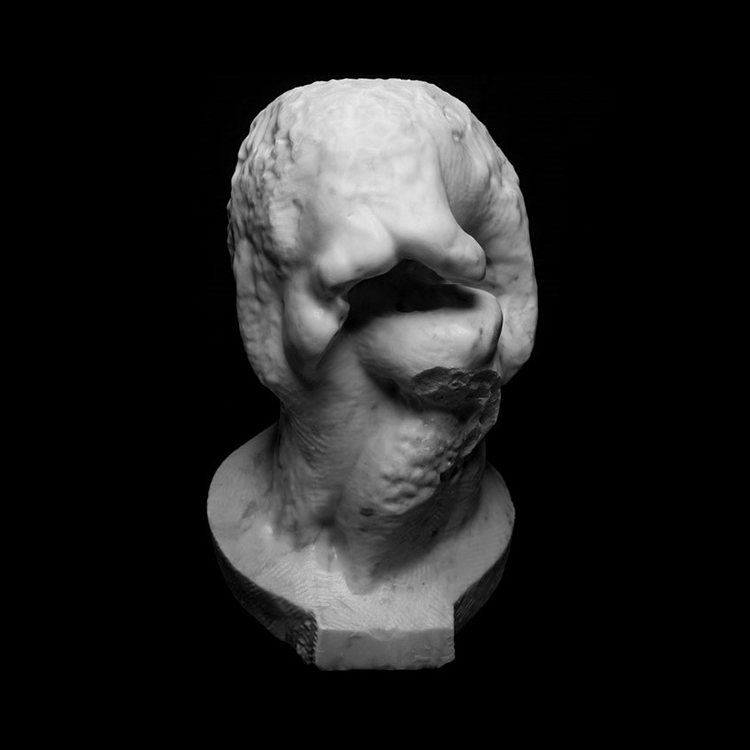

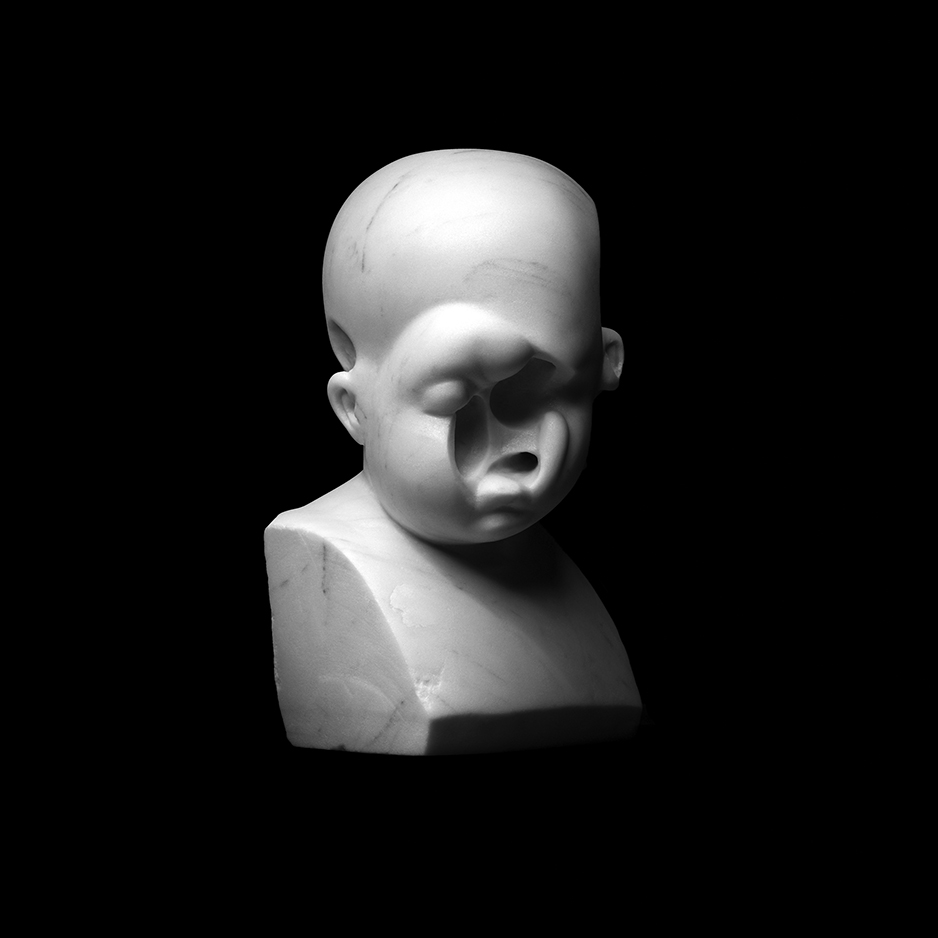

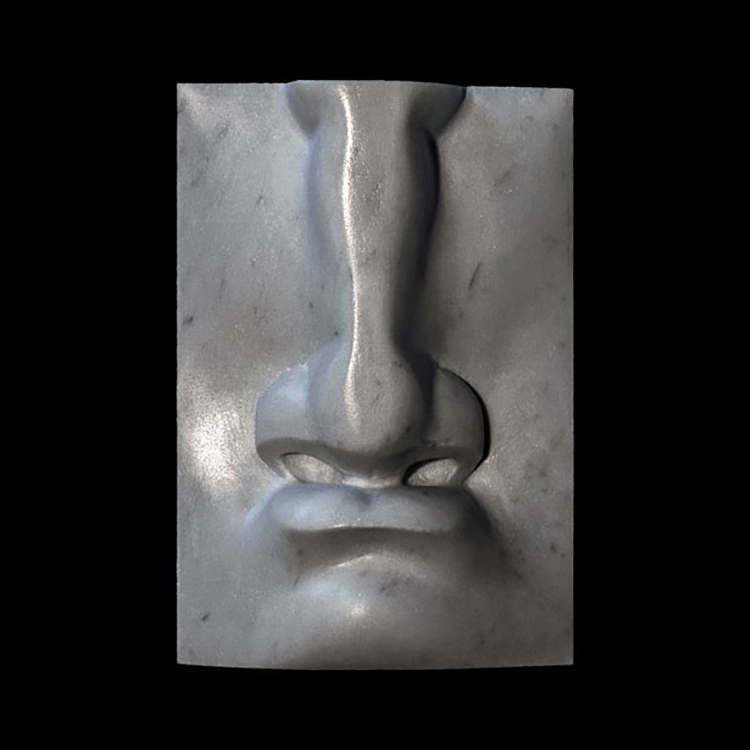

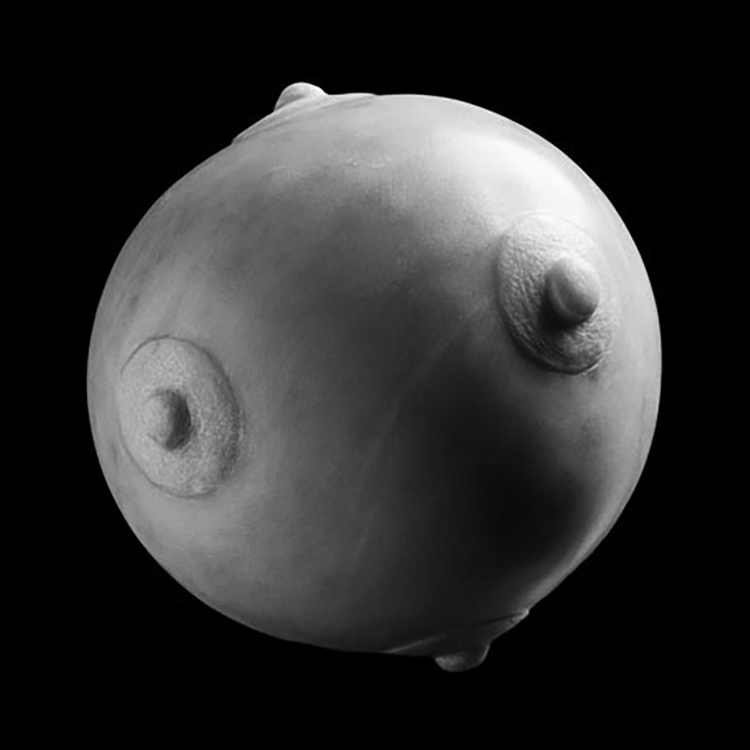

Your work has a bright, beautiful and light side. In your material, the anatomical beauty, the refinement of the result, I see examples of that lightness. But as a spectator you also catch a darker side. Is that derived from your past?

Content wise, my work settles closer to the dark side of life. The bodies and heads are unclear, ambiguous, distorted and broken. An identity crisis is at play. Who you are and where you belong are problems that concern me. The bodies and heads are unclear, ambiguous, distorted and broken. An identity crisis is at play.

You mentioned earlier in interviews that your national identity no longer affects your current identity, but you are mostly raised by an Iraqi woman who could never return to her homeland. I’m genuinely wondering how and where that distance starts and ends truthfully.

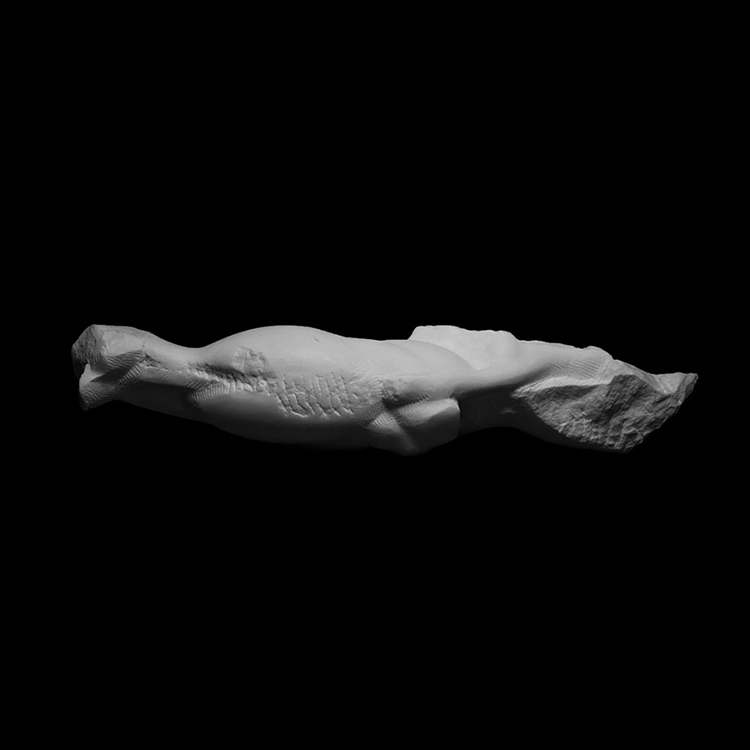

I obviously hate to see what is happening in Iraq. But by now, no more than when I see destruction, war or injustice elsewhere in the world. Syria, Tibet, South America, Africa. After a while you see universal connections and boundaries start blurring. The national parochialism doesn’t fit this time anymore. The world exhibitions, biennales and sports competitions, arisen to affirm boundaries in a healthy way, are also changed and the world has opened up. There are Algerians who represent Germany at biennials, people of African descent to play in European football teams. I really try to think beyond borders and time. In my work you will therefor find few references to time. No clothes, no objects, only the naked body.

The national parochialism doesn’t fit this time anymore.

You have previously studied piano. As a twenty-year-old you moved to Antwerp to study sculpture and have moved away from music. Why?

With pain in my heart I chose to become an artist. I felt I did not have enough talent to be the pianist I wanted to be. Because of my background I had more talent for visual arts than for music. It has taken me years to make that decision.

You refer to music in your titles. Your first four sculpting began with the title Opus 4, after which each respective image was given a number from 1 to 4. Does music remain to be a great inspirator for you?

I named those works with a wink to my previous study. People need names, but I do not want to force the spectators to see all things like me. I could have given numbers or codes as scientists do with stars. But indeed, music may still be one of my biggest influences to date. When listening to certain music, feelings just overwhelm you. Listening to John Coltrane’s later recordings gives you absolute freedom for instance! With my work, I of course want to appeal to those feelings. Important feelings, such as prostration, anger and freedom.

Now that you mention a certain ‘search for freedom’, your first sculptures come to mind. The four works of Opus 4, to me, seem ‘caught’.

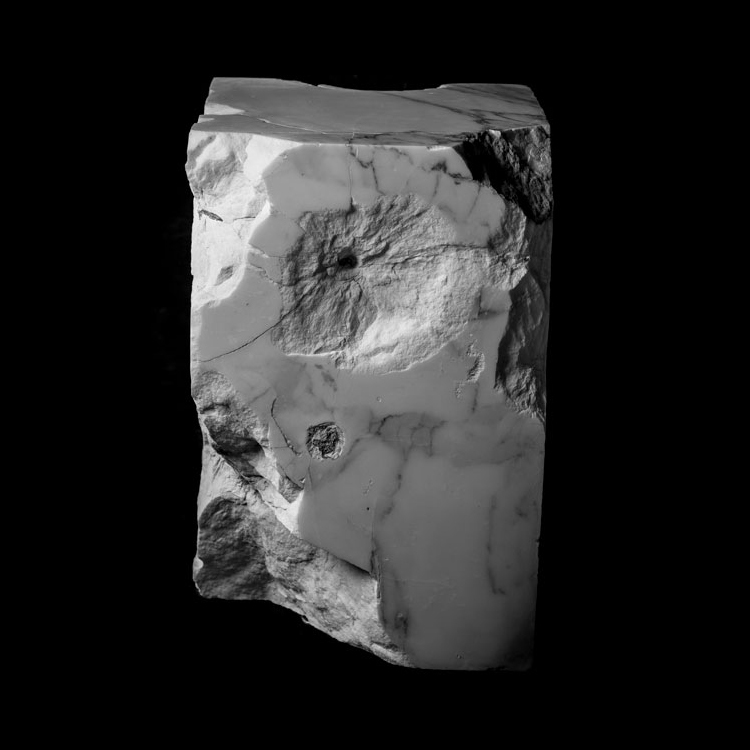

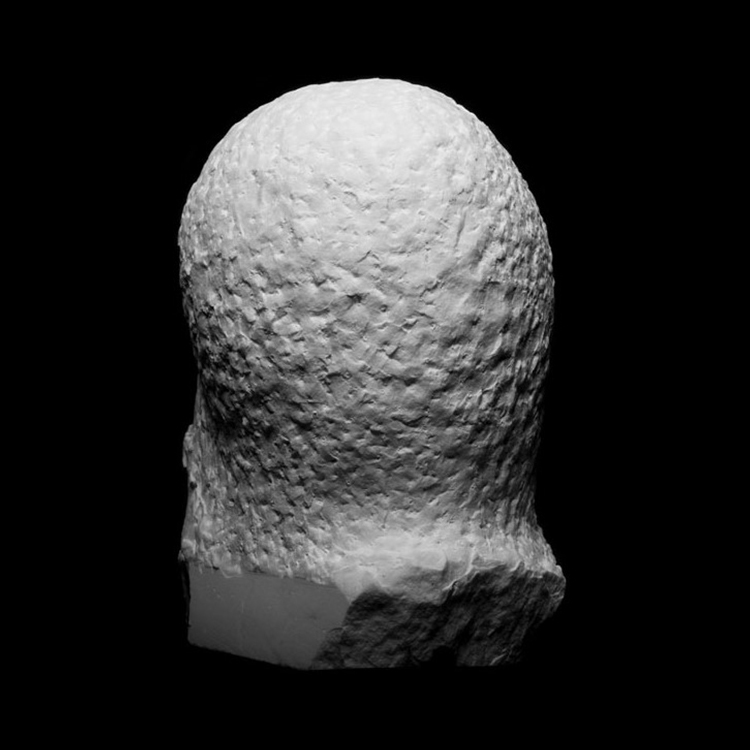

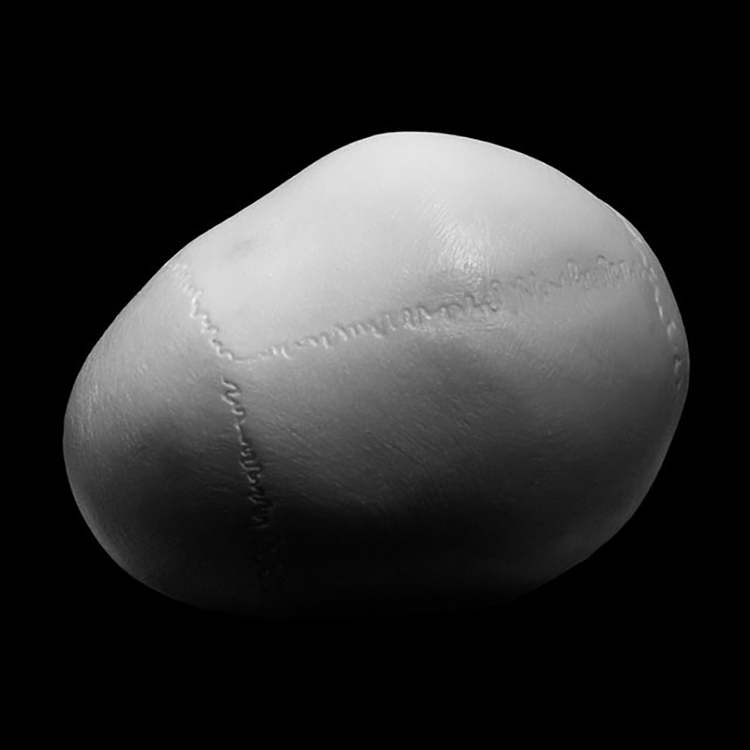

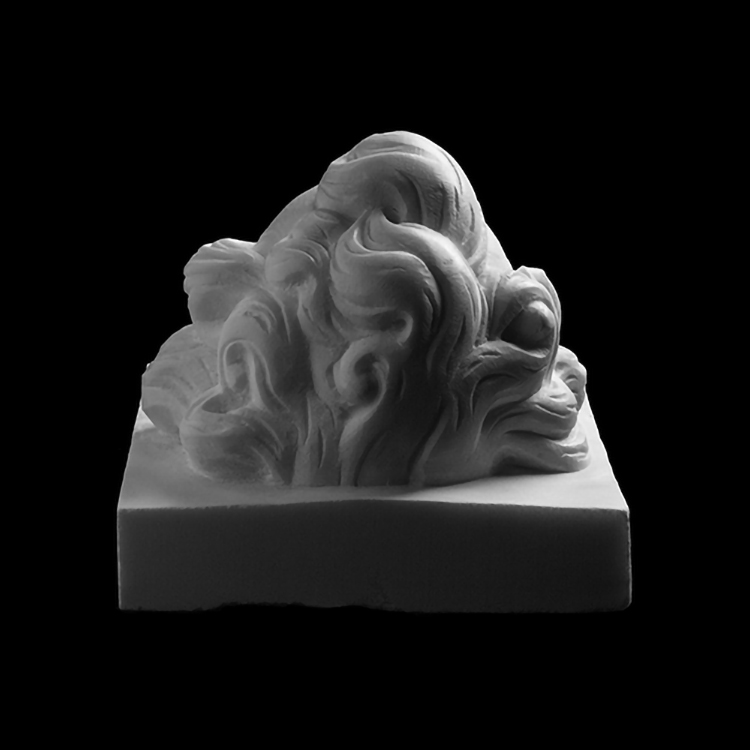

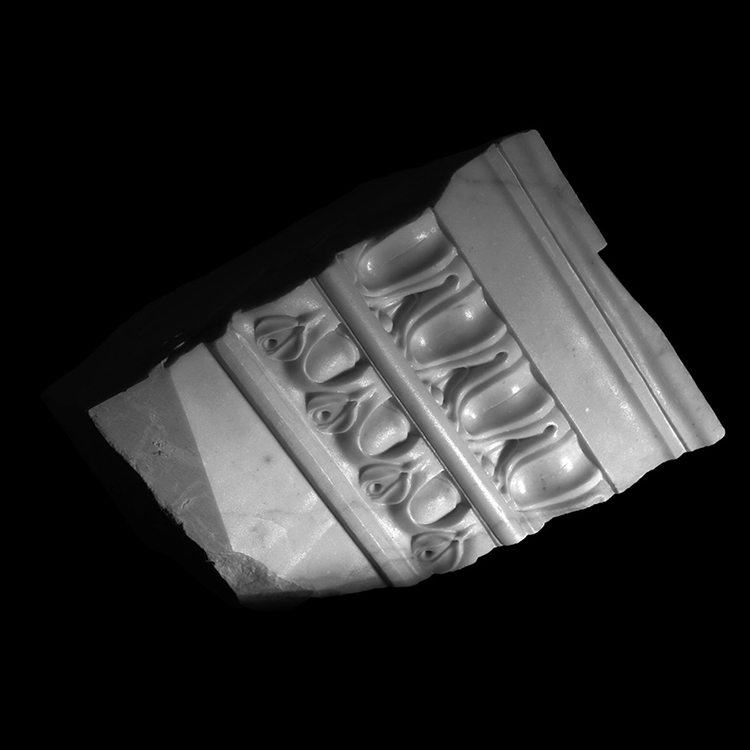

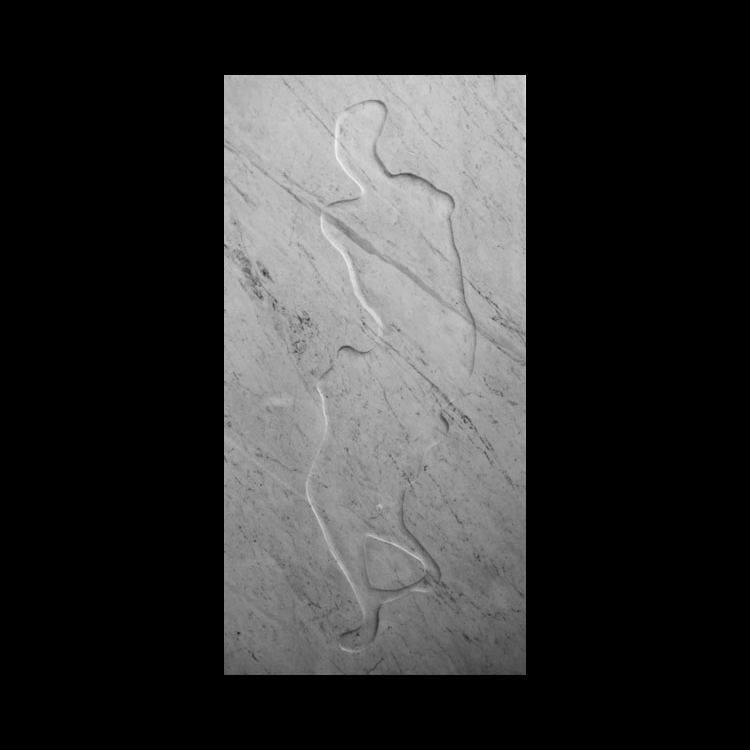

Every material has its spatial limitations. I chose to work exclusively with marble. In a later stage of my production, as in my main series (Opus 5), I learned to take more of an acquired freedom. This translates into technique as well as concept: drill holes, chisel tracks and broken fragments remained. Now I dare to let things go: put a sculpture in acid or shoot at it with bullets. I no longer chain myself to traditional sculpture techniques.

When I chose to study art, I instinctively chose this discipline. I didn’t doubt it for a second.

Why marble then?

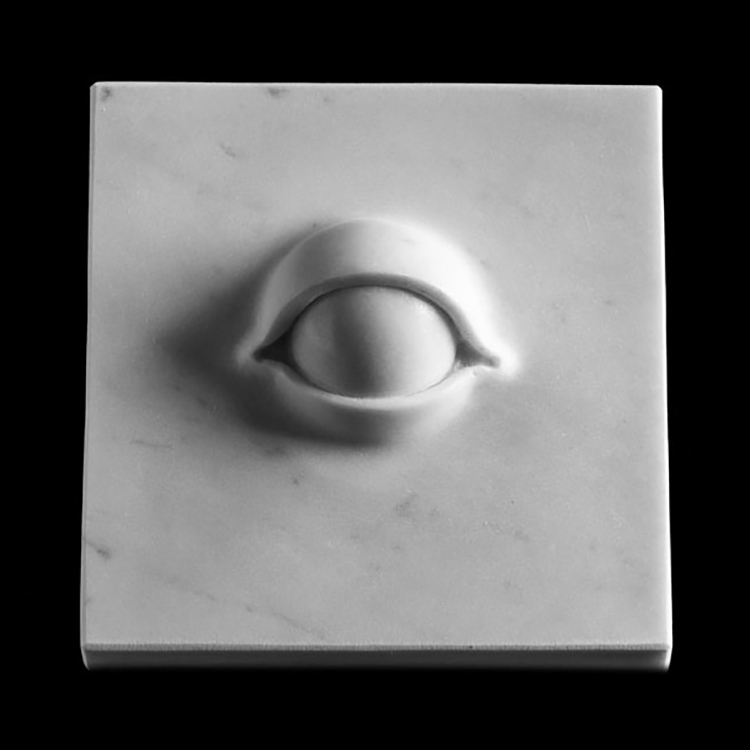

I think it’s rooted in my teenage Italian walks. Then and there a bond with sculpting emerged. You have a more direct and intimate contact with a sculpture than with, for example a painting. When I chose to study art, I instinctively chose this discipline. I didn’t doubt it for a second. Much later, I could explain this rationally: a sculpture takes up our dimensional space and threatens our freedom. It takes away space.

I produce my works directly in marble, they are improvisations. Most sculptors first build up something in clay or plaster and then put that image in marble. I am inspired by what is happening around us. A book, the light, the stone, my state of mind at the moment. It also becomes more personal this way.

Why do you still work according to the craft’s old techniques in a time of 3D printers and robots?

Exactly because of what I just stated! Many artists work with marble because it fits a certain classical tradition, and it is prestigious. Therefore, if you have the economic ability to make it happen, it can, indeed, be done by machines as well. But these artists are no sculptors. What I do is different. I myself work with the material and this action, which today is more and more rare, adds something to the work. It gives it another, almost metaphysical, dimension.

The reproducibility of the sculpture in these times has created enormous freedom for sculptors. Thanks to the technological developments, I can now express my emotion and thoughts in a more abstract way. I can be guided by my state of mind. How I feel at one point affects how I work on another. It is comparable to the moment in history that photography took over the task of painting. This resulted in the creation of abstract art, Dadaism, Expressionism and Surrealism, just to name a few.

So you believe in the aura of an artwork. What does that look like to you?

What impact does the way you make something have for the perception of an image? Creating a sculpture with your bare hands, hammer and chisel, calls for a different interpretation than when it was shot at with firearms and bullets. I sometimes feel a like a torturer. Hammering, chiseling, knocking and removing material with brutal violence while making something beautiful: it is a contradiction. With all I have experimented with other materials recently, trying to introduce the idea of patinating again. I only use “pigments” that carry a lot of meaning: wine, blood, crude oil, gold. But this is a new project, and I don’t want to tell too much about it yet.

What is it about art that attracts you as an observer?

I am often more moved by music. As an observer I approach art more intuitively and it is difficult to accurately identify what plays then. Last week I visited an exhibition of Cy Twombly. From books I never had a good idea of his work. Actually, if you want to talk about the aura of an artwork, he might be a good artist to discuss. His work really touched me. It must have been years since I was so impressed. In front of certain pieces, I was literally ‘resonating’. Probably because of what interests me at the moment. It was about violence. Mainly the series about Achilles and Patroclus and those about Commodus really moved me.

You told me that you want to get rid of the ‘marble block’ in a search for freedom. That, and some other things you told me, reminds me of a book by Hermann Hesse, about the encounter between the intellectual Narziss and the artistic Goldmund, also a sculptor. How do you see yourself in that regard?

I believe I’ve read that book at the right age. Of course, we always have both characters in us, but maybe sometimes one takes over. On the one hand, I create something that comes from inside, but there is also another side. I’m here for hours, sometimes working for months on one slab of stone. There are days that I don’t say a word. Certainly, in my performative works, where the aim is to reach a kind of meditative, transcendental state, I am much more the monk than the emotional artist.

Do you have a fixed rhythm?

I do not like busy places and in my limited free time I like to be at home. Reading, drawing, playing or listening to music. I would rather be in my studio day and night actually, but sometimes I have to rest. It’s physically heavy work. In addition, I have to divide my time between my other activities. I teach at the Academy of Antwerp, recently started a doctorate in the arts, am a member of the Young Academy in Brussels, and I often have to travel abroad for my exhibitions and projects. Those things must happen, and it keeps you going steady as an artist, but first of all I’m sculptor. I prefer being in my studio.

Being an artist is not a pastime, it is a luxurious but serious activity that carries responsibilities. It has to be taken seriously.

What are you trying to teach your students?

At the academy I teach ‘portraits’ and ‘stone sculpting’. Especially that last course comes down to hard work. I can teach them relatively little. In the end students have to do it themselves. I can only show them and give small tips. As a teacher I set the bar high. Whatever you do, you have to work hard. Being an artist is not a pastime, it is a luxurious but serious activity that carries responsibilities. It has to be taken seriously. I do not want to discriminate between expressions, anything is possible. It is important that young artists take their freedoms and develop their own language and not be influenced by the teachers too much. Many times I speak with curators and directors of museums and they often contradict each other. Ultimately, you have to decide what you want to do and go for it.

What will your doctorate be about?

It’s a “Doctorate in the Arts” that will develop over the next four years. It is practice-oriented so my artistic research will be emphasized and the PhD will also be mainly conducted in that language. It gives me the chance to be in the studio. As a sculptor you show the same violence as a torturer. My doctorate will deal with violence and beauty and the tension between the two. Removing material as a concept is already violent. If I take something from you, it’s violent. Taking stone away from a block of marble through hammering is quite a violent action. As a sculptor you show the same violence as a torturer. During the doctorate, I will develop and apply new techniques to remove material. Techniques that refer to other realities.

When I saw how Isis broke sculptures, I was appalled. In consequence, I decided to start using their methods for creating images instead of destructing them. For example, I want to drag a block of marble behind a car and see what that causes. It leaves behind traces on the marble and at the same time, I keep adhering to the classic definition of sculpture: to create by removing (material). Such and other similar actions will be developed and documented to investigate the relationship between violence, destruction, and creativity.

A recurring idea in your work is that the world automatically tends to disorder or entropy. What are your thoughts about this today?

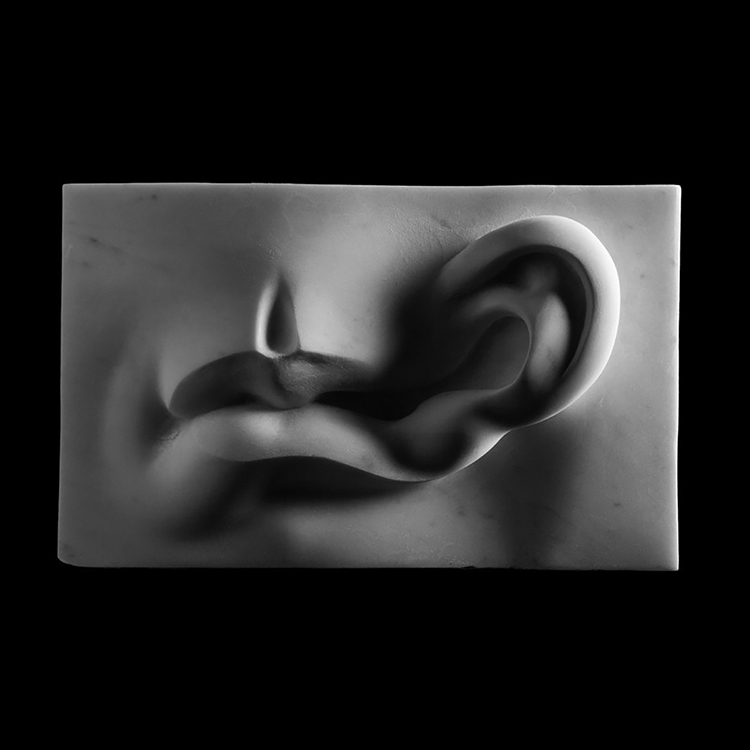

I can explain that best with music. An injury or deformation is similar to me to a dissonance. A dissonance occurs when two elements that don’t belong together are put side by side. A dissonance in music arises when notes do not belong together. It creates tension. You need moments of pause to recreate harmony. Harmony is a utopian ideal. However, as music history progresses, those dissonances have become more and more important and have prevailed. Music has become more abstract, and many loose their affinity or starting point with contemporary classical music. I consider this to be a metaphor for the concept of entropy. Like the stars in the universe always accelerating to further disassemble. In my work that translates, for example, in strange physical combinations, like ears beside a mouth, an arm ending in a foot, strange deformities, disorder, tension, blurriness, abstraction. Marble is relatively eternal, but we know that it also will eventually be pulverized. I want to prove that nothing is wrong with that. Learn to accept our finality and appreciate it.

So is working with an ‘eternal’ material an attempt to let go of your existential ‘angst’ of dying?

Disorder, or the metamorphosis to another state is natural. We do not give ourselves over when we say that’s okay. Death is coming anyway. That realization confronts me during the creating process. I try to gradually accept it and do something with it. Ultimately, it is the driving force that engages us all. I work with a material that stays “forever”, while I am aware that also the heritage of ancient civilizations is doomed to disappear. Isis or not. That confronts our existential life questions. History shows that murders and war are part of our nature. We shouldn’t welcome that but accept it as a hard truth and yet aim for a better harmony. Even though it is hopeless. To show this issue, I’m doing it myself, on marble, without too much impact on our world. Marble allows me to do so.

Are you a violent person?

We are all violent. But there are ways to channel this. If I take off material with a hammer and a chisel for hours and hours, I come across a kind of trance, and I enjoy it. That raises questions. Why does a human being do things like that? Sculpting is extremely physically heavy. In winter it’s freezing cold in here, my body and my hands hurt, it’s dusty and dirty, yet I enjoy every moment. I’m not just doing this for the result, I also enjoy the action. My body and my brain are addicted to it. Otherwise, you cannot keep doing it. I can’t just make beautiful statues. Leave that to some other artists and the machines. The question you asked about the new technologies and aura in art leads us to talk about the action and the human motive. Why do you do it?

In your production you choose for slowness, so that you can incorporate personal emotions into the stone. That’s your conceptual choice. A next step in artificial intelligence however is to create a being that will be able to imitate that more and more. Have you seen the “Westworld” series?

Yes. Have you seen the 1970’s film on which the series is based? It is darker, and simpler. You know there are already robots making art in an intuitive way? But A.I. cannot think independently yet. If that ever can, those will be other thoughts than ours. Now more than ever we must keep our humanity.

Interview: Merel Daemen

Revision English text: Gary Leddington

Photography: Tom Peeters

Share article