Nonsequitur

An interview with Esther Harrison

Coeur et Art

March 2019

How do you feel about your roots, the cultural differences you experienced in your upbringing and how are these influencing your works.

My parents come from Iraq, a country that I have never visited. It’s very confusing. While I have learned to live with this ambiguous identity, it puts other people at unease. They can’t place me, or anyone else with similar complex roots, in one specific box. People need certainties and clear answers, especially today when issues of safety and security are being capitalised by various institutions and fear has become a motivating agent.

It is an incredible gift to be able to claim affiliation with various cultures.

Sadly, nowadays an ambiguous identity is perceived as a threat, it generates tense situations. This is problematic. Given the relative ease with which people today can travel and start new lives in other parts of the world other than their native countries, a fluid and ambiguous identity is a phenomenon which is bound to increase in time. Until a few years ago, I felt closest to Italy, the country where I was born and spent the first half of my life. But now even that certainty has blurred out. I speak five languages but don’t master any of them entirely. It is a phenomenon that made me question the concept of national identity. I believe that the general need to feel affiliated with one specific country is a limiting concept. Borders suggest the threat of violence. Regardless of the implicit problems, considering myself liberated from feelings of national pride and belonging, I attempt to look at a larger image and reflect on more universal issues shared by humanity as a whole.

The human condition, characterized by violence and decay, is a theme that is taking much of my attention lately.

If unpacked, this interest encompasses various disciplines that range from politics to religion, economy and social sciences.

My first emotions when I looked at your work, were a bit uncomfortable, as It felt so real and familiar, I wanted to touch and feel the cold „flesh“, but the stretches and cuts created a nearly physical pain and shock. If you would describe your work to a blind person, who can only feel them, what would you tell them about your approach, meaning, longing?

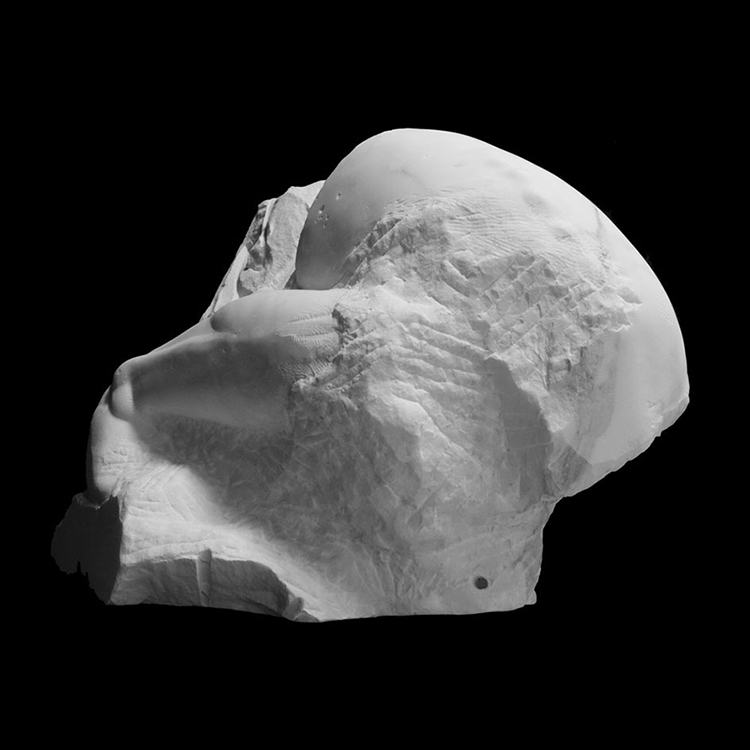

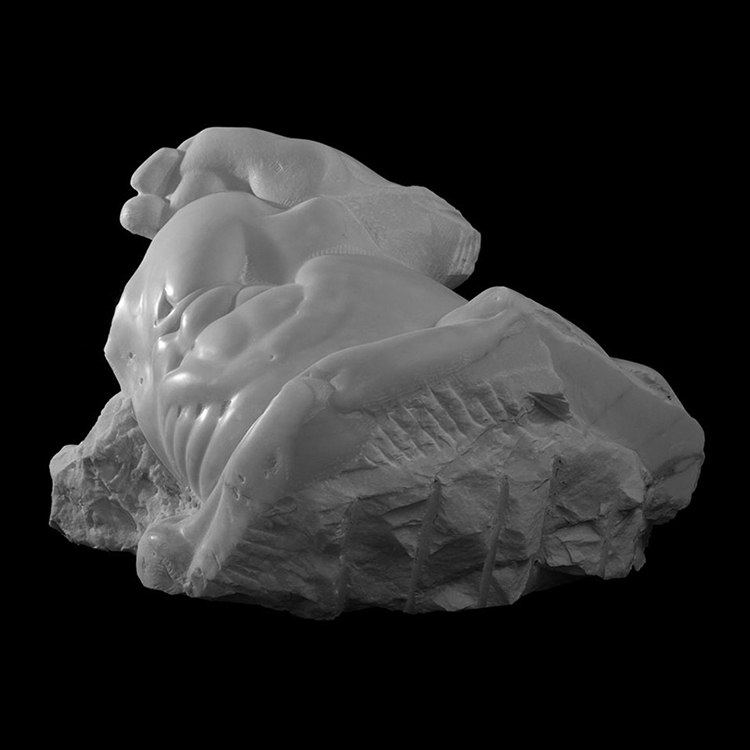

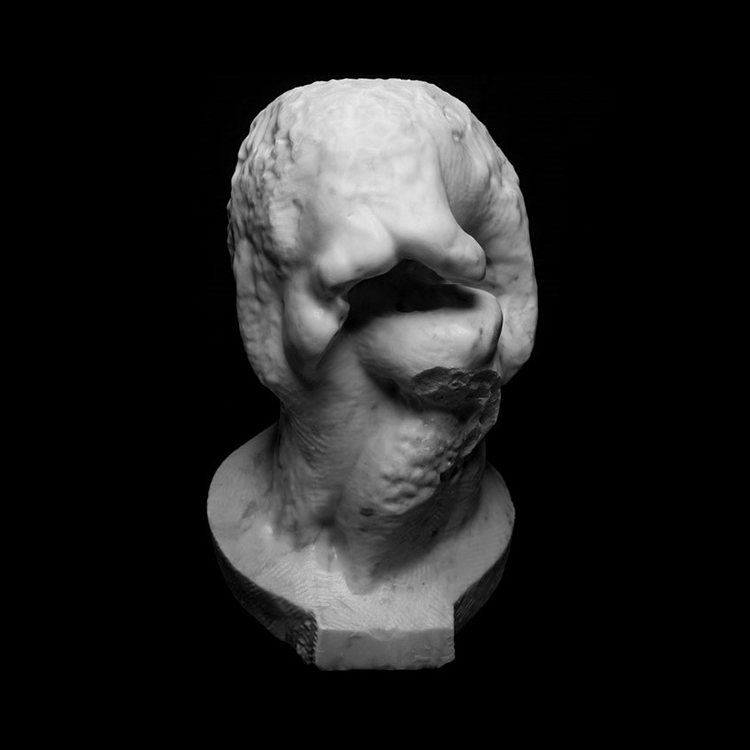

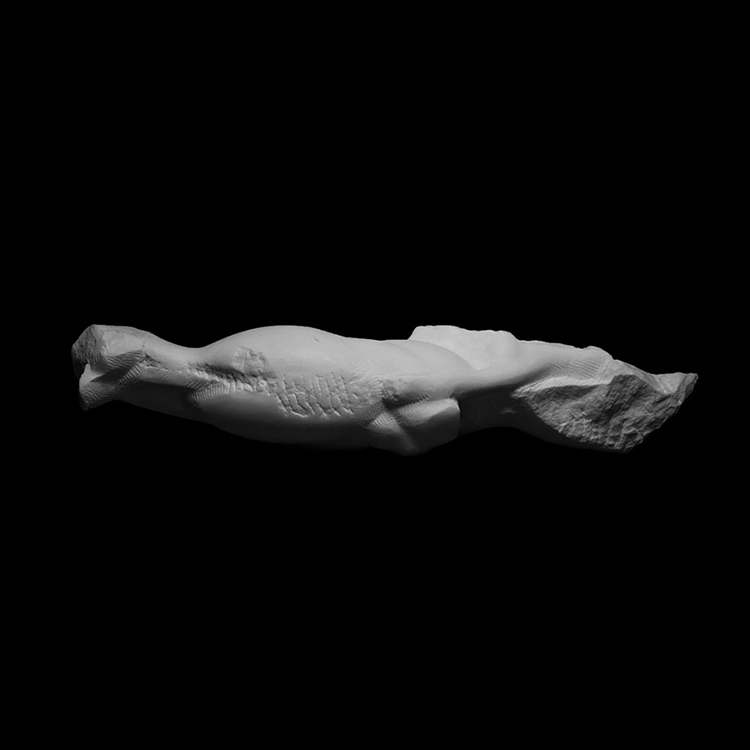

The Louvre in Paris has a room full of cast copies of its sculpture collection. The casts can be touched, allowing blind people to “see” the sculptures with their hands. The last time I was there, I noticed a blind man who was gently passing his fingers over the face of a sculpture, examining its idealised features. He was entirely focused, leaning towards the statue, with his mouth open, in awe for being able to connect in such a way with an artwork. It was one of the most moving interactions I have ever seen of a person, blind or not, engaging with a sculpture. I always allow my sculptures to be touched. In contrast to the idealised beauty of classical sculptures, my works are often broken, fragmented, distorted. I believe that the integrity of the human body is not suited anymore to represent the condition of contemporary society and its current state. Instead of referring to a parallel, “platonic” world, where concepts are distilled to perfection, I am more interested in addressing our own reality. And as we know, it is a much more complex and harsh reality.

Lenin once said that ‘the aim is to be more radical than reality’. While Francis Bacon said: ‘What could I do to compete with the horror [of life] that’s going on?’ I’m trying to find the sweet spot in between.

Human endeavour consists mainly of endless attempts to constrain or delay an inevitable entropy. Politics, economy, religion, with all their complex and controversial mechanisms, are all primarily aiming to avoid society’s descent into chaos. Damage control. But the damage is nevertheless clearly visible. Buildings fall apart, infrastructures need to be maintained, deforestation, pollution, and the list go on. Not to mention the damage that is being inflicted on a less detectable level – psychological, environmental, etc. – by less visible agents.

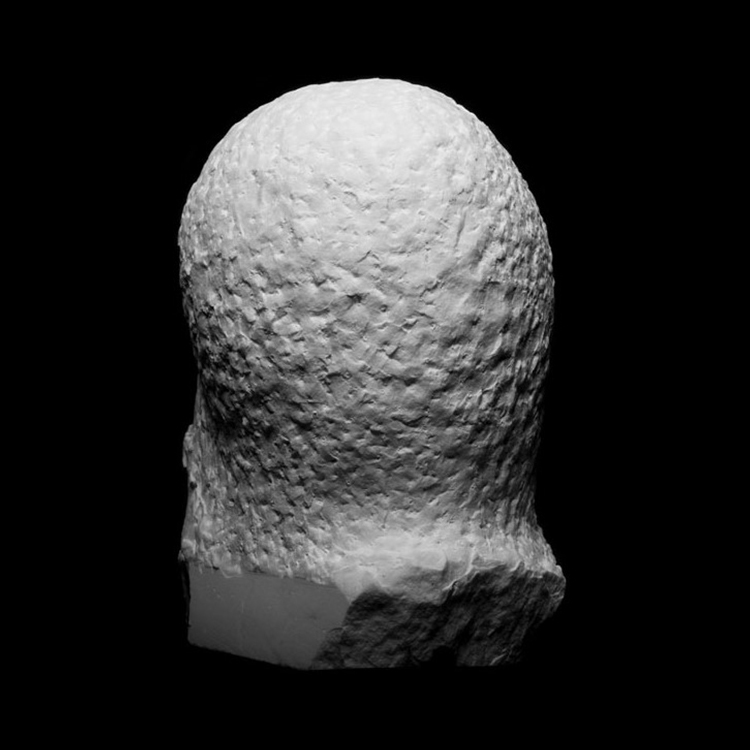

In the works you are referring to, I intended to mention these kinds of damage, directing the attention to the scars as testimonies to suffered injuries, metaphors for more complex discourses. Sculptural portraiture was probably the most important and original contribution of the Romans to the visual arts. In contrast to the Greek ideals of beauty, the Roman Republic introduced a realistic representation of important men, accentuating the asymmetry and all other signs of old age such as wrinkles, loose cheeks, baldness. They perceived these as testimonies to a long life lived in full. Equivalent to experience, wisdom and dignity. What a contrast with today’s fear of ageing, hopelessly countered by drastic surgical attempts.

What feeling and concept would you want to stay with the „viewer”?

Generally speaking, I try to convey a positive message, even though my works are often interpreted as dark and pessimistic. I often refer to the subjective and objective violence, ubiquitous in human conduct. On a larger scale, the same behaviour is also observable in nature. Violence (which at this stage can be perceived as a subjective bias), entropy and decay are inevitable, maybe even essential components of life. The sine qua non to life. By pointing to this certainty, my attitude is one of acceptance, carrying on, trying to make the best of what we have. I firmly believe that the concept of beauty should not be merely limited to a sensory experience. I see beauty whenever an idea is delivered successfully. Musically speaking, a dissonance, which is acoustically unappealing, becomes beautiful when it stands for inevitable setbacks. In fact, it is the only way to adequately address these crucial moments. And by the way, a harmonious resolution is incredibly satisfying when preceded by a dissonance, which makes the latter a necessary ingredient.

You are holding a position as an Associate Professor. Is the changeover from being an artist to a lecturer, a professor and researcher, something that came naturally to you, like a logical thing to do and what do you teach besides technique to your students?

I teach stone carving at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine of Arts. Teaching does not come naturally to me. A lesson takes a lot of effort and preparation. Besides, a teaching position nowadays carries burdens that undermine the original intentions of the noble task of passing knowledge to a younger generation. I am referring to the endless regulations underlying the educational system that puts teachers in a more bureaucratic position than anything else. It is a very sensitive topic, especially when discussing educational policies related to the arts.

Academicism has almost become irrelevant in contemporary art.

Consequently, there is little left to teach that is quantifiable within limits of grades. Since art is one of the few fields where subjectivity and intuition play an essential role. Furthermore, because artists are supposed to adopt an inquisitive attitude towards their environment, questioning and challenging previously set norms, an art academy assumes a paradoxical role. Like parents who attempt to educate their kids according to their standards and beliefs while telling them at the same time to be more rebellious.

Maybe the only thing one can teach nowadays in art academies is precisely this attitude of inquiry and challenge of the status quo. But students learn by imitation, so teachers also have the responsibility to set a valuable example, backed by an attitude of work, curiosity, passion and commitment to one’s profession.

You are exhibiting around the world. Is there a place you feel your work responds or clashes in particular?

Whenever I exhibit in a specific place, I try to adapt to the context of the country, to engage in a dialogue with the local culture. I like presenting alongside permanent displays of museums, like in the case of my solo shows at Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence in 2015 and at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana that just ended. In both cases, the juxtaposition resulted in a synergy that recontextualised both parties and allowed for a different reading than the usual art-historical one. In the first case, twelve of my marble heads were exhibited next to the Medici-Riccardi collection of Greek and Roman portraits.

The “damages” that characterise my sculptures allowed for a new reading of the actual damages suffered by the ancient paintings, now perceived as a sculptural representation of real bruises and scars or as medical pathologies.

In the latter case, my latest series of sculptures were exhibited next to the museum’s collection of Dutch and Flemish masters. Many of the works I presented were thematically informed by Afro-Cuban religious practices of sacrifice while being aesthetically inspired by the selection of the museum. I attempted to make associations between the two, highlighting details within the centuries-old paintings that often go unnoticed. The result was a dynamic exhibition that revitalised the museum’s collection, presenting a dialogue that spoke both to the local community as well as to the contemporary art world.

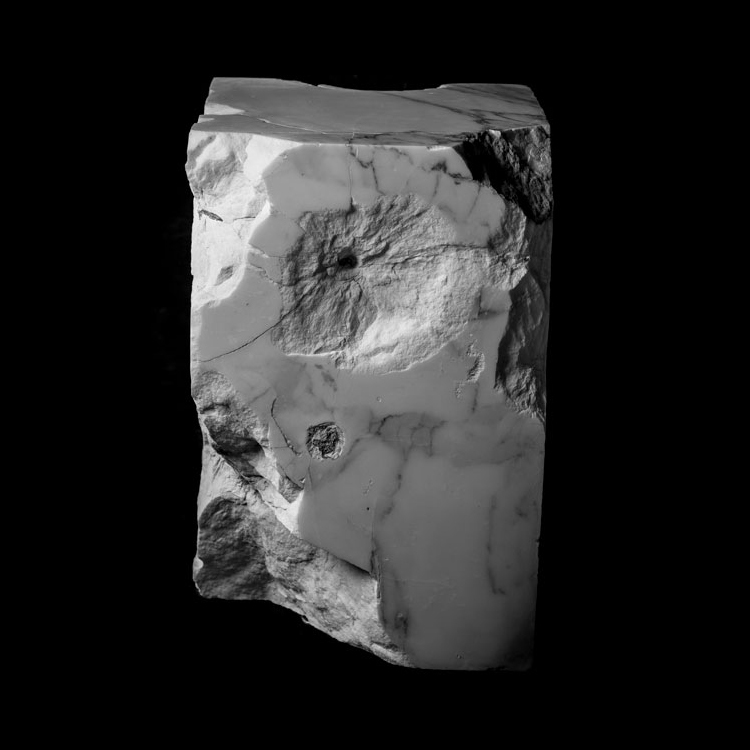

In 2017 I was invited to a residency in the little town of Birzeit, in the West Bank, to create a sculpture for the inaugural exhibition of the Palestinian Museum. It took me several weeks of research and immersion in the local culture and its difficult condition to come up with the idea that could speak to it. I found the answer in old Jerusalem, a problematic location, worshipped, contended and abused by various communities. The city’s stones being at once the unifying and dividing factor.

The museum exhibitions and the residencies are active approaches that allow for enriching dialogues with other cultures, both in space (Palestine and Cuba) and in time (juxtaposition with ‘older’ art). I am very fond of these interactions. All these experiences made me realise that if this is a clash, this is to be found between the societal fabric of a community and the somewhat “elitist” art world. And within the latter, another clash can be seen between cultural driven art institutions such as museums and biennials and economic driven commercial institutions such as art galleries and fairs. It’s a problematic relation as the conceptual discourses dealt with by cultural establishments are often conflicting with the economic goals of commercial practices. But there are exceptions, as proved by international artists who can tackle problematic themes while being successful in both the cultural and commercial realm.

Tell us a little about Berlin and your exhibition, you will show with Juliette Bartoli, what kind of work did you pick and why?

In a sense, this exhibition is another interlocutory exercise with another visual medium such as painting. Juliette and I owe a lot to the aesthetical depictions of the human body as portrayed by ancient civilisations. Greek and Roman in this specific case. We both apply a similar visual methodology – the fragmentation of the human body – while exploring different topics. Juliette is interested in epistemological theories, especially regarding the structure of language, semiotics and how meaning is formed. Whereas my works tackle themes related to socio-political dynamics informed by the study of violence. Fragmented, but highly aestheticised body parts, become thus symbols, signifiers, that stand for more complex streams of thought that they might look at a first sight reading.

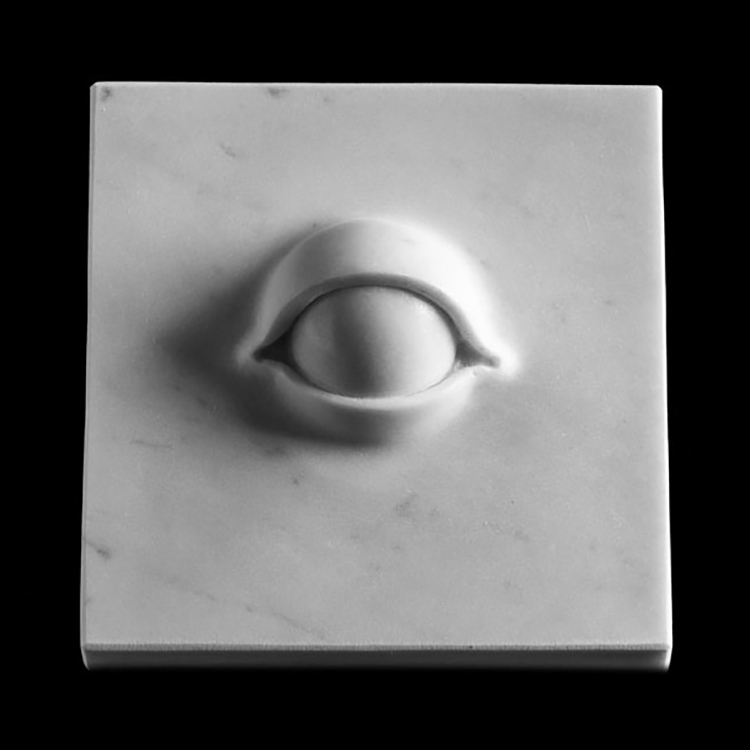

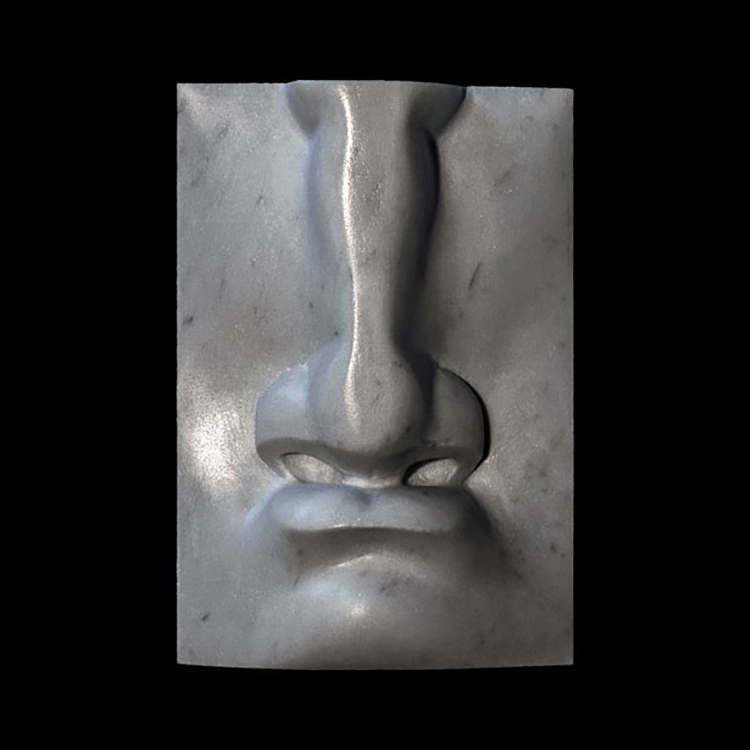

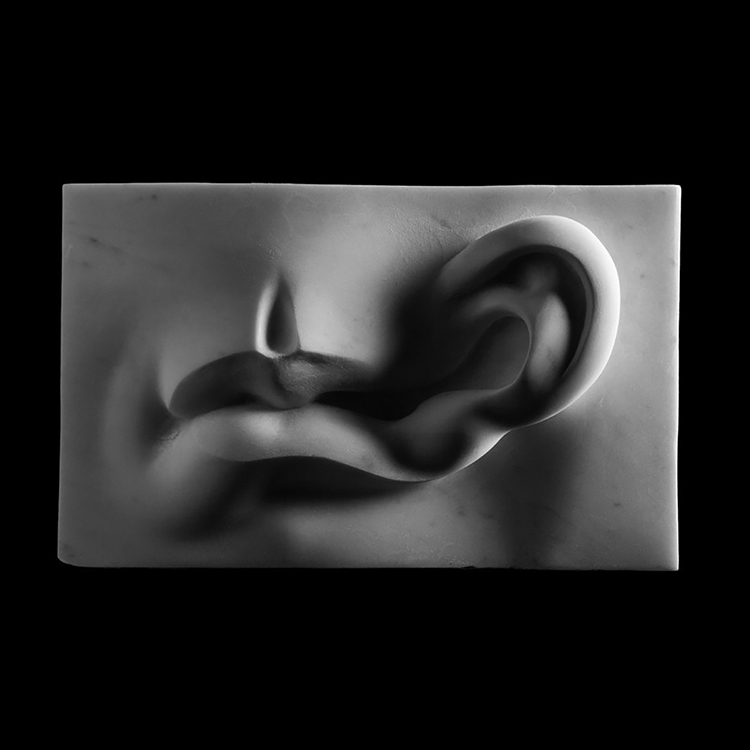

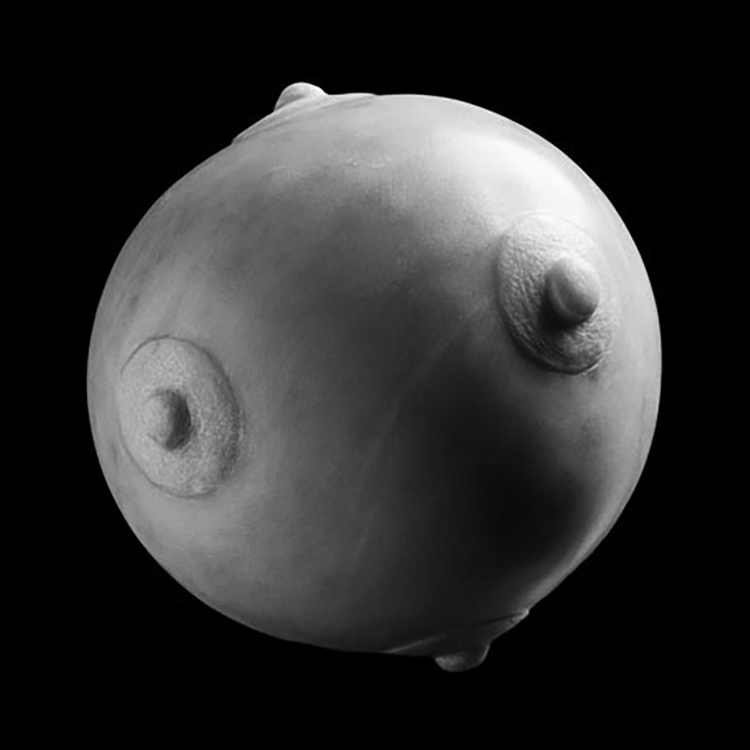

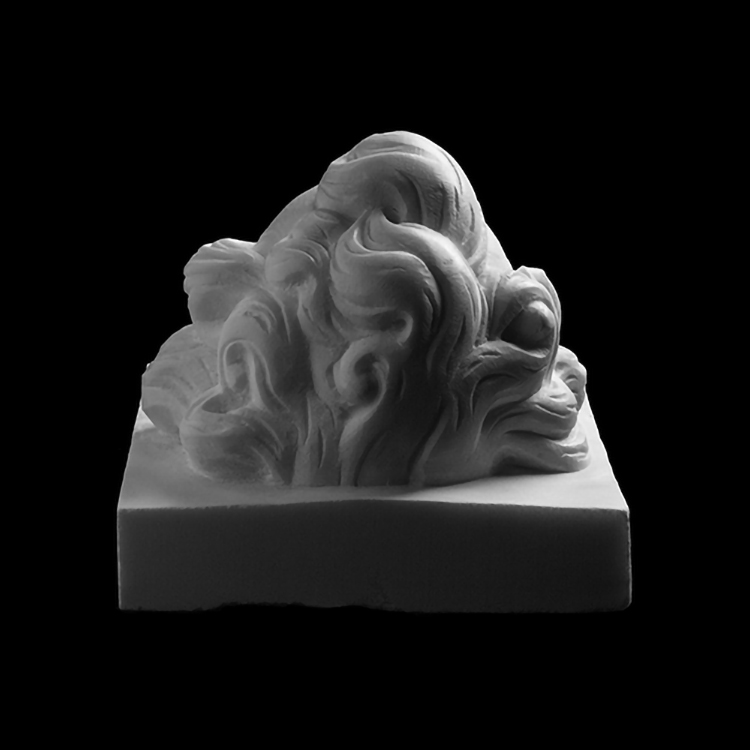

In my case, I will present 18 small marble works divided into several series. The first series consists of eight ex-voto’s, votive offerings in the shape of human body parts. In ancient times, such representations were gifted to various divinities to ask for the healing of a specific body part. A practice that reveals the dominating power apparatus inherent to society and its beliefs.

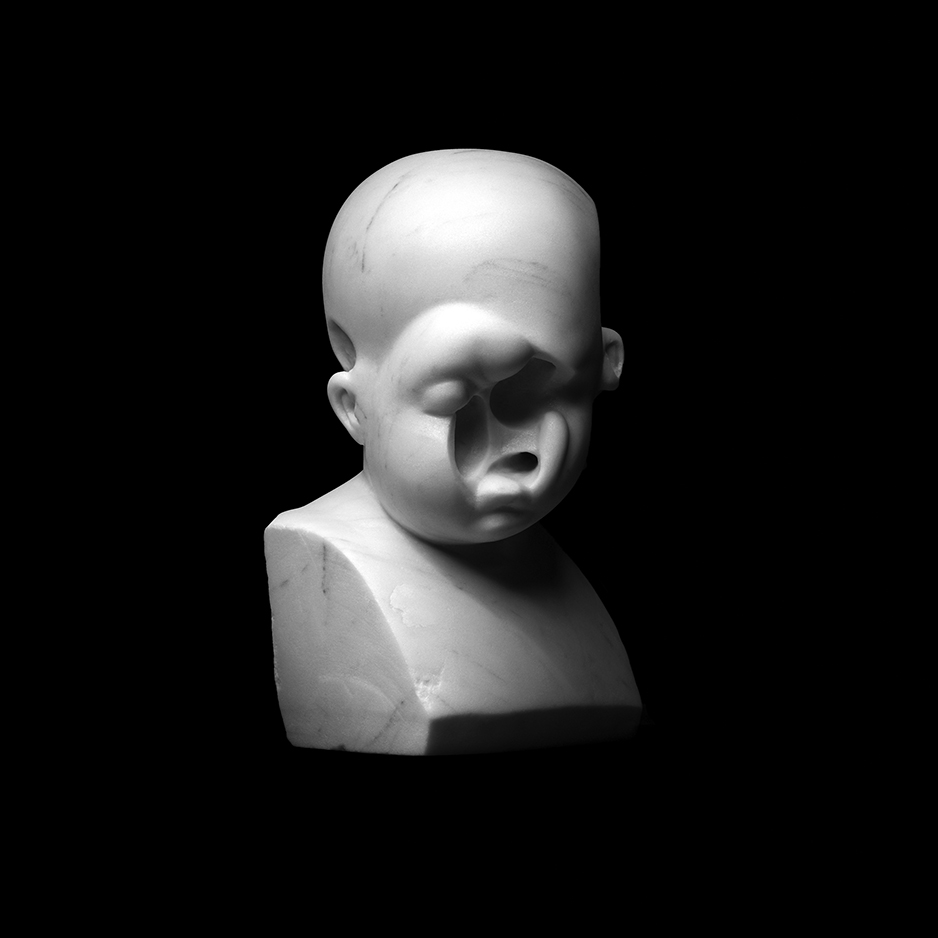

The ancient custom, to which the contemporary practice of lighting candles in a sanctuary can be traced back, allows me to maintain a link with the traditional depiction of the human body while (literally) detaching a specific part from its original context to address other topics. Another series consists of “defaced” children’s heads. The deletion of all the facial features removes the identity of the portrayed subject, precluding any attempts of recognition. While referencing to general iconoclastic practices, it also confronts the now customary habit of censoring children’s faces on the web to prevent their abuse. Thus alluding to what extent the fear of catastrophic scenarios has entered and commands our daily life.

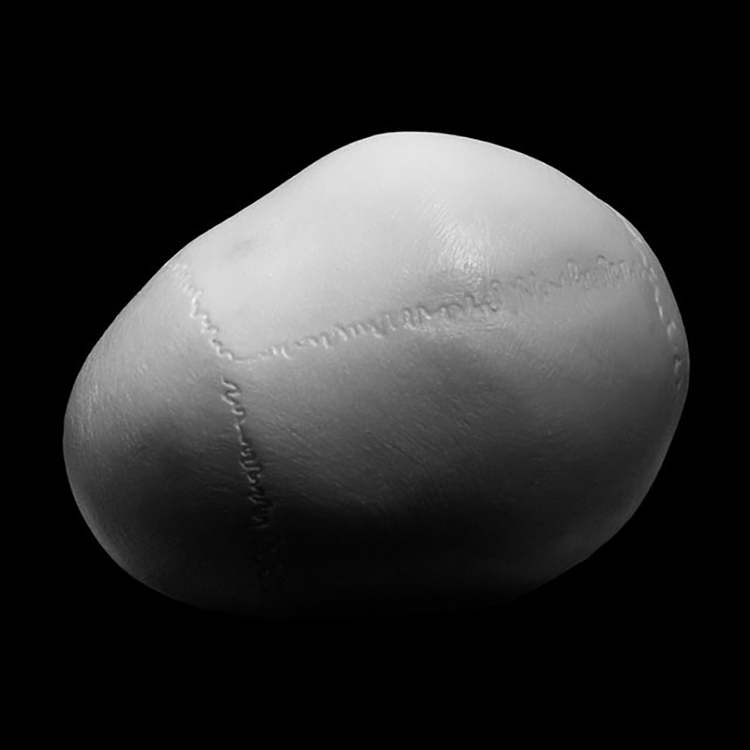

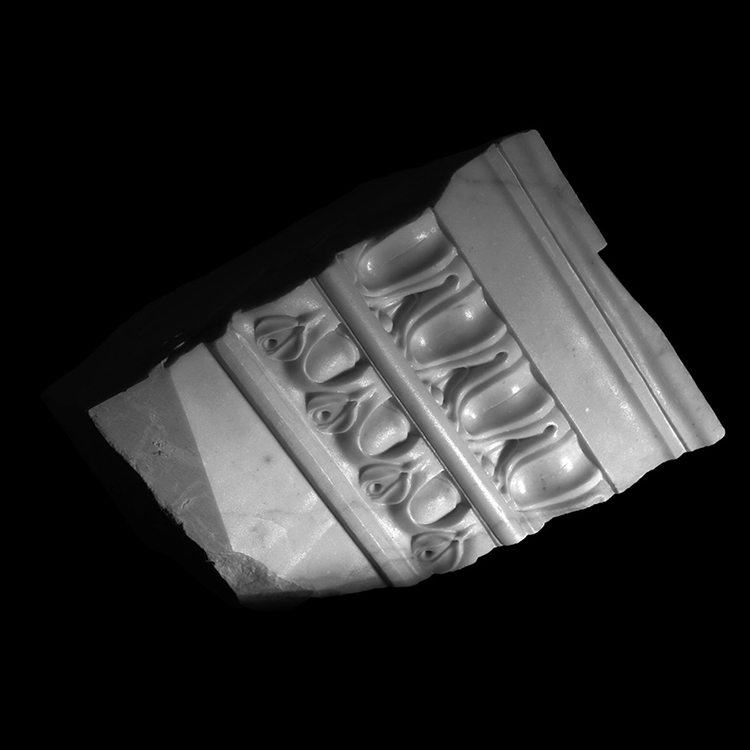

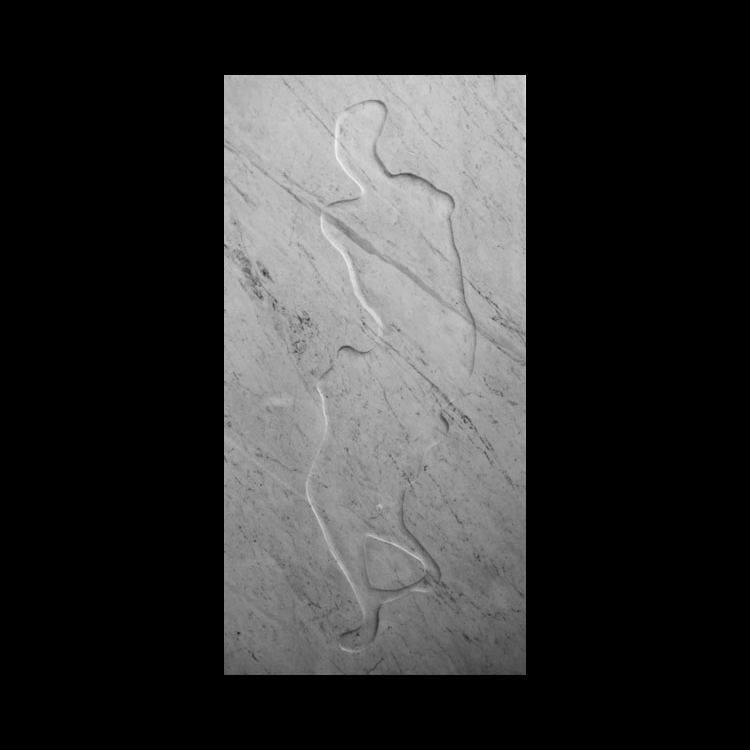

I recently developed, and interest in calligraphy and letter carving and translated this into a series of stone inscriptions. One is a modified quote from the second Psalm. It is cut in Roman capitals, the character that is usually associated with imperial authority, and it reads Servite in Timore, Exultate cum Tremore”. (Serve in fear, rejoice in tremor). I omitted the word “Deo” (God) to point to the systemic violence driven by fear that underlies more general politics of power. Another inscription reads “Enbide Calco Te” (Envy, I tread on you). It is displayed on the floor of the gallery, like a doormat, and visitors can literally walk on it, thus (very slowly) reshaping the stone with their action and eventually cancelling the message.

The rest is a surprise. Come and see for yourself.

Share article