Stone Talk

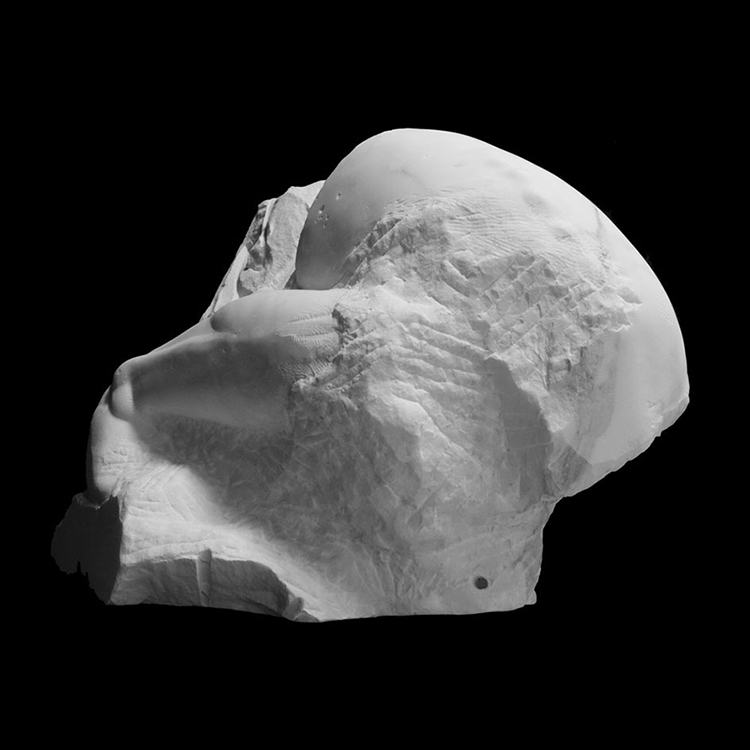

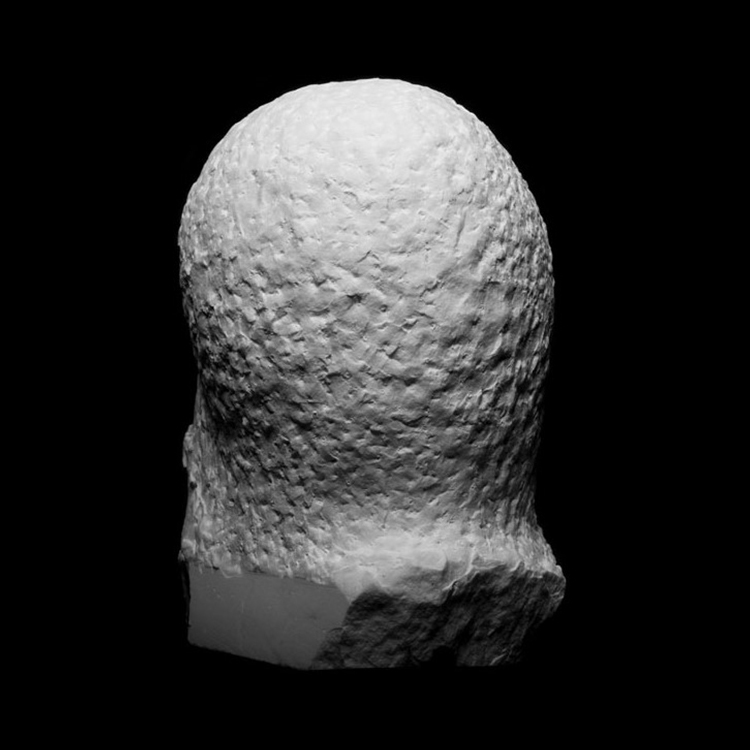

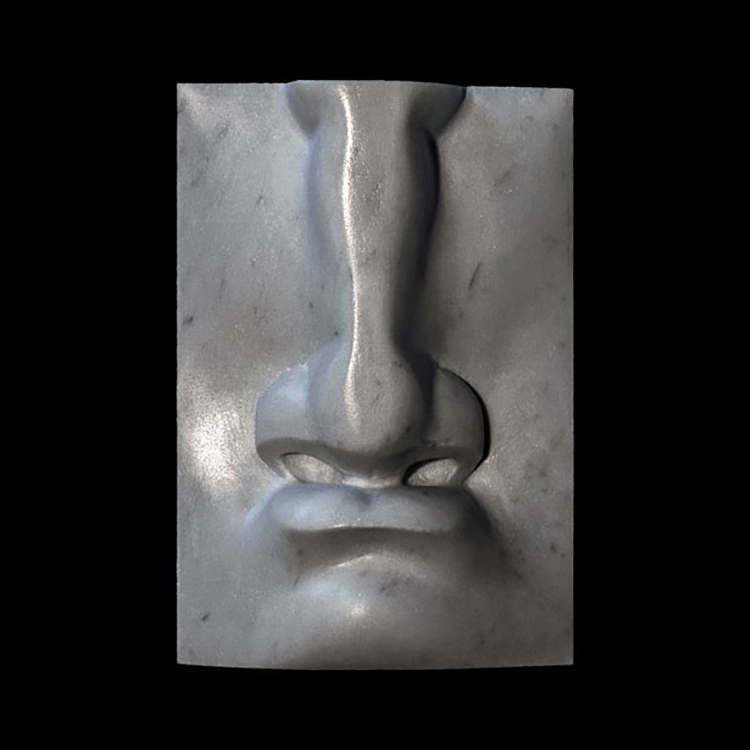

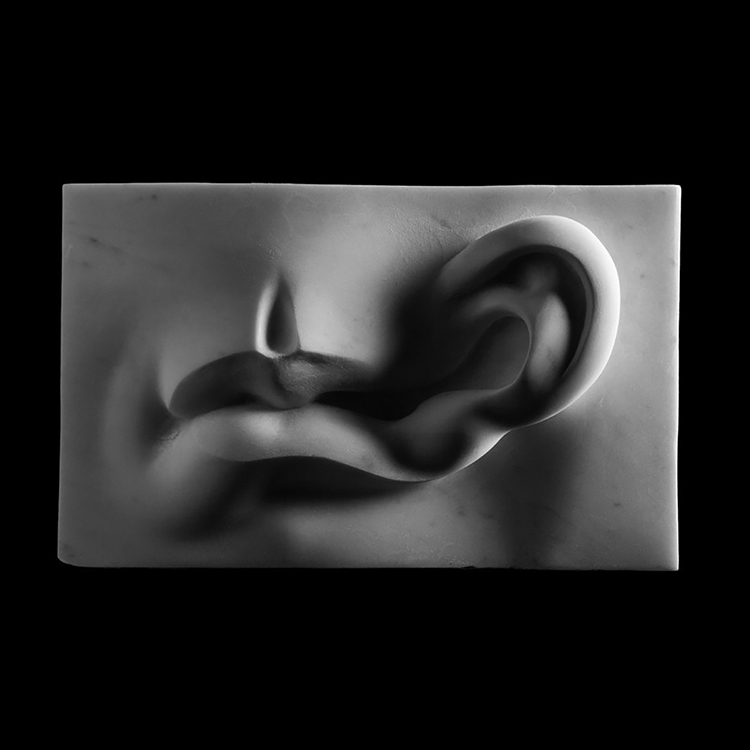

by Athar Jaber | 22 December 2024

Essay — The Legacy and Impact of Interactive (Stone) Sculptures in the Public Realm

From a panel talk I gave at the 1st Dubai Sculpture Symposium on 14 December 2024.

The Enduring Power of Interactive Sculpture

The term ‘interactive sculpture’ is usually associated with contemporary artworks that react to the presence of the viewer, usually through technology or participatory elements. These works often rely on sensory triggers like sound, light, or movement, captivating audiences through their dynamics and novelty. However, as technology evolves, these sculptures risk becoming outdated, and their initial allure fading into obsolescence.

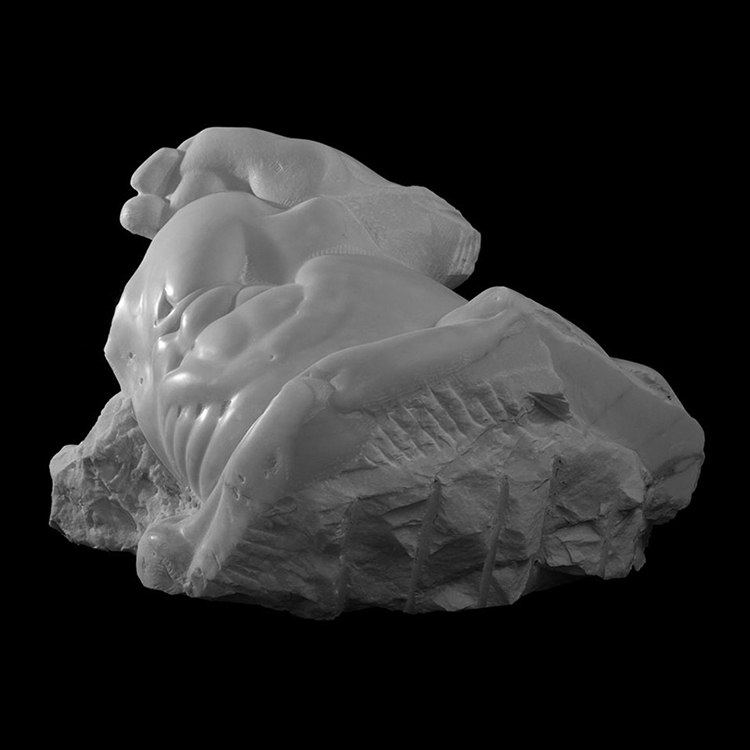

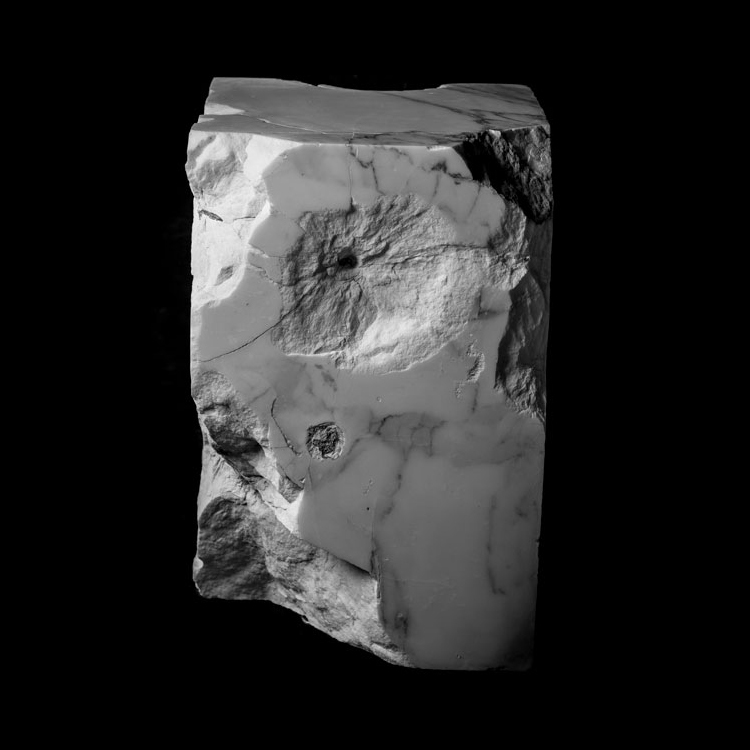

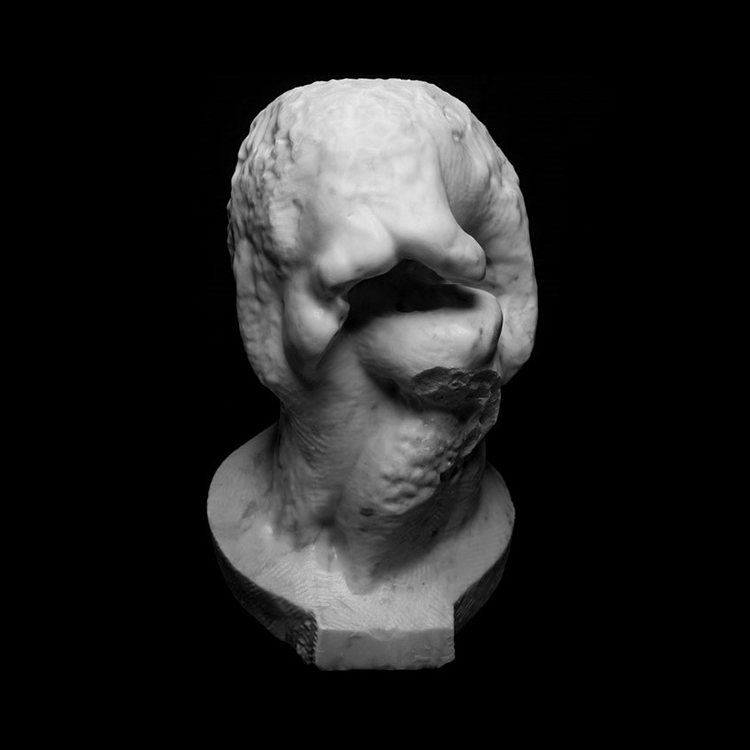

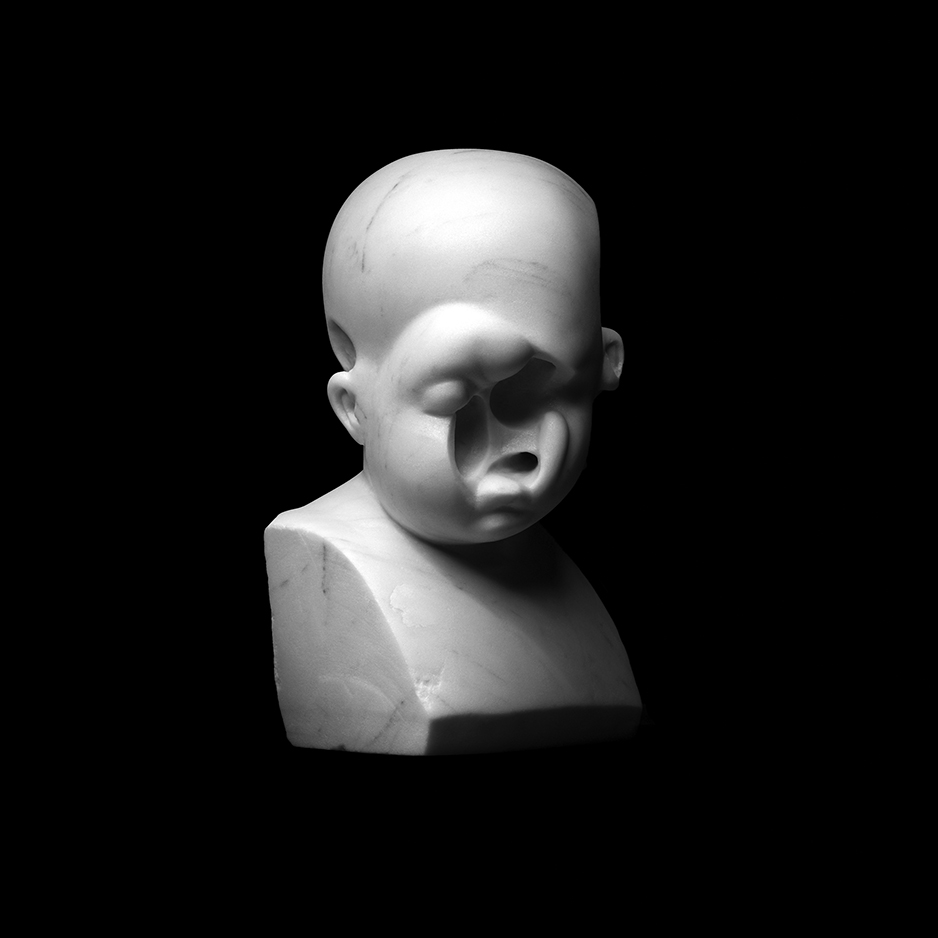

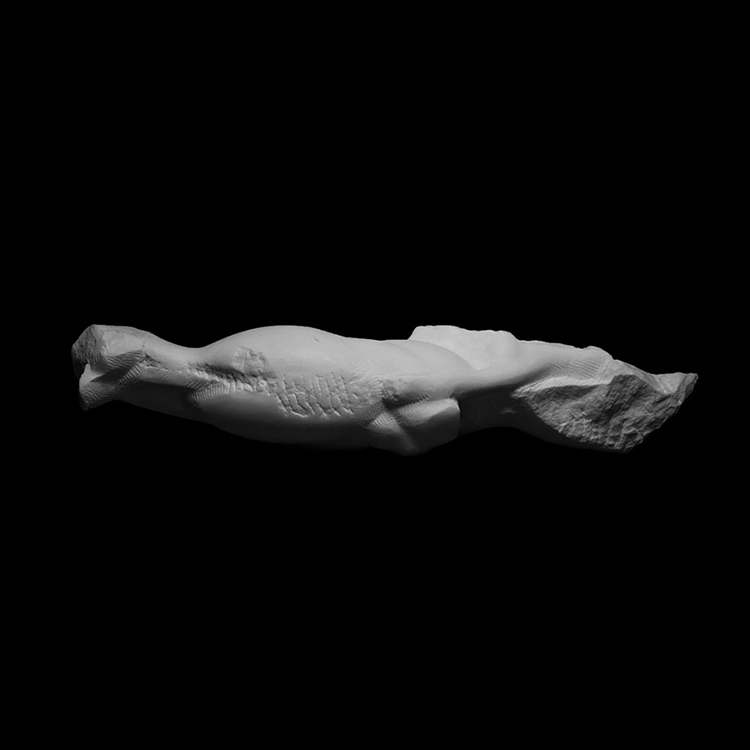

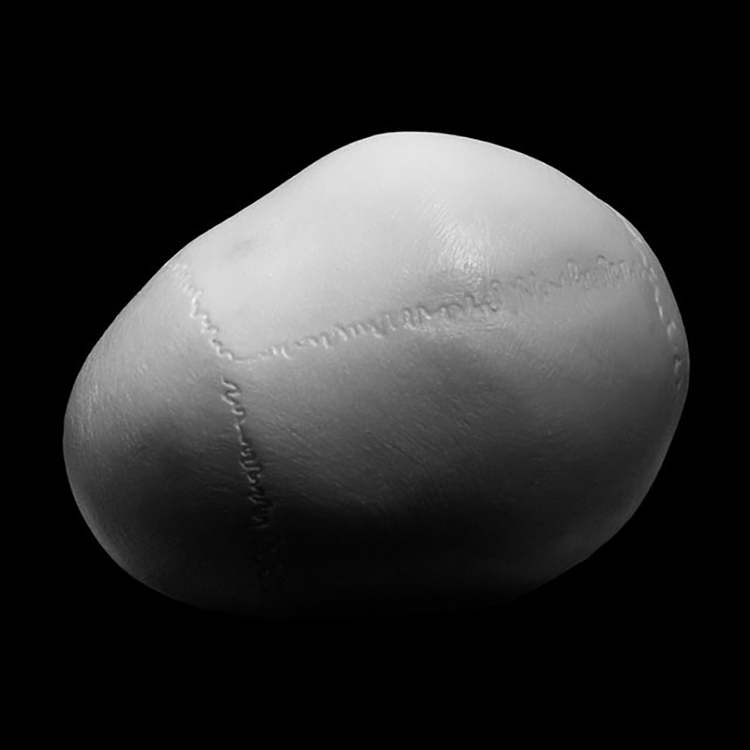

In contrast, stone sculpture represents an enduring form of interactivity that is subtler yet profoundly impactful. While stone does not offer the immediate dynamism of its high-tech counterparts, it invites a deeper kind of engagement—one that unfolds emotionally and intellectually, often inspiring a spiritual connection. The timeless quality of stone demands a slower, more reflective interaction, encouraging viewers to contemplate the weight of history and the permanence of the material.

The Historical Roots of Interactive Sculpture

Sculpture has always been interactive, even if it was not explicitly referred to as such. Throughout history, sculptures have played a central role in human society, serving as visual representations of powers—natural, spiritual, or political—that were believed to govern the world. In fact, the term ‘monument’ stems from the Latin monere, meaning ‘to admonish,’ underscoring the role of these structures in reminding communities of the higher powers they revered.

In their role as visual representations of these authorities, sculptures became recipients of active engagement from communities. They were worshipped and cared for; offerings such as gifts, food, or oils were regularly presented to them. This interaction was rooted in the belief that these acts could invoke divine favor, bringing healing, good harvests, or protection. Far from ephemeral entertainment, the interaction between sculpture and society was deeply consequential, reinforcing the relationship between humans and the forces they revered.

Until relatively recently, sculptures were primarily intended to be engaged frontally. They were often placed against walls or in niches, creating a visual hierarchy that encouraged viewers to connect with them as if they were royalty—respectfully, reverently, and from a distance. This static relationship between the viewer and the sculpture persisted for centuries.

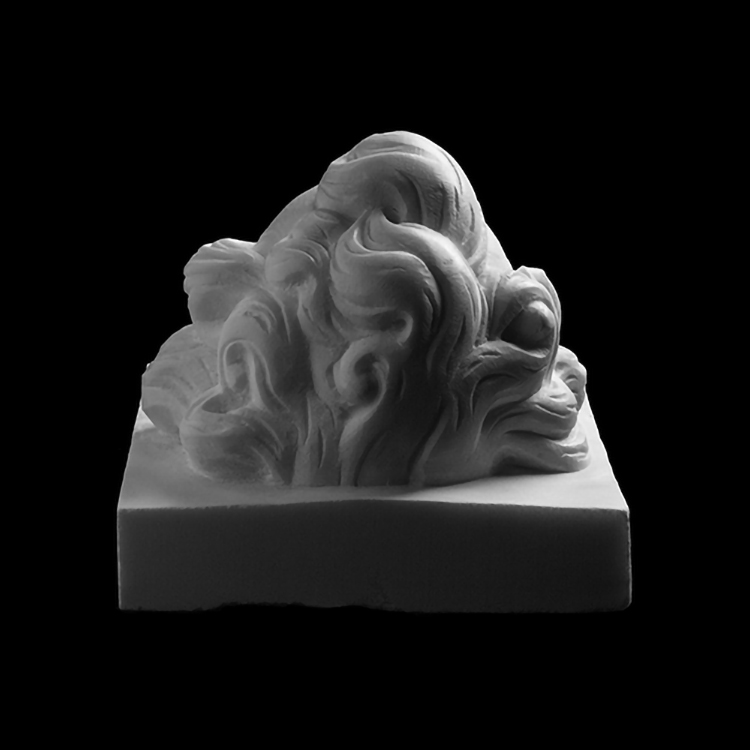

The Late Renaissance introduced a pivotal shift in how sculptures were designed and experienced. Pioneer sculptors developed a compositional technique known as figura serpentinata, in which the multiple figures within a sculptural composition would each face different directions. These dynamic arrangements prompted viewers to walk around the sculpture, experiencing it from various angles. Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine (1582) is a striking example of this technique. This monumental marble sculpture features a spiraling composition of three interlocking figures, compelling the viewer to move around it to grasp their dramatic interplay. Often placed in the center of palace courtyards, such works invited motion, transforming the act of viewing into a participatory experience. For the first time, the viewer’s movement became an integral part of the sculpture’s meaning, adding a novel dynamic aspect to the interaction.

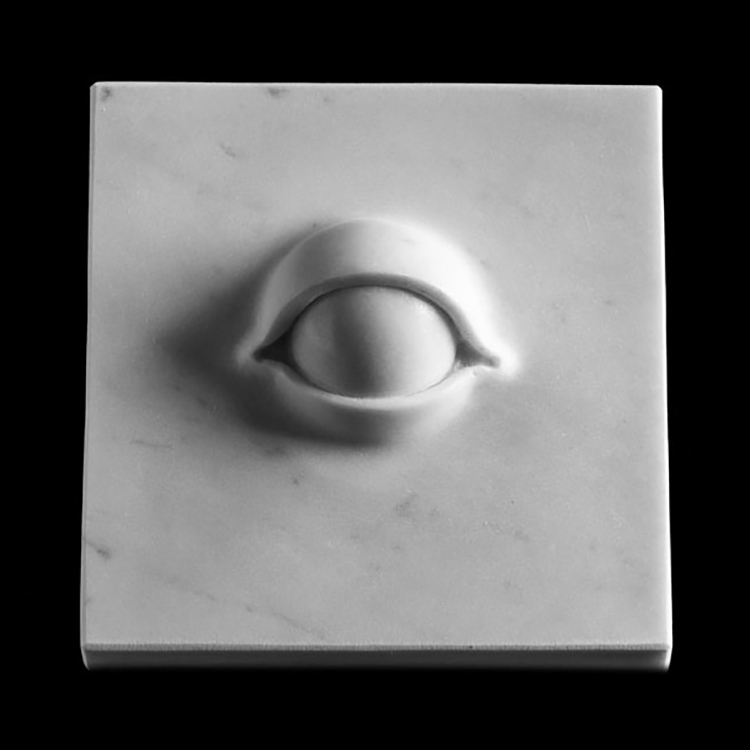

This dynamic, circular movement of interaction is not confined to art alone. In Mecca, pilgrims engage in a circular wandering around the Kaaba. This spiraling circumambulation culminates at the Black Stone embedded in one of the Kaaba’s corners, where pilgrims touch, kiss, and bless the sacred stone in acts of profound devotion. Here, the physical act of movement is inseparable from the emotional and spiritual transformation it inspires—a perfect illustration of how something can “move” us both physically and spiritually.

Other sacred stones across the world offer similar examples of interactive engagement for various faiths. The Stone of Anointing in Jerusalem invites worshippers to kneel, pray, kiss it, rub oils onto it, or press garments against it in acts of reverence. At the Wailing Wall, also in Jerusalem, individuals place their heads against the stone to pray or leave written prayers in its crevices, embedding personal hopes and connections into the material itself.

In other religions, stones become the recipient of offerings such as milk, blood, oils, flowers, and edibles during rituals, symbolizing a profound connection between the material and the divine. These examples highlight how sacred stones transcend their physicality to become vessels for collective faith and spiritual interaction.

These examples demonstrate that sculptures and other stone artifacts’ purpose has rarely been limited to passive viewing. Interactivity has always been an intrinsic aspect of sculpture. Whether experienced through physical movement or spiritual engagement, sculptures have consistently invited interaction, reminding us that their power lies not only in their materiality but in the connections they inspire.

Community Engagement Through Sculpture

As shown above, interactive sculptures have the ability to transform public spaces into shared spaces where communities come together. Whether playful, poetic, or introspective, their true power lies in their capacity to unite people from diverse backgrounds. These works create focal points for gatherings, celebrations, and moments of reflection. By inviting participation and inspiring a sense of belonging, they enrich the shared experiences of those who encounter them, fostering pride and strengthening the bonds that hold communities together.

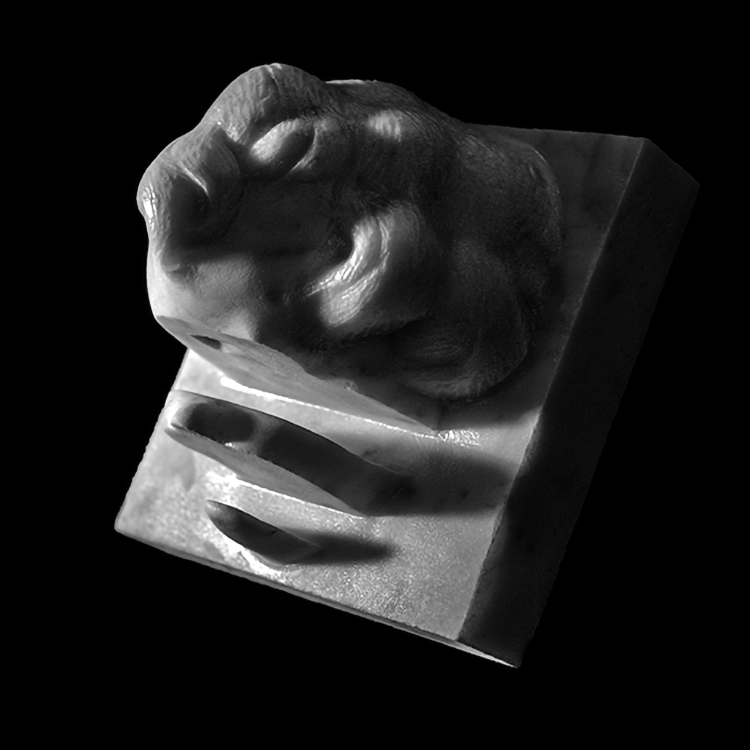

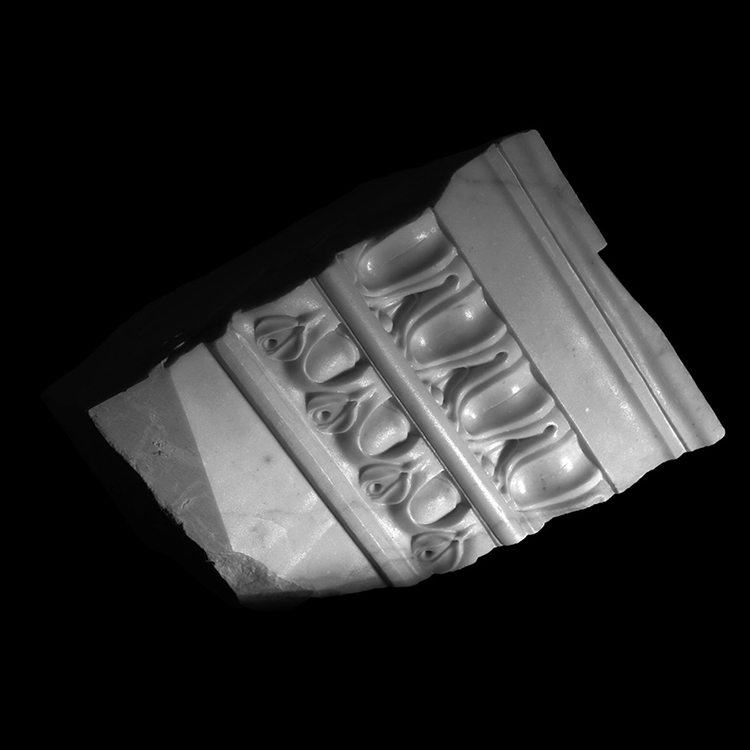

I experienced this firsthand growing up in Florence, Italy. Though I was not an Italian citizen, I felt deeply connected to the city and its artistic heritage. I vividly remember spending hours under the Loggia dei Lanzi, sketching the sculptures it houses. I would run my fingers along the intricate reliefs on the marble pedestal of Cellini’s Perseus, captivated by its details and craftsmanship. As I traced the stone, I often thought of the countless others who had touched it before me, feeling a connection to past generations that seemed to transcend time.

These monuments and my interactions with them planted the seeds of belonging to a city whose beauty shaped not only my identity but also that of Florence itself. Their stories, carved in stone, have long been intertwined with the city’s narrative, inspiring pride and connection across generations. Remarkably, this legacy stems from commitments made by Florence’s cultural players over 600 years ago—a testament to the enduring impact of public art.

Florence’s artistic heritage demonstrates that investing in meaningful and accessible public art enriches communities not only in the present but for generations to come. These works transform cities into living histories, fostering connections that make citizens active participants in their cultural narrative. This legacy reminds us that today’s cultural leaders have the opportunity to create similar enduring contributions by championing thoughtful public monuments that reflect and strengthen the identity of their communities.

Conclusion

The enduring legacies of public monuments show us that the power of sculpture lies not only in its ability to adorn spaces but also in its capacity to engage, connect, and transform. Interactivity—whether through physical movement, emotional resonance, or cultural meaning—is what breathes life into these works, allowing them to remain relevant and impactful across generations.

Interactive sculptures are far more than objects defined by superficial movement or sensory triggers; While some works may rely on sound, motion, or light to captivate viewers, the true essence of interactivity lies in deeper, more lasting exchanges. These sculptures engage the intellect and emotions, shape cultural identities, and foster collective meaning. Crucially, this interaction is reciprocal: just as sculptures act on their audiences, audiences in turn imbue them with layers of memory and interpretation, ensuring their continued relevance and meaningful endurance in time.

Thank you for your time.

Athar

Join the talk

On Sundays, at irregular intervals, I send out Stone Talk, a newsletter where you’ll find tips and recommendations on things I believe are worth watching, listening, reading, visiting or exploring. All related to (stone) sculpture and stone carving. And sometimes I use the space to put down my thoughts on specific—stone carving related—topics.

The newsletter is also a great way to stay updated with my artistic activities such as exhibitions, new works, limited editions, publications, as well as my educational activities such as courses, workshops, lectures, tutorials and much more.

If you wish to subscribe to Stone Talk, please fill in the form.