Sculpture is Slow

Interview with Andrea Guastella for ArtsLife | 13 January 2025

“In an increasingly frenetic world dominated by digital stimuli, sculpture offers a pause—a moment for deep reflection and a direct connection with materiality. It doesn’t compete with immersive technologies or interactive installations but provides a counterbalance: an intimate and meditative experience.” We discuss this with Athar Jaber in the thirty-ninth episode of Project (S)culture.

Andrea Guastella: When did you and sculpture first meet?

Athar Jaber: I was born in Rome, in an artistic environment: my parents, uncles, and all their friends were painters. In the ’80s and ’90s, my father was one of the painters in Piazza Navona. I recall summers spent in the piazzas and alleys of Rome, waiting for him to finish work. On those evenings, I mentally played with the city’s sculptures. In the 1990s, after moving to Florence and being influenced by my artistic surroundings, I began drawing regularly. When I grew bored of copying figures from art history books, I wandered the city, sketching Florence’s statues live. I spent entire days under the Loggia dei Lanzi, in Piazza della Signoria, at Orsanmichele, the Uffizi Gallery, and the Accademia Gallery, drawing the sculptures that adorned the city. That was my first true and conscious encounter with sculpture—a moment that profoundly marked my artistic path. However, the decisive turning point came years later when I first touched a block of stone with hammer and chisel during my studies.

AG: Where did you study?

AJ: Honestly, I think my most profound and visceral education happened during my youth in Italy, as described earlier. My formal academic training, however, took place at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. There, I learned the classical techniques of sculpture and developed an approach that bridges tradition and contemporaneity. During those years, I not only honed technical skills but also explored sculpture as a medium to address contemporary themes, combining material knowledge with openness to new aesthetics and interpretations.

AG: From Italy to Belgium to the Middle East, you’ve often changed your home and workplace. Wh?

AJ: Actually, the correct sequence is Italy, Yemen, Russia, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and finally, for just over a year, the UAE. These moves were driven by socio-economic circumstances experienced by my mother, who had to emigrate in search of better opportunities. Living in such diverse cultures has been a gift, allowing me to develop a unique sensitivity to themes like identity, belonging, and transformation. In my late teens, we moved to the Netherlands, and when I decided to study sculpture, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, nearby in Belgium, was the best available option. After completing my studies in 2008, I taught at the same academy for fifteen years, consolidating my skills as a sculptor and teacher. In 2023, dissatisfied with the local reality and seeking new artistic opportunities, I moved to Abu Dhabi—and I couldn’t be happier.

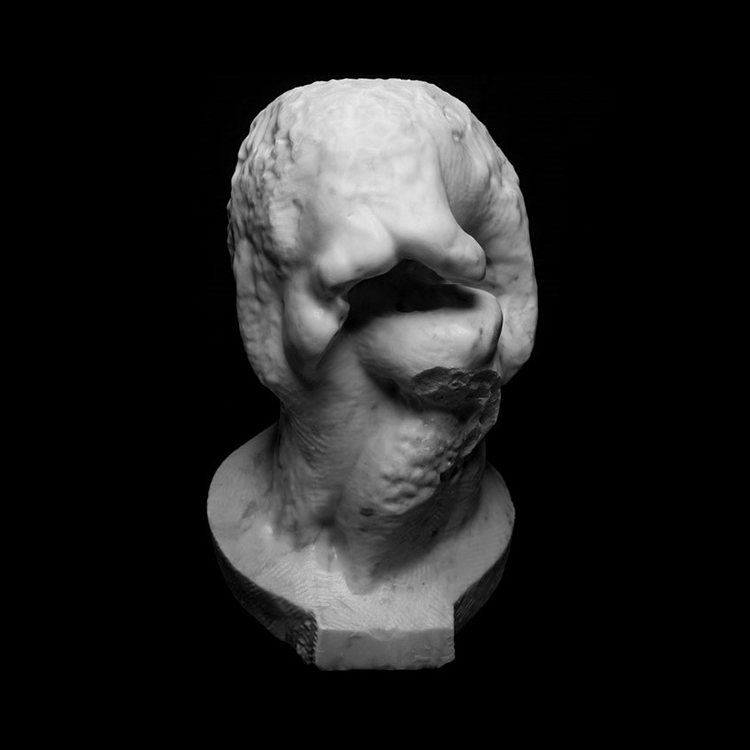

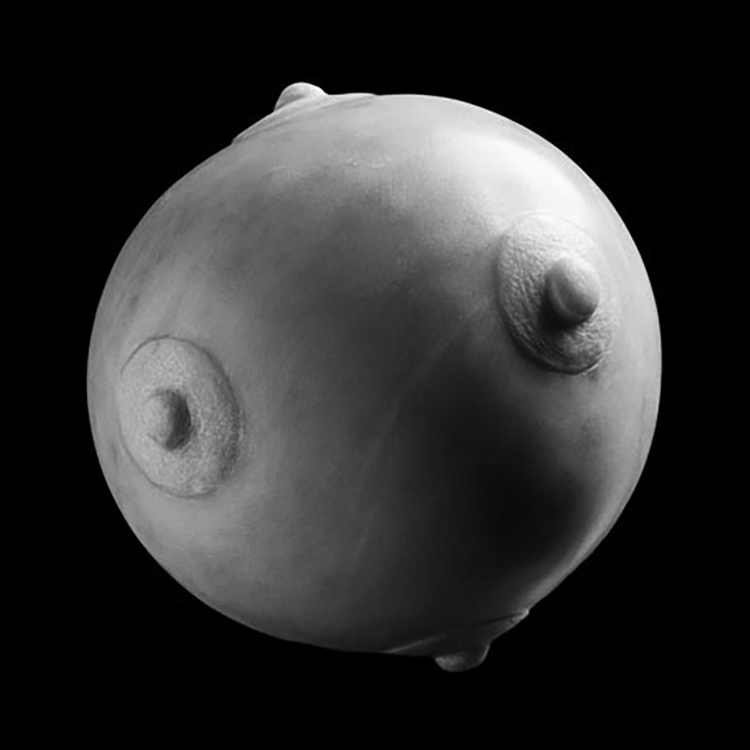

AG: The Greeks believed art was born from thauma—awe, bordering on terror. In your case, this awe often manifests as breaking or fragmenting your own works. Where do you think this form of expression originates?

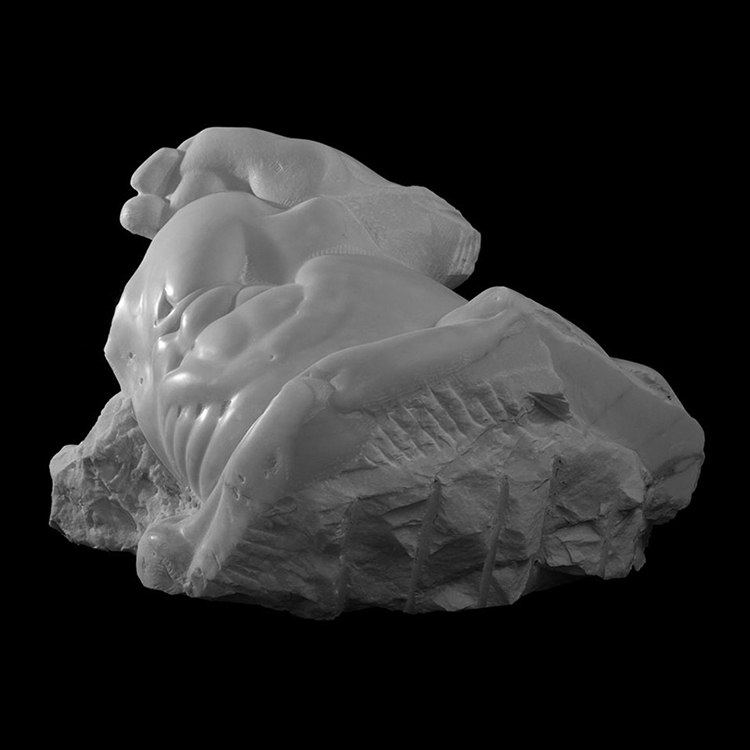

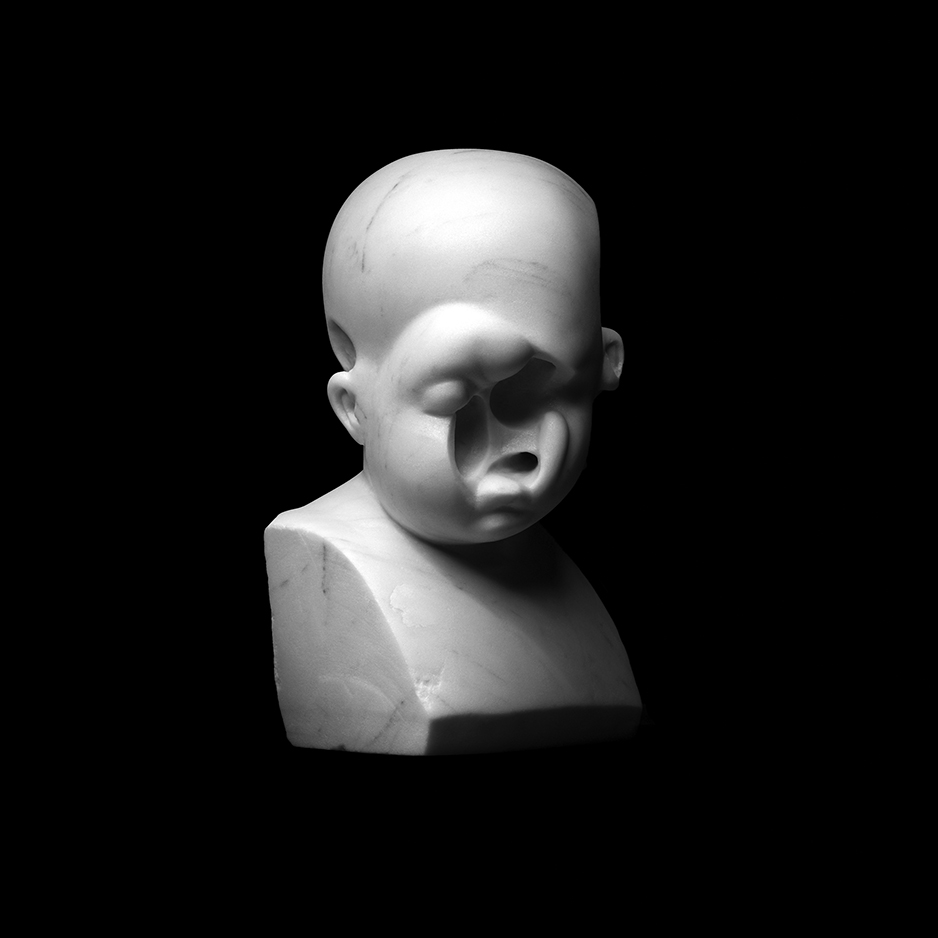

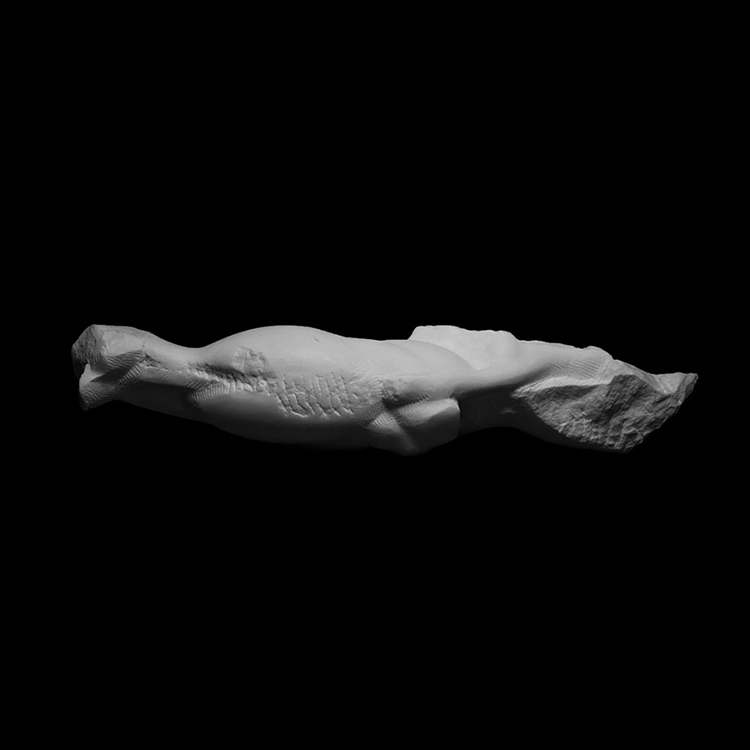

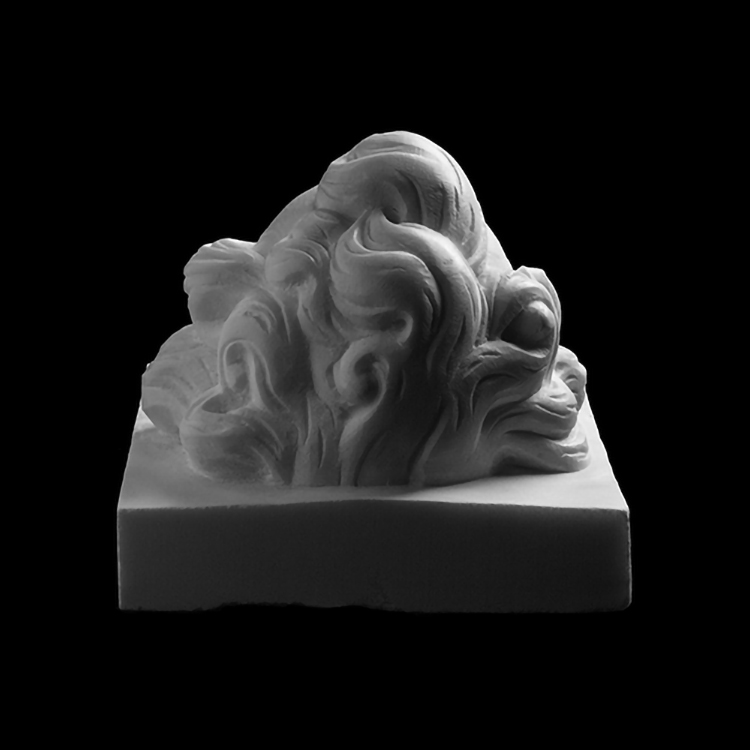

AJ: Growing up in Florence, one of the most beautiful cities in the world, immersed me in almost inconceivable beauty and harmony. At the same time, being of Iraqi origin, during the 1990 Gulf War, I woke up every morning to images of bombings in Iraq. These images of destruction—dismembered bodies, destroyed homes, shattered lives—coexisted with the aesthetic perfection of Renaissance works I encountered daily. I couldn’t reconcile how humanity could create such beauty and simultaneously such destruction. This tension—between creation and destruction, preservation and loss, integrity and fragmentation—permeates my work. Through it, I continually confront entropy and our futile attempts to preserve the fragility of inherently precarious beauty.

AG: A recognized model of this paroxysmal tension is Michelangelo. Do you find similar strength in contemporary artists? Who do you feel closest to?

AJ: Michelangelo is an inevitable reference for anyone working in sculpture. However, the works of his that resonate most with me aren’t the perfectly completed ones—like David or the Pietà of St. Peter—but the unfinished ones: the Prisoners, his later Pietà. I appreciate them aesthetically but also conceptually because they touch on themes I hold dear. Among contemporaries, I see similar strength in artists like Francis Bacon, who captures the human condition with unique emotional rawness. Anselm Kiefer, with his work on memory and destruction, conveys a sense of monumental fragility. I feel close to those who use material as a medium to tell the human condition authentically.

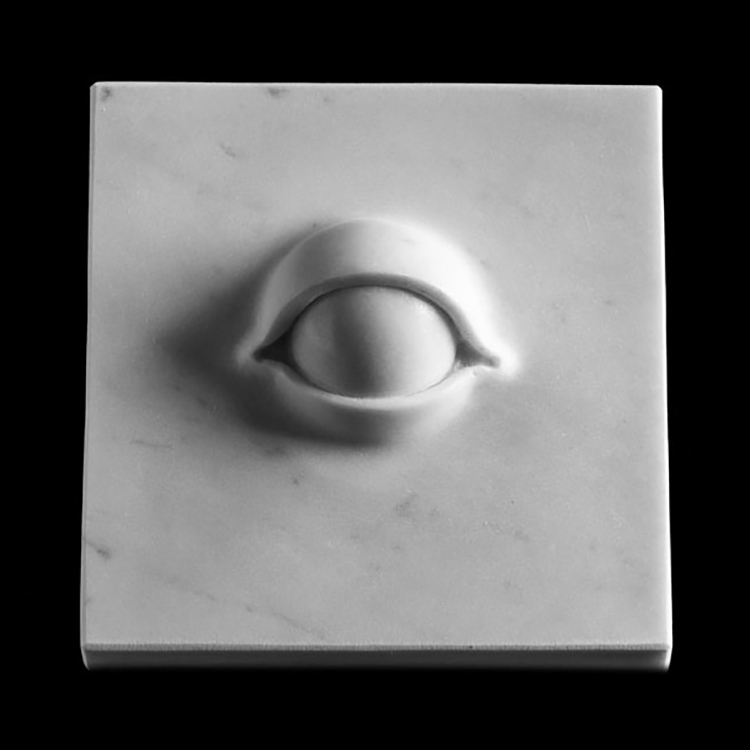

AG: Michelangelo serves as both a bridge between past and present and a model of figuration that opens to abstraction. Do you think sculpture remains comprehensible in a world accustomed to different stimuli?

AJ: Sculpture assumes an essential role precisely because it offers a tangible and physical experience missing in the virtual. In an increasingly fast-paced world dominated by digital stimuli, sculpture is a pause for deep reflection and direct connection with materiality. It doesn’t compete with immersive technologies or interactive installations but provides a counterweight: an intimate, meditative experience. Sculpture is slow; it takes time to create and appreciate. It requires silent observation, attention, and space for thought and contemplation. Unfortunately, not everyone—artists and spectators alike—can dedicate such attention to a static work of art anymore. But therein lies its strength: in offering an alternative and reminding us of the value of time and presence.

AG: Could you describe your working method, from the idea to the first sketch and final realization?

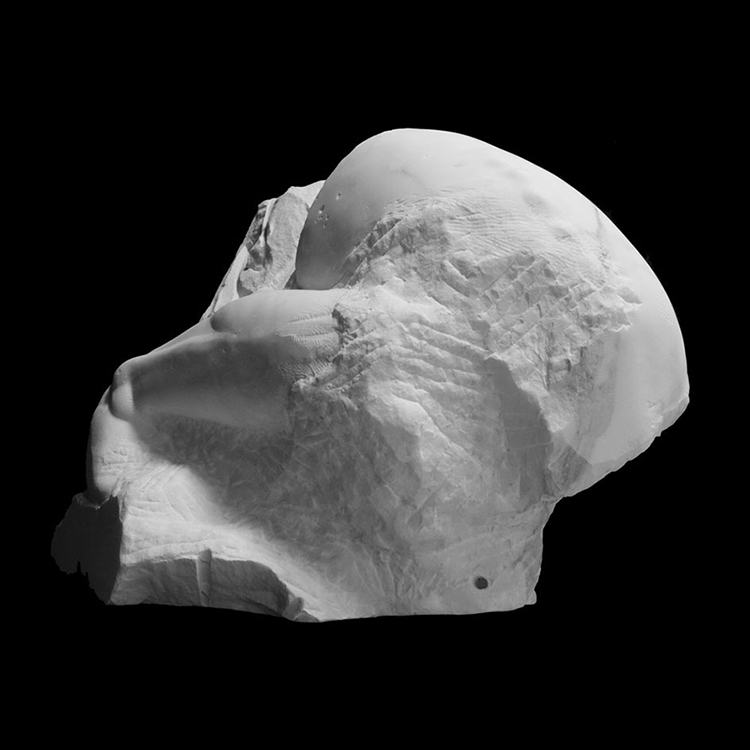

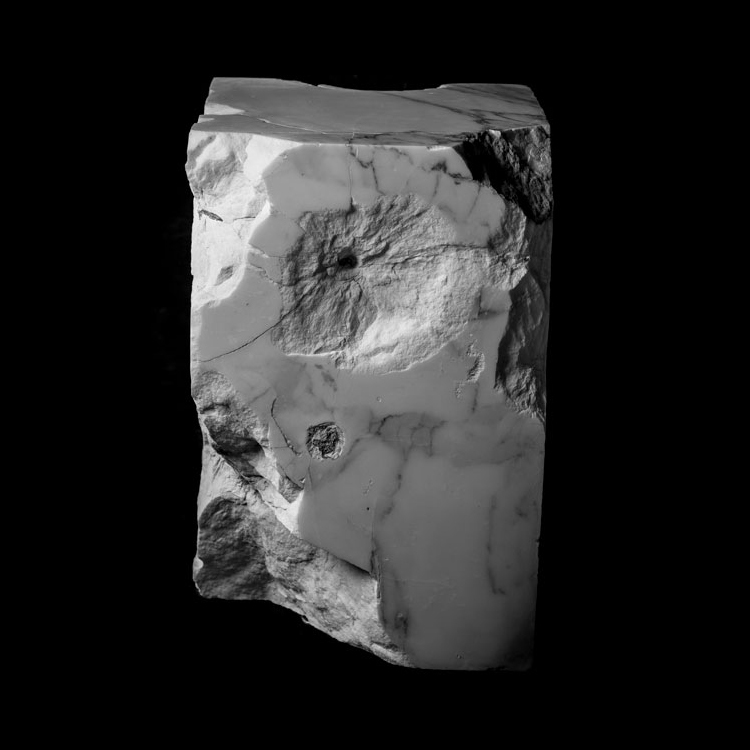

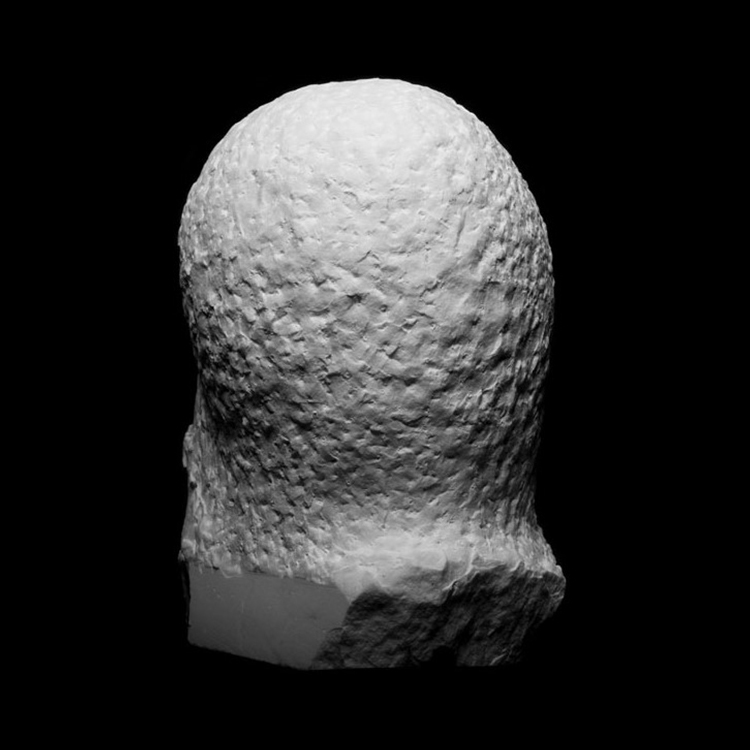

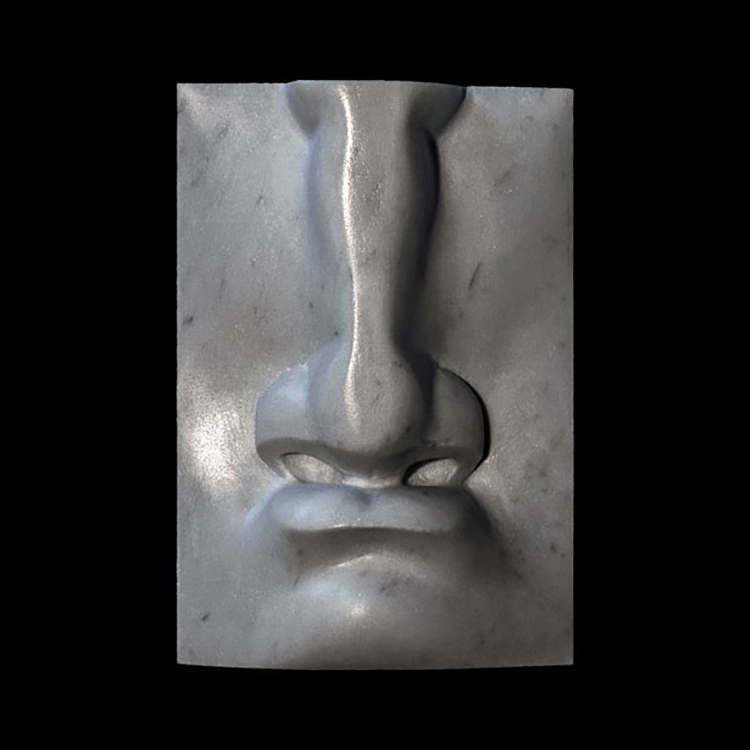

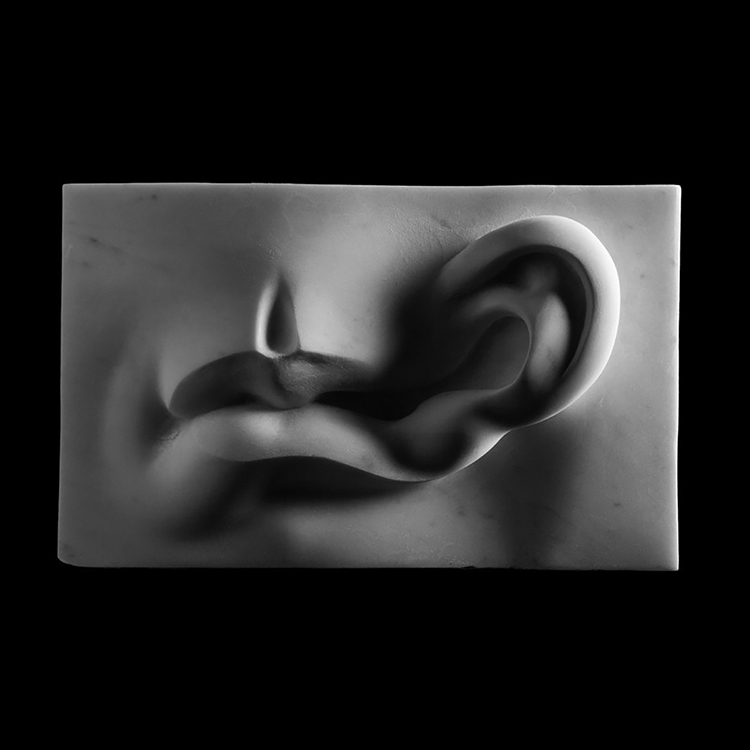

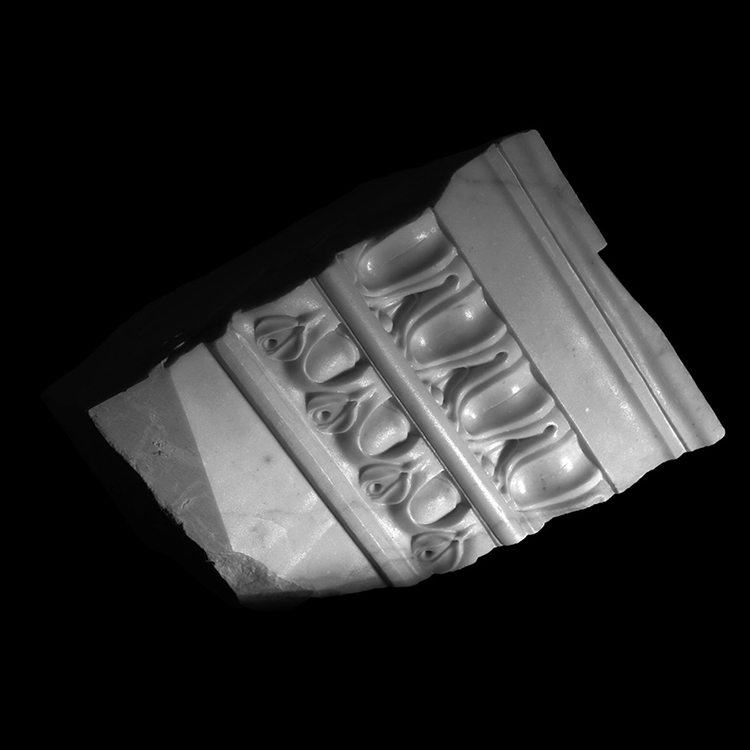

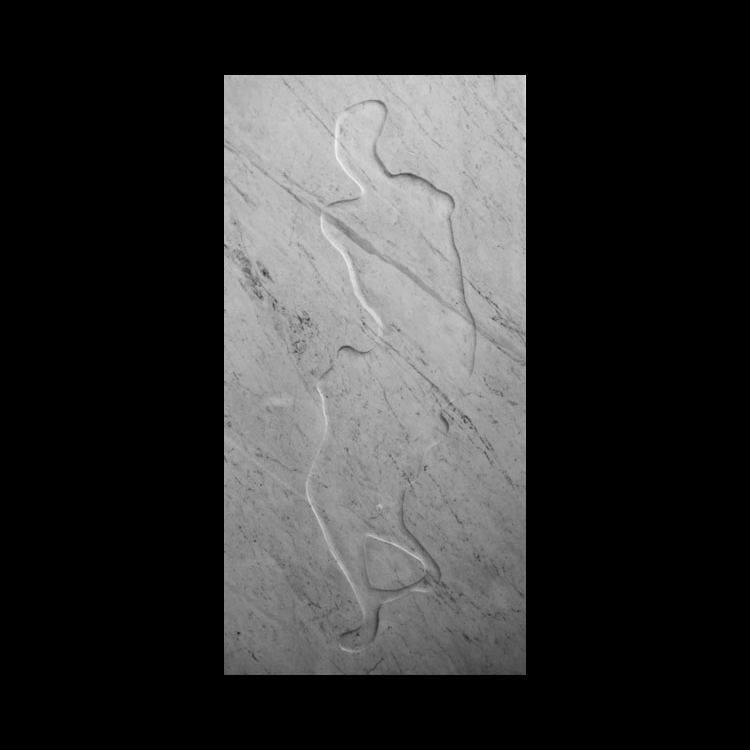

AJ: The concept is always the starting point. Everything begins with an idea, often sparked by reflections on society. Each project is unique, and the design and realization vary accordingly. For figurative sculptures, I work directly on the marble block without preliminary drawings or models. This approach allows me to be guided by the stone itself, establishing a continuous and spontaneous dialogue with the material. Each piece is an improvisation, where the unexpected becomes an integral part of the creative process. I know the direction I want to go—whether it’s a bust, a torso, or a figure—but I don’t have a predefined result; the path reveals itself as I go.

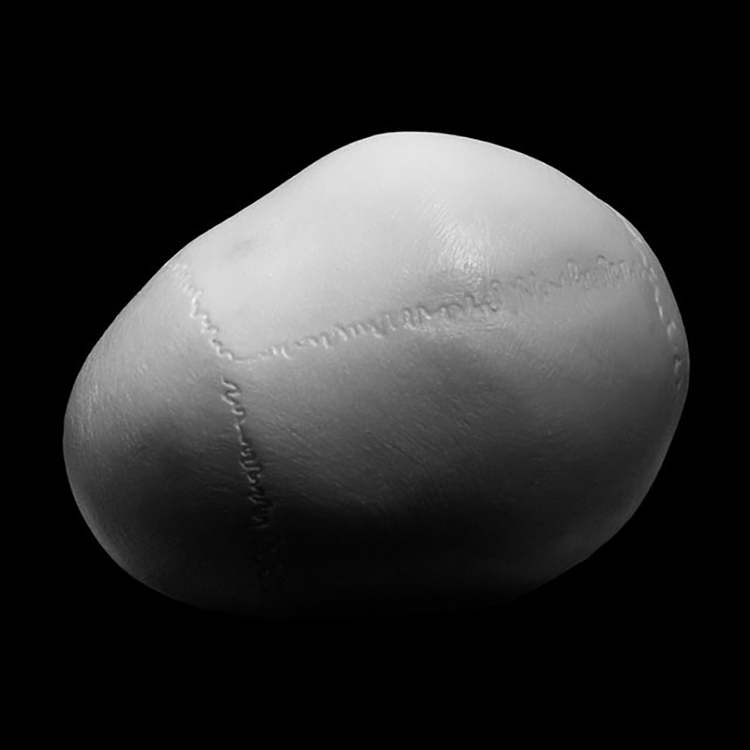

For more conceptual works, such as text-based pieces or public monuments, I adopt a more traditional process. This includes thorough research, preliminary sketches, models, and detailed planning before moving to the final realization. This structured methodology is necessary to ensure the work meets specific criteria tied to the context and meaning I aim to convey.

AG: What do you think about artists who have their works entirely carved by others?

AJ: I believe it’s a personal choice tied to the artist’s vision. Personally, I prefer to carve with my own hands because direct contact with the material is essential to my practice. However, it’s worth remembering that many great sculptors of the past, like Bernini or Canova, used assistants. But those masters possessed a profound understanding of the material and directed every aspect of the work with extraordinary competence. Their assistants worked full-time in a single master’s studio, fully absorbing their aesthetics and finishing techniques.

Today, unfortunately, many artists who commission marble works have no direct experience with the material. This makes them incapable of properly judging the delivered result. Furthermore, the contemporary industry is more production-oriented than quality-focused. Few people today truly recognize the quality of a well-crafted sculpture.

This lack of expertise creates a negative cycle: the worker isn’t incentivized to deliver perfect finishes because they know the client and the institutions they collaborate with cannot appreciate them. Many internationally acclaimed artists, instead of taking responsibility for the public and history, focus only on their personal glory and financial gain. The result is a mediocrity that risks becoming the standard.

AG: What about the use of robots in sculpture?

AJ: Robots are interesting tools that can be useful in certain stages of the process, such as roughing, and they offer opportunities for technical exploration. However, their use requires the commissioning artist to be deeply knowledgeable about every aspect of the creative process, from design to planning to programming and execution. This is because designing and programming robots involves highly technical skills distinct from traditional sculpture.

As a result, the gap between the artist and technical assistants, like designers and 3D programmers, becomes even wider, potentially compromising the authenticity of the work. Today, theoretically, anyone could become a “sculptor” with robots: all it takes is a 3D scan of an object, some software modifications, and a press of the “print” button to produce a sculpture. Of course, I’m simplifying—the process is more complex than it seems and often concludes with a hand finish by a skilled craftsman.

But here lies a crucial problem: an artist without a deep understanding of sculptural aesthetics may not be able to judge the final product or properly direct the craftsman. This leads to standardized results and a loss of artistic quality. Just look at the marble sculptures made for internationally renowned artists who are not sculptors: the results are all similar in craftsmanship and finish, and they lack life; they are “dead” objects.

The robotic process often aligns more with design and production than the creation of authentic sculpture. That said, there are exceptions where robots have been used creatively and meaningfully, bringing innovation to sculptural language. However, these exceptions are rare and require a high level of artistic awareness from those who use them. Without this vision, robots risk becoming tools for serial production, stripping sculpture of its deeper essence.

Sculpture, in its essence, is not just a final result but a journey reflecting the dialogue between the artist and the material. The slowness, time, and effort required in the manual process are integral to the work itself. Technology can certainly support the artist but cannot replace the vision, sensitivity, and authenticity that come only from direct engagement with the material. Ultimately, the robot is a tool, but the heart of sculpture always lies in the artist’s intention and hand.

AG: What is your relationship with the unexpected and with mistakes?

AJ: The unexpected and mistakes are essential elements of my creative process. If embraced with an open mind, they can become unique opportunities to discover new ideas and solutions. Personally, I believe that mistakes don’t exist—what we call a “mistake” is simply the unforeseen arrival of an element that wasn’t part of the original plan.

This fear of making mistakes, instilled in us from childhood by authority figures, reflects the state of constant terror and submission we live in. Many great discoveries, from art to science, have been born from mistakes.

I’m often asked, “What happens if you hit the wrong spot? If a larger piece than expected breaks off?” First, you must understand that we are professionals and have developed a sensitivity to our tools that makes mistakes highly unlikely. But even if it happens, it’s nothing irreparable. We adapt and transform the unexpected into a new creative opportunity—just as in life.

AG: How important is criticism to you?

AJ: Throughout art history, so many critics have expressed and continue to express opposing opinions that they cancel each other out. I’m indifferent to it. If someone doesn’t like my work, it means my work isn’t for them—and that’s okay.

AG: You’ve recently moved to the UAE. What differences do you notice between this emerging market, Italy, and Europe?

AJ:The UAE is experiencing a golden age. There’s tremendous enthusiasm for art and a great desire to build a cultural scene. I’ve noticed how, here and now, both public and private cultural agents have the ambition and potential to create an artistic landscape not unlike what was achieved during the Italian Renaissance. I see fertile ground here to experiment and contribute to creating a new regional artistic identity.

AG: In our blood-soaked world, do you think art can influence events in any way?

AJ: Art cannot change the world on its own, but it can change people by offering new perspectives, generating empathy, and opening spaces for dialogue. I believe the artist’s task is to keep creating and let history take its course. Moreover, in a world full of destruction, creating is an act of resistance and hope.

AG: Your most representative work and one you’d like to revisit?

AJ: My early figures. I’m deeply connected to that aesthetic and plan to revisit it on a more monumental scale, exploring new formal and conceptual possibilities.

AG: What are you currently working on, and what will you focus on in the future?

AJ:A month ago, a sculpture of mine was inaugurated in Abu Dhabi during the city’s first Public Art Biennial. This month, my new studio opens—the first traditional stone sculpture studio in the UAE. It’s a historic moment, both for me and the country. In February, I’ll inaugurate my first solo exhibition in the UAE at Ayyam Gallery, one of Dubai’s leading galleries. I’m also working on an important private commission, though I can’t reveal details yet.

Share article